Poetry

COUNTEE CULLEN’S LYRIC GHOSTS

The apostrophe to Keats in “To John Keats, Poet. At Springtime”

Maximilian Werner

Editors’ note: This is the first of two essays on African-American literature by Maximilian Werner that we will publish in JFBT. The second essay, on Richard Wright’s 1940 novel Native Son, will appear in a few days.

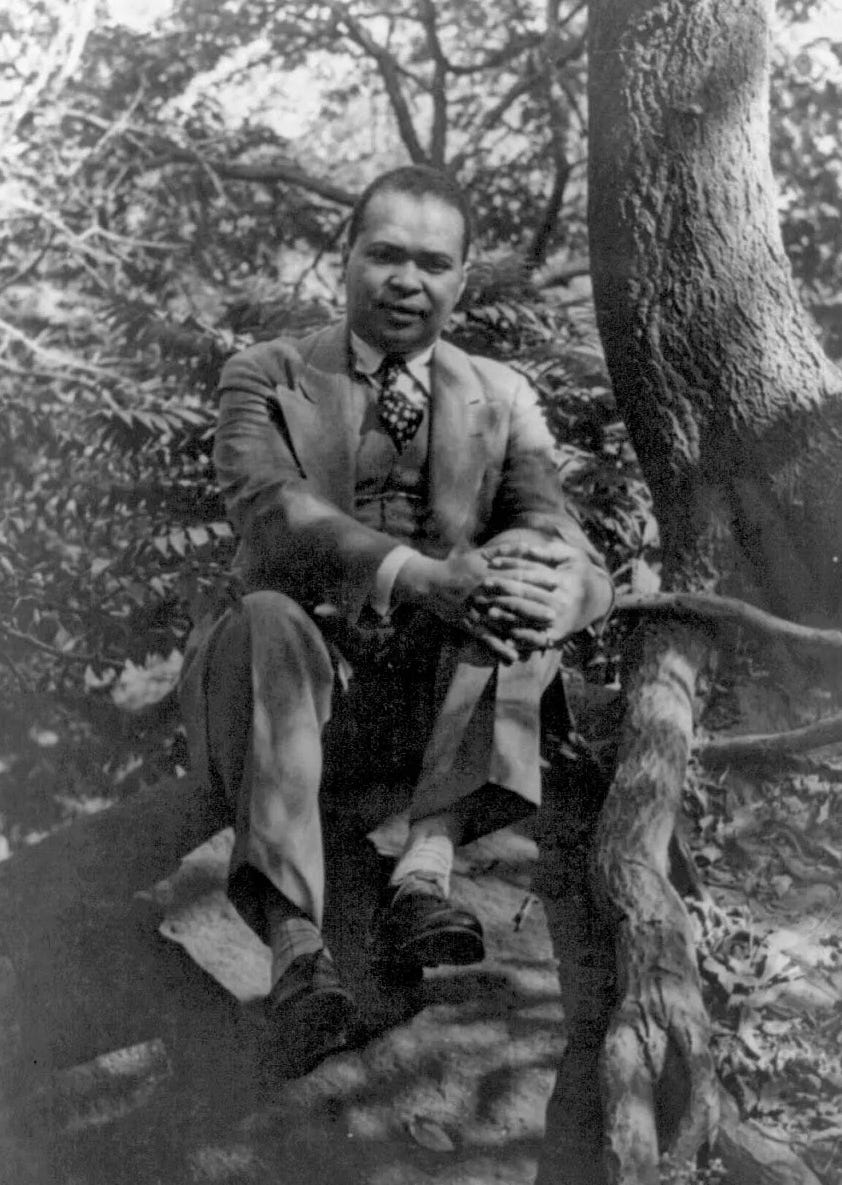

“I cannot hold my peace, John Keats.” So the Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen (1903 – 1946) opens his poem “To John Keats, Poet. At Springtime,” in his 1925 collection of poems, Color. He continues: “There never was a spring like this; / It is an echo, that repeats / My last year’s song and next year’s bliss” (stanza 1, lines 1-4). To be sure, the unrest of these lines parallels the fitful changes of spring, and thus becomes the “tocsin call” (stanza 2, line 6) which signals the transformation about to take place. It is not, however, “merely spring” (stanza 4, line 8) which undergoes change, for the speaker of Cullen’s poem, or rather the singer of his song, via his apostrophe to Keats, ushers in his own “Vision Splendid to a birth” (stanza 3, line 10). It is a vision of which we, as readers, are also witnesses. This essay traces the lyric ghosts of John Keats’s 1819 poem “Ode to a Nightingale” in Cullen’s “To John Keats.”

Late in “Heritage,” in the same collection, Cullen writes, “Lest the grave restore her dead.” What is spring if not a restoration of the dead? The speaker of “To John Keats” is not an exception, for he already seems to speak from the grave when he says of spring, “It is an echo, that repeats / My last year’s song and next year’s bliss.” Although it is possible to read “last year’s” as the preceding year, given the subject and tenor of the poem, a more plausible reading would be final year. For unless the speaker were in fact speaking from beyond the grave, how could spring be an echo which repeats next year’s bliss when next year has not yet arrived? Consequently, taken together these lines suggest the collapse of time as well as the boundaries between life and death.

An apostrophe normally involves “addressing a dead or absent person as if it were alive, present, and capable of understanding” (Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics). The strange familiarity with which the speaker addresses Keats in the first line of “To John Keats” would seem consistent with the above definition. We get the sense, however, that the relationship between the speaker and Keats transcends understanding in any ordinary sense. “I know,” says the speaker, “in spite of all men say / Of beauty, you have felt her most” (Stanza 1, lines 5-6). The speaker’s apostrophe here is not simply a matter of speaking to and being understood by Keats. It is, rather, a matter of “knowing” what Keats has felt and is feeling as his fingers “push / The Vision Splendid to a birth” and thus “work as grass in the hush / Of the night on the broad sweet page of the earth” (stanza 3, lines 11-12). Consequently, the limitations of our conception of the apostrophe are revealed. For although the speaker’s apostrophe would imply that he speaks with the tongue of the living, he knows what Keats, “Though dust” (stanza 3, line 9), feels and thus seems to be dead himself or, like Keats in “Ode to a Nightingale,” “half in love with easeful Death” (stanza 6, line 2).

In his Ode, Keats “Call’d [death] soft names in many a mused rhyme, / To take into the air [Keat’s] quiet breath” (stanza 6, lines 3-4). For Keats, death was the medium which, once embraced, would allow him to “[Sing] of summer in full-throated ease” (stanza 1, line 10), that is, eternally. Springtime has a similar function for the speaker of Cullen’s poem who, although he too has encountered “death’s dark door,” (stanza 3, line 8), cannot resist spring’s “tocsin call to those who love her” (stanza 2, line 6). It is almost as if the speaker of Cullen’s poem is saying to Keats, “Now more than ever seems it rich,” not “to die,” as in the Ode (stanza 6, line 5), but rather to be reborn. This spiritual and artistic camaraderie becomes evident when Cullen’s speaker asks, “And you and I, shall we lie still, / John Keats, while Beauty summons us?” (stanza 3, lines 1-2).

Readers would be mistaken, however, were they to conclude that the affinity—the “Vision Splendid”—shared between the two poets was exclusive. For we readers are implicitly invited in to “Keep revel with [Keats and Cullen], too” (stanza 4, line 10). When Cullen writes, “while my head is earthward bowed / To read new life sprung from your shroud” (stanza 4, lines 5-6), does he not invite us to bow our own heads earthward as we read new life springing from Cullen’s own shroud, that is, from his poem? And as a result, do we not also hear the “full insistent cry” (stanza 4, line 2) of Keats’s “Wild voice” (stanza 3, line 7) via Cullen’s own? We are likened to the speaker of Cullen’s poem and our relation to him parallels his relation to Keats. Consequently, we become self-aware because our identity seems to merge into the speaker’s own, and we wonder if he addresses us and not merely Keats when asks, “And you and I, shall we lie still?” (stanza 3, line 1).

The distinctions among ourselves, Keats, Cullen, life, death, last year, and next year disappear in springtime, which contains all of these things at once. Thus it may seem odd to many readers that, “While white and purple lilacs muster / A strength that bears them to a cluster” (stanza 2, lines 11-12)—that is, while spring has the strength of joining together what appears or is thought to be different—Cullen seems to minimize the importance of spring when he writes: “Folks seeing me must think it strange / That merely spring should so derange / My mind” (stanza 4, lines 7-9). But just as Cullen’s use of apostrophe was found to diverge from its conventional definition and application, so too do his words “merely” and “derange.” Merely at first seems to denote “only as specified, and nothing more; simply.” Etymologically, however, merely comes from the Latin merus, which means “not mixed” or “pure,” a meaning that underscores spring’s ability to “mix” and thereby undermine the distinction between seemingly disparate ideas.

While the word “derange” usually has a negative denotation, when we look at the etymological meaning of the word’s prefix we see that the word is also compatible with the merging described thus far. For the Latinate prefix de can possess the sense of “undoing” or “reversing,” while the word “range” means “to divide into classes or classify.” When combined, the etymological sense of “derange” is “undoing or reversing classification,” which is precisely what Cullen has done by presenting us with the extraordinary affinity between the speaker and Keats, not to mention ourselves.

As readers we are merely (purely) joined to the speaker and to Keats by way of Cullen’s song, which itself is an echo that transcends both time and space. It is possible now to see just how inclusive Cullen’s vision is when he writes, “All things that slept are now awake” (stanza 2, line 14). Cullen’s splendid vision occurs, then, in the way that his use of apostrophe creates parallels which collapse the differences between life and death, white and purple, song and singer.

Maximilian Werner is an accomplished author and Professor in the Department of Writing and Rhetoric Studies at the University of Utah. With over two decades of teaching experience, he specializes in courses such as Intermediate Writing, Environmental Writing, and Writing about War.

Werner holds an MFA from Arizona State University and has published seven books. His works include the novel Crooked Creek, the memoir Gravity Hill, and the essay collections Black River Dreams and The Bone Pile: Essays on Nature and Culture. His poetry collection, Cold Blessings, and his nonfiction work, Wolves, Grizzlies, and Greenhorns: Death and Coexistence in the American West, further showcase his diverse literary talent.

His writing often explores themes of nature, culture, and the human experience, particularly in the context of the American West. Werner’s creative and scholarly work has been featured in numerous journals and magazines, including The Robert Frost Review, The Ecological Citizen, Times Higher Education, The Emerson Society Papers, Inside Higher Education, Counterpunch, and The North American Review.

In addition to his literary achievements, Werner is recognized for his contributions to environmental and cultural discourse, making him a respected voice in both academic and literary communities.

Love this. We don’t talk enough about the Harlem Renaissance, Negritude & its vibrant debates, discovery & celebration that reverberate today.

This inspired a post of mine. This is a backlink.

https://whyweshould.substack.com/p/werners-cullens-keats