Memoir

BILBO IS DEAD

An interracial family in contemporary Mississippi

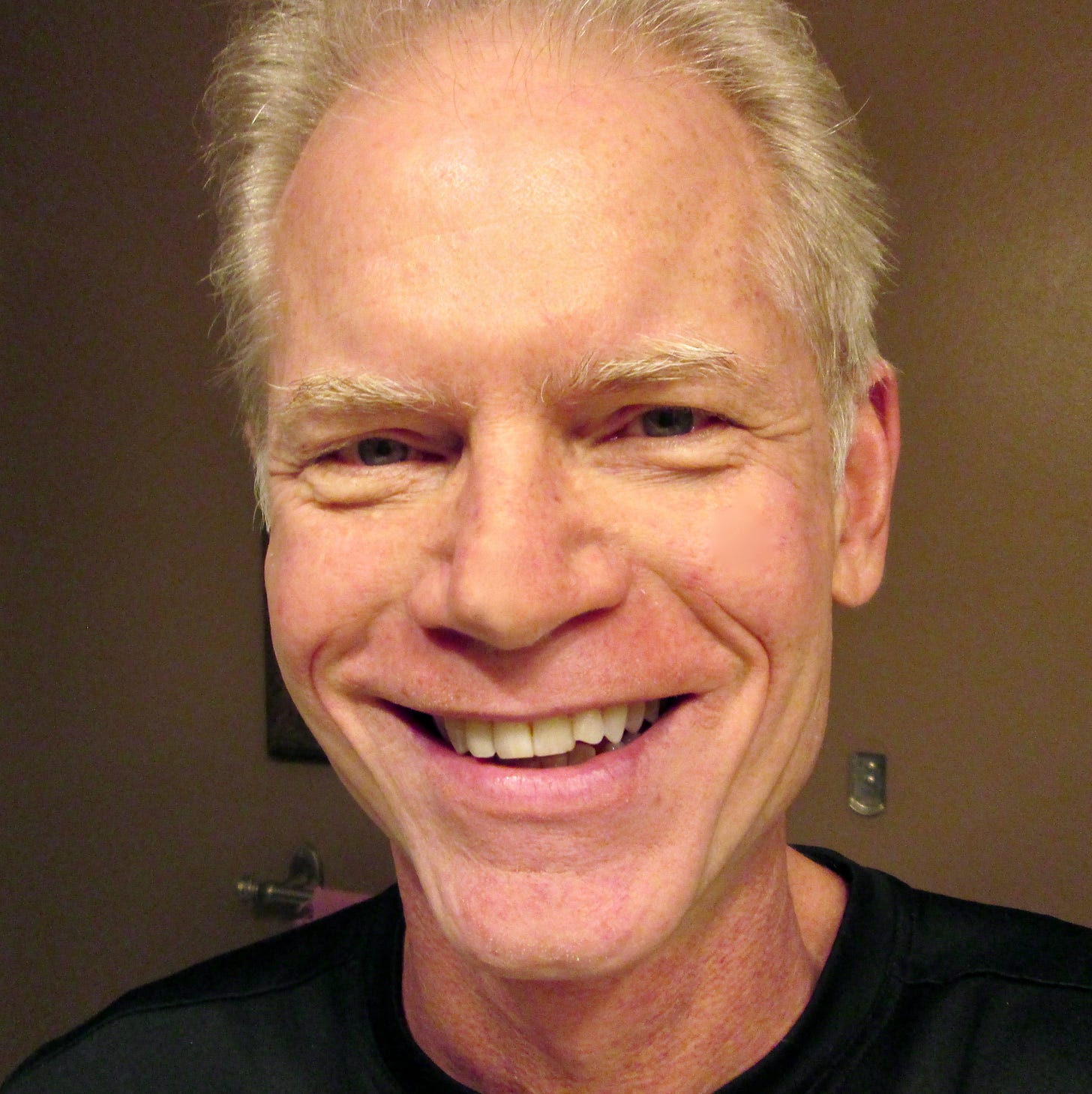

Adam Gussow

Well you’ve been livin’ in the big city, broke and had to get along

But you can hurry back to Mississippi, cause Bilbo is dead and gone

Yes he’s gone, whoa he had put it down

I feel like a lonesome stranger in my own home town—Andrew Tibbs, “Bilbo Is Dead” (1947)

2024 is a big year for my family and me. Twenty years after Sherrie and I tied the knot at Riverside Church in New York, ages 42 and 46, we’re still together—“still wailing,” as Louis Armstrong was reputed to have told the Pope of his own happy marriage to singer Lucille Wilson. Our son Shaun turned eighteen on St. Patrick’s Day, graduates high school in late May, and is off to college in the fall.

Nothing remarkable about any of this, you might say. And I’ll agree with you. We’re living the American Dream—ordinary happiness of the sort that the Declaration of Independence licenses us all to pursue. The only thing that makes us unusual, even exceptional in some people’s eyes, is that we’re an interracial family in contemporary Mississippi: the least hospitable place in America, one might have thought, for a black-and-white couple and their boisterous biracial kid. Shaun, a gifted musician with perfect pitch who can sight-read like a demon and play any instrument he picks up, is a true son of Mississippi. He’ll be matriculating at Ole Miss, where I’ve taught for more than two decades and Sherrie has worked almost as long: a music performance major specializing in trombone and euphonium. A troika of proud Rebels!

Ours is not the Mississippi story you’re familiar with. You’re familiar with the race-maddened gothic fictions crafted by William Faulkner and Richard Wright, featuring “parchmentcolored” Joe Christmas, a terrified young black man named Big Boy, and a lynching or two. We all love Jesmyn Ward down here, those of us who teach Southern Studies, but the stories she tells, haunted by loss and precarity, are not my family’s story.

You’re familiar—who isn’t?—with the riot of outraged whiteness that greeted James Meredith in 1962 when he became the first black man to register at the University of Mississippi. And you’re familiar, of course, with Faulkner’s best known saying, one trotted out every July at the Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference here in Oxford: “The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.”

But you’re not familiar with our story. And I can’t help but wonder why that is.

Is it because stories of death, trauma, and interracial violence, especially when set in Mississippi, feed a national yearning for the raw Real, for “harsh truth,” that stories of ordinary happiness do not? Or is it that the truth, our truth, would shock and offend you?

Here’s a story you haven’t heard.

It was 2022, a couple of years after the racial reckoning. My mother, who was in her early nineties at that point and who loves her only grandson, kept nudging me. Shaun was about to get his driver’s license. My mother knows, because she reads The Nation and the New York Times religiously and watches “Democracy Now,” that American roads are a killing field for young black men when they’re stopped by cops.

“You need to have the talk,” she said. “You need to warn him what’s out there.”

I’d taken the trouble to educate myself about the data with the help of Coleman Hughes, Roland Fryer, and the Washington Post’s searchable database. So I knew that things weren’t nearly as bad as she thought. But I understood why she thought what she thought: because bad news travels much further than good news, especially on social media, and because death-driven narratives and videos with a social justice valence—cops vs. blacks—had become the American national pastime, the highly monetized contemporary instantiation of racial melodrama. Still, I knew that basic due diligence was called for. Sherrie agreed.

One afternoon when Shaun was in his room playing “Black Ops III” with his gaming buddies, I asked him to take a break and join me in the living room. He came out, sat on the sofa, pushed his glasses up on his nose. He’s gotten big: six feet tall, two hundred and thirty pounds.

I wasn’t sure how to start, so I eased into the subject almost philosophically, the way a professor would.

“Are you familiar with something called ‘the talk’?”

“No.”

I was surprised. Kids these days seem to know everything, or think they do, thanks to TikTok.

“The talk is when a father—a black father—sits down with his son at some point before the son gets his driver’s license and gives him some tips about how to interact with the police if he gets stopped. Like if he’s speeding or goes through a Stop sign. Because the cop might respond differently to the kid because he’s black. So the father—”

Shaun waved his hand. “I won’t have that problem.”

“Why not?”

“Because people who don’t know me think I’m Mexican. Or Egyptian. That’s what everybody in school thought at first, until I told them about my mom and dad. So the cops won’t be a problem.”

I had rehearsed many scenarios over the years, thinking about how this moment would play out—the cloud that might pass across my son’s face as I helped him take on the full burden of his blackness, etc. But the Mexican-Egyptian angle hadn’t occurred to me.

Here’s another story you’ve never heard.

In the summer of 2021, as America limped along under the shadow of COVID lockdowns and re-openings, Shaun took his trombone up to the Square and busked. No pressure from me; he just had it in him. He set up in front of the mildewed marble statue of the Confederate soldier who keeps guard over Oxford’s big white-columned courthouse. There’d been a lot of fuss around Confederate monuments in our town over the previous two years. Back in 2019, some angry sons of the Confederacy, including a famous black reenactor named H.K. Edgerton, had marched up University Avenue into Ole Miss—an organized, pre-approved protest that sent the campus into an uproar—and rallied around the big statue at the foot of the Lyceum circle, not far from where the 1962 riot over James Meredith had taken place.

The next summer, after George Floyd was killed and statues were being toppled all over the country, the Ole Miss administration quietly relocated our monument to the Confederate graveyard, an out-of-the-way spot across campus. There’d been marches around the Square protesting the town’s own Confederate monument and its high visibility location at the top of South Lamar. But that good old boy had stayed put. And that’s where Shaun stationed himself. Because buskers want to be seen and heard.

Shaun had learned the Ole Miss fight song by that point, along with “Stars and Stripes Forever” and a handful of other marches, including “The Imperial March,” Darth Vadar’s theme from Star Wars. His curly brown hair was ramping towards a full-blown Afro. He’s fearless, our son is. I don’t know where that comes from, but I approve. He called me on my cell phone, after he’d been at it for fifteen minutes.

“Some guy literally stopped his car in front of the statue, jumped out, and threw a one-hundred dollar bill into my bucket!” he said.

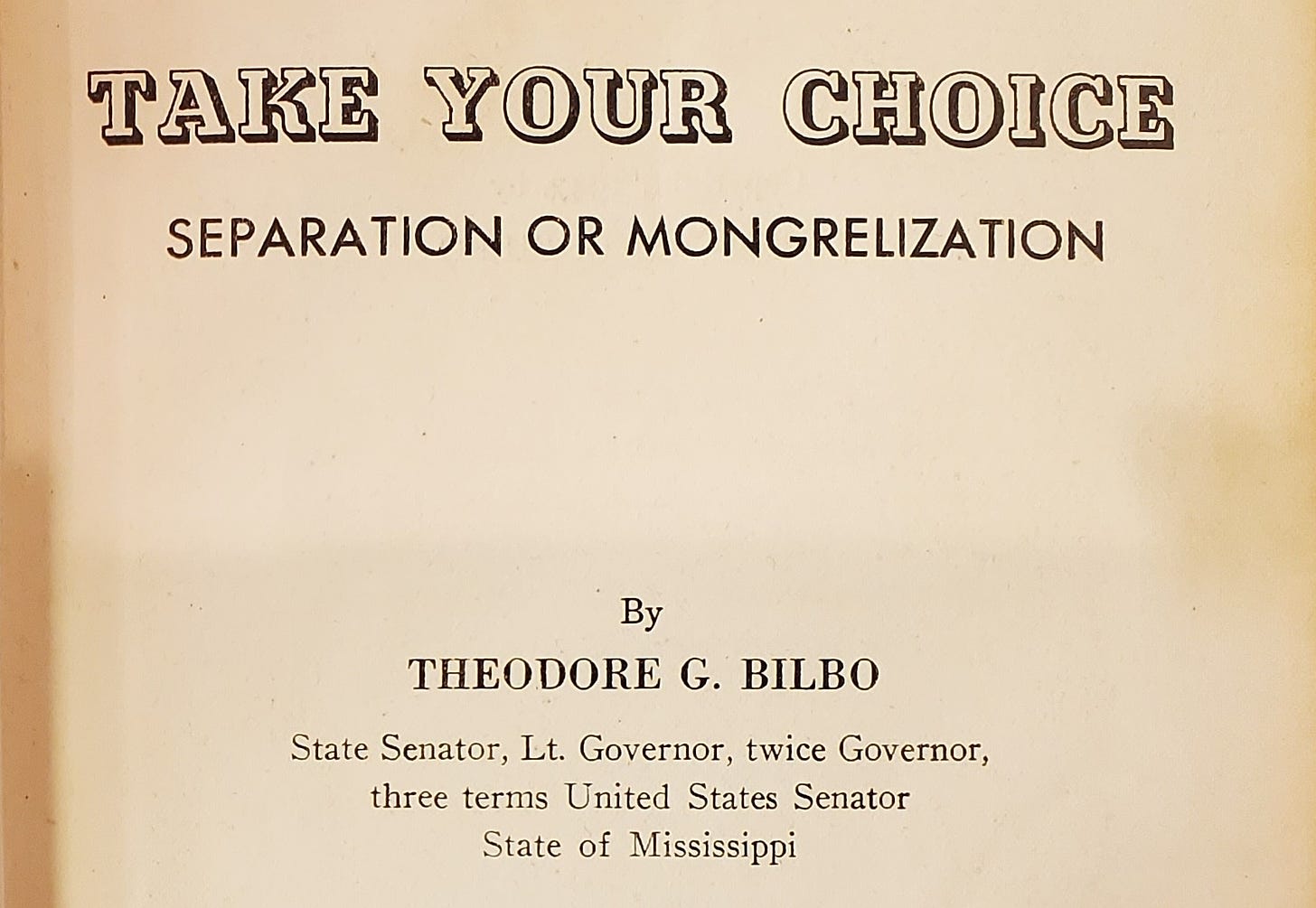

Shaun disproves every slanderous lie that white male Mississippians used to tell about people like him—how they were dangerous mongrels, the degenerate products of “race mixing,” weak-willed and conniving, etc. I used to keep a copy of Theodore Bilbo’s ethically odious screed, Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization (1947), on the desk of my campus office, hidden under some papers for easy access, just to remind myself of how bad things were in the Before Times, and how exceedingly much better they are now, especially for a family like ours.

Yet I’m also reminded almost every day that our time is troubled by its own shibboleths: ideas about race and culture and their presumptive interlinking; about the way in which the anti-blackness that Afropessimists view as foundational to America forecloses all talk of racial progress; about the ever-present threat of microaggressions and trauma requiring the creation of racially distinct “affinity spaces.”

To paraphrase James Baldwin, it seems to me that those of us, the relatively conscious race-mixers who are managing to live out the promise of America as it was envisioned by Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lewis, need to do a better job of speaking up for what we know. Bilbo is dead. He’s been dead for many decades. Beloved community remains achievable, if we but lift our heads and walk forward, fearlessly, into the light.

Thank you, James Meredith, for blazing the trail and making our Mississippi possible.

Adam Gussow is a professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi and a professional blues harmonica player. He is the author of numerous books on the blues, including Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition (2002), Beyond the Crossroads: The Devil and the Blues Tradition (2017), and Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music (2020). A longtime member of the blues duo Satan & Adam, he and guitarist Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee were the subjects of a 2018 documentary by that name that screened on Netflix for several years. His new book, Where We Are Now: Dreams of Beloved Community in a Troubled America, is slated for publication early in 2025.

So thankful for this post which mirrors my experience as a partner in a 42 year racially mixed marriage. I marvel at the acceptance of mixed-race unions in our nation and, despite the efforts of the "Afropessimists", the strides that we have made in racial/ethnic equality in general. I pray that the truth of which Mr. Gussow speaks will one day silence those who seem to long for (end presently profit from) the racial division of the past.

One more brilliant, uplifting story from a gifted writer. Thank you FBT and Adam Gussow.