Can Civic Jazz Resolve the American Dilemma?

Harmonizing individual and collective dimensions of American identity

CAN CIVIC JAZZ RESOLVE THE AMERICAN DILEMMA?

Harmonizing individual and collective dimensions of American identity

Greg Thomas

Introduction by Erec Smith, FBT President

Many musicians, theorists, and historians cite jazz as America’s distinctive musical contribution to the world. Jazz is less often acknowledged, however, as the distinctive musical representation of America itself. In “Can Civic Jazz Resolve the American Dilemma?,” Greg Thomas makes a compelling argument for the latter, and he does so by exploring Gregory Clark’s interpretation of jazz through the ideas of Kenneth Burke, arguably the most important rhetorical theorist of the 20th century, and the relevance of all three—jazz, Clark, and Burke—to democracy and civil society.

As a rhetorician, I am sympathetic to framing jazz in terms of Burke’s rhetorical theory, especially his ideas on individuality and consubstantiality, i.e., the interdependence of human beings and the way that interdependence informs our ability to communicate and work together, regardless of the diversity of our experiences and viewpoints. Thomas understands Clark’s point that both jazz and rhetoric contain “the potential to move us from one state of mind and attitude to another.” Jazz is an emergent language, one that emanates naturally from the dialectical nature of human interaction. One need not study rhetoric or jazz to know this. One need only have the experience of navigating a profoundly pluralistic society like the United States of America.

So can jazz be interpreted as, in essence, the rhetoric of the US’s diverse body of citizens? Thomas and Clark—as well as thinkers like Robert O’Meally, Susanne Langer, Ralph Ellison, John Dewey, and even Walt Whitman—help us see that jazz necessitates individuality, the rhythmic coexistence of competition and cooperation, adaptability, respect for diversity, equality, and spontaneous order, all of which reflect the classical liberalism on which America is based. Jazz, then, is the generic theme song of a robust civil society in which, by necessity, differences must be negotiated and commonalities accentuated for the benefit of each individual and of the whole.

Thomas weaves together readings of the aforementioned authors to produce a convincing argument that jazz is the “moral and artistic re-enactment of American democratic principles.” That is, believers in what Thomas calls American “civic religion” might say that a civil society made up of a pluralistic and free citizenry depends on the feeling in form that is “collective improvisation,” a term that accurately describes jazz performance. Jazz itself exhibits a transcendent spontaneous order, for a jazz ensemble, like an idealized American citizenry, emerges out of the confluence of competition and cooperation, individual self-interest, and communal consubstantiality, in a context of variety and free expression. Like jazz, America “swings.”

Thus, through his reading of Clark, Burke, and others, Thomas answers his titular question: Jazz is America. America is jazz. Acknowledging that may assuage our American dilemma.

Respectfully,

Erec Smith, Ph.D.

Can Civic Jazz Resolve the American Dilemma?

Greg Thomas

Who are we as Americans? Does an American art form such as jazz model American experience and potential? If so, how and why is this important to our understanding of American identity? In Gregory Clark’s Civic Jazz: American Music and Kenneth Burke on the Art of Getting Along, rhetoric and jazz as forms of art indeed enact the civic and civil potential of American democracy.

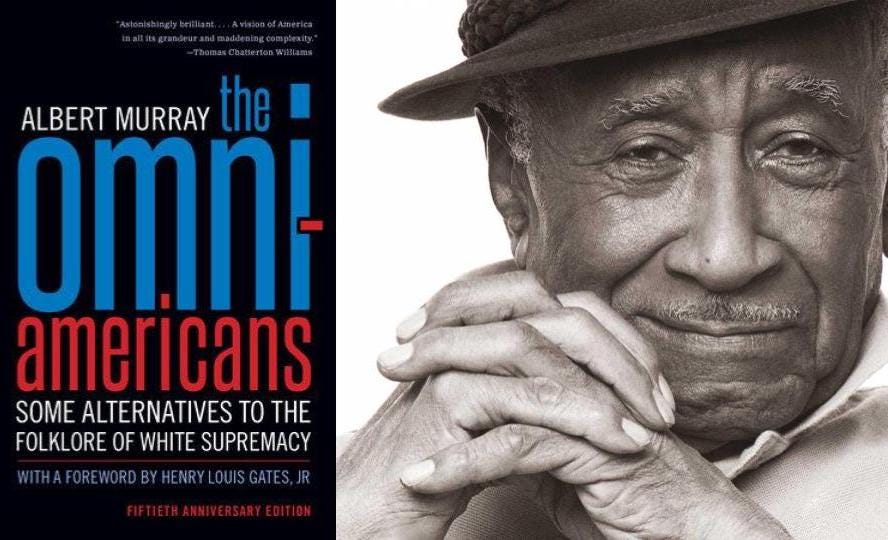

Clark, an emeritus professor of English at Brigham Young University, is a scholar of polymath Kenneth Burke, author of Permanence and Change; Attitudes Toward History; The Philosophy of Literary Form; A Grammar of Motives; A Rhetoric of Motives; Counter-Statement; The Rhetoric of Religion; and Language as Symbolic Action. Rhetoric, for Burke, extended past “persuasive propositions” into the realm of art and aesthetics. Albert Murray was fond of saying he agreed with Burke that art is “equipment for living” as well as a basis for identity. Identity, for Burke, as for thinkers influenced by the American pragmatism of Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey, wasn’t static. Rather, identity is relational, involving our internal thoughts and feelings as they interact with the social context and environment, combining subjectivity and intersubjectivity, the psychological and the cultural. In sum, for Burke, identity was a dynamic social and symbolic process and way of life.

Burke’s updated understanding of rhetoric—beyond Aristotle’s emphasis on persuasion—codified a “pattern of experience” that points to the possibility of adapting and adopting a democratic identity:

In Kenneth Burke’s concept, the rhetorical and the aesthetic—argument and art—necessarily combine, and in America they combine in the project of shaping individuals in the image of interdependent independence that follows from the civic ideal of e pluribus unum. That so many Americans seem unwilling to claim that interdependence along with their independence, even to admit to it, has always been this nation’s basic civic problem.

—Gregory Clark, Civic Jazz, p. 26

According to Clark, jazz is the quintessential democratic art, which creates human experiences of civic and civil democratic form in action, which Burke called “symbolic action.” Form, in Burke’s theory, does not denote solely the shape and structural components of an artifact. An individual or audience of readers, listeners, and viewers co-create the form of an artifact in their experience of it. That’s why the experience of art is not purely individual but cultural and intersubjective. Art contains the potential to move us from one state of mind and attitude to another as we engage in and with it. This is akin to the way we are carried along by the experience of a plot in a story or by the syncopated rhythms of jazz.

Clark relates his own experience of witnessing live jazz and listening deeply to recordings. He incorporates ideas from Duke Ellington, Marcus Roberts, Vijay Iyer, Wynton Marsalis, and others to drive home his points. For instance, his quotation of Prof. Robert O’Meally, founder and director of Columbia University’s Center for Jazz Studies, from his edited collection of Ralph Ellison’s writings on jazz, Living with Music, is exemplary:

“With its insistence on individuality of sound…and on the capacity to swing with and against one’s fellow players; its accents on improvisation and readiness for changes; and its connections with the comedy laced by tragedy that defines the blues, jazz is a musical language that reminds us what and where we are as US citizens.”

In what Clark describes as Burke’s “profoundly rhetorical theory of aesthetic form that treats art as an assertion of influence,” an idiom such as jazz “is immersive, emotional as much as intellectual, even spiritual when it lets two or more people feel themselves transcending the differences that divide them for a moment or two” (p. 10). This “feeling in form,” as American philosopher Susanne Langer would have put it, is key for Burke’s style and strategy of rhetoric.

Feeling follows from experience and experiences are made aesthetically, with “aesthetic” understood as a design to bring a feeling into being through a sequence of encounters with perspective and attitude that culminates in a sense of oneself that is more or less different from before. That’s how Burke’s redefined rhetoric shifts the aim of influence from opinion to identity, and how his redefined aesthetic relocates art from the artifact to the experience of identity that an artifact provides.

—Gregory Clark, Civic Jazz, p. 38

Democratic Vistas Through Art

Understandably, after the Civil War ended in 1865, Walt Whitman’s faith in the process of democracy through politics was shaken. In his 1871 book Democratic Vistas, he looked beyond political democracy to a “social, or esthetic democracy” for a “moral and artistic” identity. Whitman’s own poetry invited audiences into an experience of shared identity as Americans, but, arguably, it is only with the creation of jazz that one finds the moral and aesthetic re-enactment of American democratic principles via collective improvisation, where the individual is respected and acknowledged in a group striving for that ensemble mindset flow called “swing.”

Clark agrees and extends the point even further:

Perhaps jazz is the music of democracy not so much because it so well melds individual and group, freedom and order, though that is crucial, but because it does so through joint acts of faith. Jazz musicians play the music upon the belief that something beyond themselves will be manifest there—something that expresses, in William James’s phrase, ‘immense elation and surrender, as the outlines of the confining self-hood melt down.’

—Gregory Clark, Civic Jazz, p. 76

An American Civic Religion?

If the call for “joint acts of faith” has a religious ring, that’s fine. As Beth Eddy demonstrates in The Rites of Identity: The Religious Naturalism and Cultural Criticism of Kenneth Burke and Ralph Ellison, both Burke and one of his most perceptive interpreters, Ralph Ellison, were concerned with “religious traditions and experiences as naturally available to human beings without the attribution of any special supernatural powers to any human ideals.” As men of letters, Burke and Ellison were like anthropologists of language, highlighting how humans—“symbol-using animals,” in Burke’s words—employ language to determine sacred and sacrificial meaning.

John Dewey, whose meditations on form in Art and Experience influenced Burke, once wrote that the primary tenet of an authentic American civic religion was “the continual disclosing of truth through directed cooperative endeavor.” Riffing on Dewey, Clark writes:

Religion is about transcendence, and e pluribis unum is an aspiration as transcendent as any. […] Religion is also about sacrifice, and jazz music can show us a kind of cooperation that demands a profound sacrifice of self, the kind in which a better self can sometimes be discovered. This is how jazz is intensely rhetorical in the very way religion is: its project is to prompt others to progress beyond selfishness by enabling then to comprehend in themselves a person whom joining with others might let them become. And like religion, jazz draws upon the resources of rhetoric and aesthetics to let those who experience it experience that self rationally and emotionally, systematically and intuitively, all at once.

—Gregory Clark, Civic Jazz, p. 32

Of course, the democratic pattern of experience and way of life as demonstrated in the art of jazz is far from easy. To play jazz well, one has to go deep in the shed of practice and performance with others; to be an American citizen living and embodying the constitutional principles laid out in our founding documents, we have to allow for the shedding of limiting identities such as racial essentialism and an embrace of a rooted cosmopolitanism. The pluralistic tensions of democratic life in a multi-ethnic open society, where one has to be willing to risk changes in identity as we engage with each other in linguistic, artistic, and political communication, is an obvious source of division in the United States.

Clark argues that we can learn from Burke and from jazz that the tension between the individual and the community can be constructive and generative. One answer to the inquiry in the title of this post is to say that resolving conflict is not the goal; rather, the “goal is to learn that sometimes we can understand opposition as interdependence” (Gregory Clark, Civic Jazz, p. 21).

That’s what Ellison and Murray called “antagonistic cooperation,” and what Burke described as the “competitive use of the cooperative.” For the jazz musician, this typifies what Ellison called the “true jazz moment.”

Each true jazz moment springs from a contest in which each artist challenges all the rest; each solo flight, or improvisation, represents (like the successive canvases of a painter) a definition of his identity: As individual, as member of the collectivity and as a link in the chain of tradition. Thus, because jazz finds its very life in an endless improvisation upon traditional materials, the jazzman must lose his identity even as he finds it . . .

—Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act, p. 234

The Mystery and Frustration of American Democracy

Modernity and its classically liberal emphasis on the dignity of individual persons often rubs up uncomfortably against group allegiances such as our families, our ethno-cultural origins, and even a national identity. Above, we’ve alluded to rooted cosmopolitanism as one hopeful way to confront such a dilemma, whereby one can be local and rooted as well as global and cosmopolitan simultaneously.

But such a philosophical orientation still doesn’t completely resolve the tensions apparent in the world’s first multi-ethnic democracy. Another courageous attempt is Albert Murray’s “Omni-American” concept, a dynamic equilibrium between the “many” distinct individual and group identities and an emergent American whole—the “one”—grounded in our founding principles in action.

Ellison, whom Harvard philosopher Danielle Allen deemed “one of the greatest democratic theorists of the twentieth century,” published a classic essay in 1978 deeply informed by Burke’s thought, titled “The Little Man at Chehaw Station.” In it, Ellison discusses the role of art, artistry, and individual agency in a democratic context, and the challenges of communicating across difference within American culture and society. The tensions he outlined then are still painfully apparent today:

[I]t would seem that for many our cultural diversity is as indigestible as the concept of democracy in which it is grounded. For one thing, principles in action are enactments of ideals grounded in a vision of perfection that transcends the limitations of death and dying. By arousing in the believer a sense of the disrelation between the ideal and the actual, between the perfect word and the errant flesh, they partake of mystery. Here the most agonizing mystery sponsored by the democratic ideal is that of our unity-in-diversity, our oneness in manyness.

Pragmatically we cooperate and communicate across this mystery, but the problem of identity that it poses often goads us to symbolic acts of disaffiliation. So we seek psychic security from within our own inherited divisions of the corporate American culture while gazing out upon our fellows with a mixed attitude of fear, suspicion and yearning.

We repress an underlying anxiety aroused by the awareness that we are representative not only of one but of several overlapping and constantly shifting social categories, and we stress our affiliation with that segment of the corporate culture which has emerged out of our parents’ past—racial, cultural, religious—and which we assume, on the basis of such magical talismen as our mother’s milk or father’s beard, that ‘we know.’ Grounding our sense of identity in such primary and affect-charged symbols, we seek to avoid the mysteries and pathologies of the democratic process.”

—Ralph Ellison, “The Little Man at Chehaw Station” (1978)

This is the mystery and frustration of the democratic process in the United States: striving to make e pluribis unum, “out of many, one,” a lived, egalitarian reality in which our differences don’t erase what we hold in common nor what Lincoln in his first inaugural address called “the greater angels of our nature.” I wonder: What aspects of our current identities (e.g., racial) are we willing to let go of in order to find a higher octave of shared identification? What parts are we willing to let die or to be transformed into something different and better, so we co-create a shared American identity?

That, indeed, is the question.

Free Black Thought is a proud sponsor of the “Resolving the Race(ism) Dilemma” conference featuring Greg Thomas, Carlos Hoyt, and Sheena Mason, to be held in Lexington, MA, on Sept. 24, 2022. It’s not too late to register!

Greg Thomas is CEO of the Jazz Leadership Project, a firm that uses the principles and practices of jazz music to enhance leadership success and team excellence in organizations such as JPMorgan Chase, Verizon, Center for Policing Equity, TD Bank, and Google. Greg is a professional writer and a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Cultural Evolution. In October 2021, he co-produced the two-day broadcast, "Combating Racism and Antisemitism Together: Shaping an Omni-American Future," which may be viewed here and here. He blogs at Tune In To Leadership, where an earlier version of this essay first appeared. He co-authored Reimaging American Identity with his partner, Jewel Kinch-Thomas, and Amiel Handelsman. He has published previously in the Journal of Free Black Thought here and here.

Beautiful piece, much to taste and digest

Terrific piece, beautiful thoughts beautifully stated. Thank you.