Race

BEING WITHOUT RACE

Find your “original face”

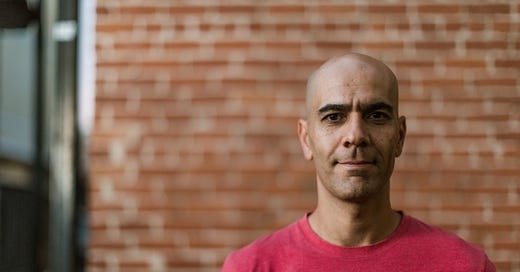

Amir Zaki

“What is your original face before your parents were born?” This is a famous Zen koan attributed to the sixth patriarch, Pinyin Hui-neng.

Another way of putting the question may be, “Who are you?” When one sits with this question intently, countless ideas come and go. The more one sincerely searches, the less one finds. This can be unsettling and also profoundly liberating. What this exposes, undeniably, is that one’s identity is always changing and need not remain rigid nor tied to a language one inherits.

In this essay, there will be no graphs or surveys. You will find no mention of any races that serve to superficially and sloppily label vast swaths of people for the sake of making yet another point about “group disparities,” which, in turn, serve to prop up any number of arguments falling anywhere and everywhere along a political/ideological spectrum. If I may, I’d like to illuminate the topic of identity from a much rarer perspective, looking inward and with a different lens.

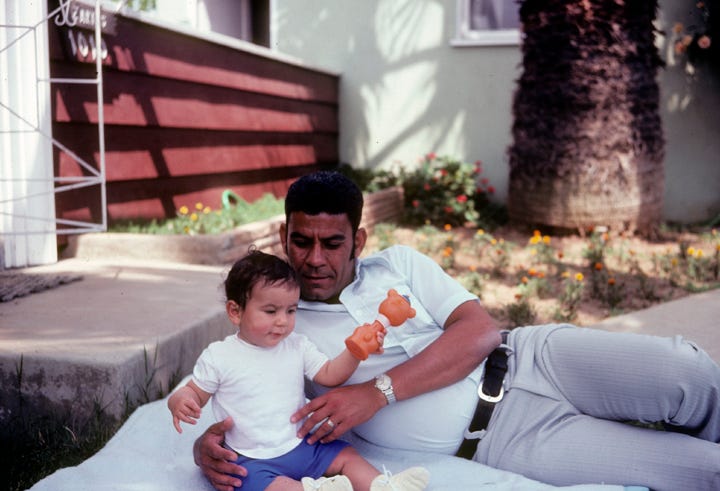

My 23andMe ancestry report indicates that I possess substantial chunks of DNA from African, European, and Asian populations. My father, who immigrated to the US, had quite dark skin, and my mother has a fair complexion.

In my childhood, I spent much of my free time outdoors playing with friends. Sunscreen was non-existent in my suburban, 1980s Southern California world, and as a consequence, I spent many summers absorbing a lot of sunlight and taking on a fairly dark hue, rarely burning. My deep black hair became very curly when I was a teenager, but not quite a proper afro. However, this didn’t stop other children from referring to my ‘fro’ on a regular basis. I have dark brown eyes, thick eyebrows, and a pronounced, medium-wide nose. In my adulthood, bald and adequately sunscreen protected, my hue and lack of hair have substantially changed the way I look, compared to my childhood.

To confound things further, I apparently present quite differently to different people and in different contexts. I am often asked, because of my name and appearance, if I am Persian, Arab, Israeli Jew, and even Japanese (with a last name like Zaki). There has never been a consensus. I traveled to Turkey and thought I looked similar to many people there. My DNA ancestry also suggests I have some Italian heritage, although no one on either side of my family knows of any Italian ancestry.

So, what’s my race? My two children, of course, inherit all of my DNA plus that of my partner, who adds South and North America to their heritage stew. They are truly “global” citizens, and they look like it, blended from ancestors who inhabited most of the world's continental land masses. So, what’s their race?

In 2023, It appears painfully evident that the concept of different and distinct races is a myth. From a biological perspective, this is nearly indisputable. Yet, legends die hard. In the United States, perhaps more pathologically than most other places on earth, people seem to hold onto this race myth as if their lives depended on it, as both oppressors and victims. The topic takes up an incredible amount of bandwidth in the media. Statistics show this trend has, ironically, been increasing despite the world's ethnic populations and cultures rapidly mixing with one another. This can be partially explained by America’s unique and tarnished past, exceptionalism, and isolation/provincialism. It can also be partially explained simply by habit. We made this bed. And we’ve been sleeping restlessly in it for centuries now.

Participation in race-based language may have some utility because it’s easy to go along with social conventions, but it is ultimately short-sighted, and I argue that we have to rip off the bandaid sooner or later, and I prefer yesterday. The reification and constant reinvention of the concept of race is deeply regressive and keeps everyone in an endless, discriminatory, divisive loop. As Carlos Hoyt, Jr. beautifully puts it, “For some of us, this false logic justifies discrimination and violence. For some of us, it leads us to try the best we can to bring about some sort of state of separate but equal state of racial equality. But we can’t. Race is predicated on separation. Separations that aren’t equal. Separate and unequal is the essential logic of race.”

The concept of separate and distinct races, as we currently understand it, is somewhere around 400 years old, which counts for roughly 0.1% of our human history on Earth. For comparison, the belief in witches lasted roughly 300 years and seems utterly absurd to almost everyone now. This is the way we evolve. Bad ideas don't last. The lesson to learn from our embarrassing history is that we must abandon erroneous ideas and move on, leaving the injustice of the past behind us and accepting the fact that there is no way to atone for it. It is the only true way to heal. This is where some fundamental Buddhist ideas can be especially useful. Realization and acceptance of the present, as it is, with all of its imperfection and suffering, is a form of liberation.

Imagine if, in order to remedy the injustices of the witch trials, we continued to speak about witches and non-witches indefinitely, blaming non-witches for discriminating against witches. That is clearly the wrong strategy. Gradually, we had to accept that witches didn’t exist and that we are all human in order to move on. The only reason race is still a powerful concept is because it serves political purposes, and it is the path of least resistance. It's a weapon used by people who have a spectrum of intentions, negative, positive, and neutral.

On one end of the spectrum, current social justice movements seem to believe that constantly acknowledging race-based systems (mainly in the form of systemic racism, an abstract force that both explains every injustice yet cannot ever be concretely located or remedied) is a way to eventually overcome racism. It’s often spoken about in terms of a seemingly endless process where folks must “do the work” for the foreseeable-to-distant future. And on the other end of the spectrum, far-right identitarians like to double down on race for obvious, old, yet sadly more rational reasons because their identity depends on racist ideas to maintain their power in a game they will, and are, losing (because melanin is a dominant phenotypic trait). Period. The human race is slowly tanning.

My view is that all parties trafficking in race are serving to maintain the status quo, which will always be inequitable, divisive, and exclusionary, especially toward those who don’t fit into any racial categories. Proof that these strategies are failing can be observed easily by looking at the toxic relationships between racialized groups as expressed by the loudest and most powerful voices on social media. We have a billion-dollar anti-racist movement with an invisible enemy. This is a recipe for an endless battle.

Given the circumstances, it is reasonable for people like me (and the millions of others who don't fit in this antiquated paradigm) to experience resentment and frustration. Every study or survey that investigates any phenomenon and uses race as a variable fundamentally ignores, within its premise, the thoughts and beliefs of anyone and everyone who cannot and will not, with a good conscience, participate and “check a box.” In a world with now 8 billion humans, many of whom can fly on airplanes across the globe in a few hours and make babies with one another, these racial categories become more absurd, literally by the minute.

Despite this reality, who is asking those of us who have parted with the delusion of race about our beliefs? Do we not have important opinions and contributions to the dialog? For example, if there were any surveys about the views that different people had about police presence, wealth inequality, immigration, taxes, political affiliations, favorite movies, or preferred ice cream flavors, the opinions of millions of people who don’t wish to self-identify in a rigged system would not be counted simply because we refuse to check a box to indicate which mythological race we belong to. The result is that we are rendered invisible and unaccounted for. Sometimes, an intellectually unsound attempt to correct this comes in the form of a “mixed race” box. I wonder, is 1/3 witch, 1/3 werewolf, and 1/3 vampire a mixed race? Mixed race is an oxymoron. There are no races to mix.

Every person who is proud of their avowed race, or denigrates others because of their perceived race, serves to maintain a delusion. Humans have a hard time letting go, especially when our egos are so embedded in a certain kind of worldview. To invoke Buddhism once again, this clinging to delusion is a major cause of suffering. Many people are searching for their original face before their parents were born, but with their eyes closed.

Now, to anticipate an obvious retort in the form of “Oh, you are one of those naive color-blind folks who pretend they don't see color,” I have a straightforward response. Color is not race. Color is color. An ethics ought not be derived from the ability to simply observe differences. When I see a person who is 5 foot 6 inches, about 150 pounds and has skin of a particular hue, I notice those superficial attributes like I notice when a tree is blossoming or which stage the moon is in. There is no causal jump from noticing color to assigning race and all the baggage that goes along with that categorical error.

Another response that I anticipate goes something like this: “That's all fine and good for you to pretend that we don't live in a racialized society, but other people will continue to discriminate against you and others, and this has consequences that lead to inequities.” To this, I say that I completely agree that I have little to no control over the way most other people think or act, even when they are wrong. This is just a fairly obvious truth that applies to many things. However, that is a weak argument for continuing to believe and perpetuate a myth. I also obviously recognize that we live in a profoundly racialized culture and that racial bigotry exists and has had awful consequences. But it's still a grave error to drink the poison simply because you are thirsty. The only thing I can do and feel obligated to do is to model the beliefs and behaviors that I know are true and to do so with the hopes that, in time, others will follow. I can, and do, treat myself and others as complex individuals with unique life stories without race, speak up when possible, and avoid treating people as part of superficial groups. I will not accept the status quo, capitulate to intellectual dishonesty, or play by the rules of a game that is fixed. I will not wait for others to stop believing in witches before I do.

My partner and I raised two children to adulthood. We intentionally did not racialize them and do not speak about anyone else in racialized terms. We did not indoctrinate them into a paradigm that doesn't stand up to intellectual or ethical scrutiny. We successfully explained the invention of the concept of race and its dire consequences without reifying it. It is surprisingly easy to do. Consequently, they have an outlook that is not racialized and do not self-identify racially. Yet, they know exactly who they are. They are honest, intelligent, compassionate, and kind humans with a rich and beautiful heritage from all over the world, like countless others. They know their original faces before their parents were born. This is how we will evolve, without race.

Amir Zaki is a Full Professor at the University of California, Riverside, in the Art Department, where he has taught photography and digital technology since 2000. His work focuses on the built and natural landscape, re-envisioning the world before him, creating a tension between the functional and dysfunctional. He is among a generation of photographers who embrace digital technology as a way to make photographs that could not have been made with traditional technologies. He has deep interests in both Eastern and Western philosophic and contemplative traditions, and he writes about popular culture with a critical approach that questions the way most people perceive identity. Check out his website. Follow him on Twitter.

I think this is the best argument for eliminativism that I have ever read. You write with clarity and the power of conviction. I share your conviction, and I thank you for sharing yours.

Amir: This was so well said. I have the pleasure of having met Carlos Hoyt (and his lovely wife) at a workshop last September and his model of revising the US census questions is brilliant and reflective of honest, fact-based data-gathering. I teach in a large private university and when I look at my students' faces I see the whole world of ethnicities, language and universal hopes and dreams. Many of them could very likely never check a box on race since they are so similar to how you describe your children. Thank you for such a clear and helpful essay.