From Hungary to Haiti: Unique Histories, Universal Stories

Personal reflections on our shared human condition

Memoir

FROM HUNGARY TO HAITI: UNIQUE HISTORIES, UNIVERSAL STORIES

Personal reflections on our shared human condition

Ildi Tillmann

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

—Rumi

Introduction

I’m an author and photographer working at the crossroads of art and documentary. I was born and raised in Hungary, have lived in Israel, and currently reside in New York. I have a law degree from Hungary and an MA in Africana Studies from SUNY, Stony Brook. Through my written and visual work, I explore themes that connect cultures, regions, and individuals. Addressing the complex and the contradictory, I focus on stories that have relevance across ethnic, religious, and racial boundaries, and that mirror those aspects of the human condition that burden and grace us all. From Eastern Europe to Haiti, here are some of my recent reflections.

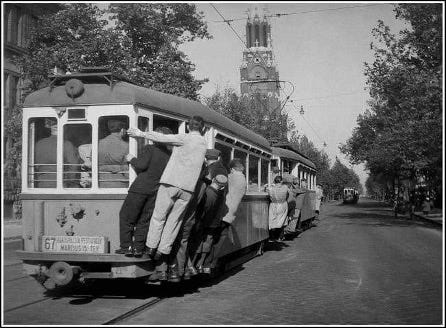

1. Eastern Europe, 1940-1960s: images from recorded history

In her Introduction to Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1945-1956, Anne Applebaum paints a vivid picture of both the broader historical and the lived, individual realities of post-war conditions in Eastern Europe. She writes (p. xxv):

[T]he year 1945 marked one of the most extraordinary population movements in European history. All across the continent, hundreds of thousands of people were returning from Soviet exile, from forced labour in Germany, from concentration camps and prisoner of war camps, from hiding places and refuges of all kinds. The roads, the footpaths, tracks and trains were crammed full of ragged, hungry, dirty people.

The scenes in railway stations were particularly horrific to behold. Starving mothers, sick children, and sometimes entire families camped on filthy cement floors for days on end, waiting for the next available train. Epidemics and starvation threatened to engulf them. […]

By 1945 […] the lethal armies and vicious secret policemen of not one but two totalitarian states had marched back and forth across the region, each time bringing about profound ethnic and political changes. […] The Germans considered the Slavs to be subhuman, ranked not much higher than the Jews, and they thought nothing of ordering arbitrary street killings, mass public executions, or the burning of whole villages in revenge for one dead Nazi.

The Soviet Union, for its part, “considered its Western neighbours to be capitalist and anti-Soviet strongholds” and treated the civil populations of the region accordingly. The immediate post-war years witnessed mass deportations, politely called, in the official jargon, “population exchange agreements,” which meant that individuals belonging to ethnic groups deemed guilty of starting the war were relocated to countries where they were not born, typically had never lived, but were declared now to belong.

However, in the post-war peace, life resumes. Applebaum quotes a Polish observer (p. 6):

In the ruins of the streets, there is commotion like never before. Trade – buzzing. Work – booming. Humour – everywhere. The mob, teeming life, flows through the streets, nobody would think that these are all victims of a massive disaster.

And a Hungarian:

People were quibbling over prices for warm British clothes, French perfumes, Dutch brandy and Swiss watches among the rubble.

Poles and Hungarians alike “speak of how desperately they sought education, ordinary work, and a life without constant violence and disruption.”

In spite of such hopes—and during the same time that Western Europe received aid through the Marshall Plan to rebuild after the war—the East lingered under the weight of yet another totalitarian regime, literally separated from freedom and opportunity by walls, fences, barbed wire, and armed border guards with strict orders to shoot.

2. Eastern Europe, early 20th century: my family

The twentieth-century history of my family, as that of most in the region, was heavily influenced by the era’s preoccupation with social groups and social identity. My paternal great-grandmother came from an orthodox Jewish family from a small village located in current-day Slovakia. When she was 17 years old, she met a Hungarian Protestant man, they fell in love, and, after she converted to Protestant Christianity, they got married. Her family, in agreement with and strengthened by the support of members of the only community she’d ever known, disowned her for her choice, which amounted to disrespect of God. My great-grandmother moved to Hungary with her husband and was never contacted by her family again. She was a dissenter from community norms, a woman of her own will, and thus apparently undeserving of acceptance. She and her husband had five children. She died of tuberculosis when my grandfather, her youngest, was two years old.

My grandfather was thus raised as a Protestant, with no knowledge of his Jewish heritage. Given the context of early twentieth-century Eastern Europe, such ancestry was frequently hushed up. When he turned 26, my grandfather married a Transylvanian Protestant woman and, in 1937, they had a son, my father, whose childhood unfolded against the backdrop of the Second World War. When my father was two years old, his parents divorced and, in order not to inconvenience his mother, he was sent to live with her parents (my great-grandparents) in Transylvania—a part of Romania since the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 and, at the time, home to over a million ethnic Hungarians.

In 1944, when the Soviet army was pressing ahead against the Nazis on the eastern front, and the fighting approached the town where my father and his grandparents lived, he was sent to the Hungarian capital, Budapest, to be with his mother. He traveled alone, by train, during intermittent air raids, with a note in his pocket containing the name and address of his mother. My grandmother’s new husband refused to allow my then seven-year-old father to live with them, so he was left in the care of his father, who, despite his Protestant upbringing, was considered Jewish under the law. His father—my grandfather—was more fortunate than many. He was not transported to a concentration camp by the Germans but assigned to a Soviet forced-labor unit during the siege of Budapest, tasked with transporting explosives from one part of town to another for the Soviet army in the middle of shelling and bombing raids. Thus, my father ended up alone in a city under siege. He was taken in by a woman from the countryside, someone who saw him neither as ‘another’s son’, nor as the ‘half-Jew’, but as a little boy alone. She is the reason he survived the war.

Early in the Soviet era, some in my father’s family were deported to a small village in Hungary, as part of an internal displacement scheme for members of the former aristocracy, the middle-class, and the intellectual élite, this last category being the one to which the family belonged. These classes were, that is, the ‘oppressors’, ‘the suspicious’, and the ‘enemies of the people’.

On my mother’s side, life was no less eventful. My maternal grandmother’s first husband, a career officer in the Hungarian army that had supported the German side in the war, was executed by the new Soviet regime. When the Soviet troops liberated our country from German occupation and ended the rule of Hungarian collaborators, they simultaneously stationed their own soldiers in the region, to ensure that our liberation would never end.

In 1968, my uncle, my grandmother’s son from a second marriage, liberated himself and left Hungary for the West, swimming across the sea from a small village in the former Yugoslavia to Italy in the middle of the night. He left with two other young men, one of whom, his best friend, drowned on the way. My uncle and his surviving friend were taken to an Italian refugee camp from which they later escaped and walked to Switzerland, because the Italian authorities planned to send them to Australia. White faces against the backdrop of the blue Mediterranean Sea and the rolling hills of the Alps. Neither ‘victims’, nor ‘survivors’. They are real human beings.

Before the Hungarian revolution against the Soviet regime of 1956, travel outside the borders of the Soviet Bloc was almost impossible, and even during the decades of gradually softening political oppression, it continued to be difficult. We had two different passports: a red one to travel to Socialist countries, and a blue one to travel to countries outside of the Bloc. Blue passports were not automatically granted, and they were routinely denied on political grounds: the opportunity to travel to the West, which, for us, represented opportunity and freedom, was used as leverage, as a tool of control to ensure that people stayed in line, at least openly. Even in the 1970s, blue passports could be requested only once every three years, then in the 1980s, once a year, for one single, specific trip, and they were only valid for that occasion. Like everybody else from Eastern Europe, Hungarians also needed visas to enter countries outside the Soviet Bloc. The lines for visa applications in front of embassies of desirable destination countries, such as Germany or the United States, were routinely many hours long. Visas could be and were granted or denied arbitrarily.

The stories could go on. Stories from my history, a ‘white’ history, human history, our history.

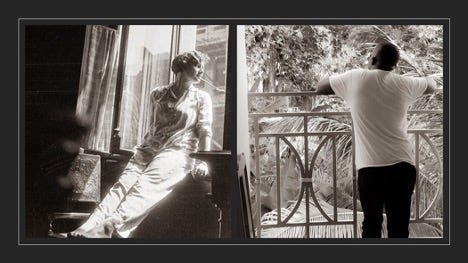

3. From Hungary to Haiti: the notion of home

In the year 2000 I moved to the United States. I was not fleeing oppression or poverty; I was married to a man who was offered a job in Colorado. In 2015, I applied to graduate school in Africana Studies and my research topic led me to Haiti.

Before my first trip to Haiti, I had been warned many times that I was going to a place not much short of the belly of the beast and that, particularly insofar as I was a ‘white woman’, I would likely be shocked to see the realities on the ground. I heard the warnings, but the main effect they had on me was to make me wonder how little people seem to know about global history. It caused me to reflect on the slanted perspectives from which we construct and tell human stories, no matter which country we come from. Most of all, it led me to reflect on the notion of home.

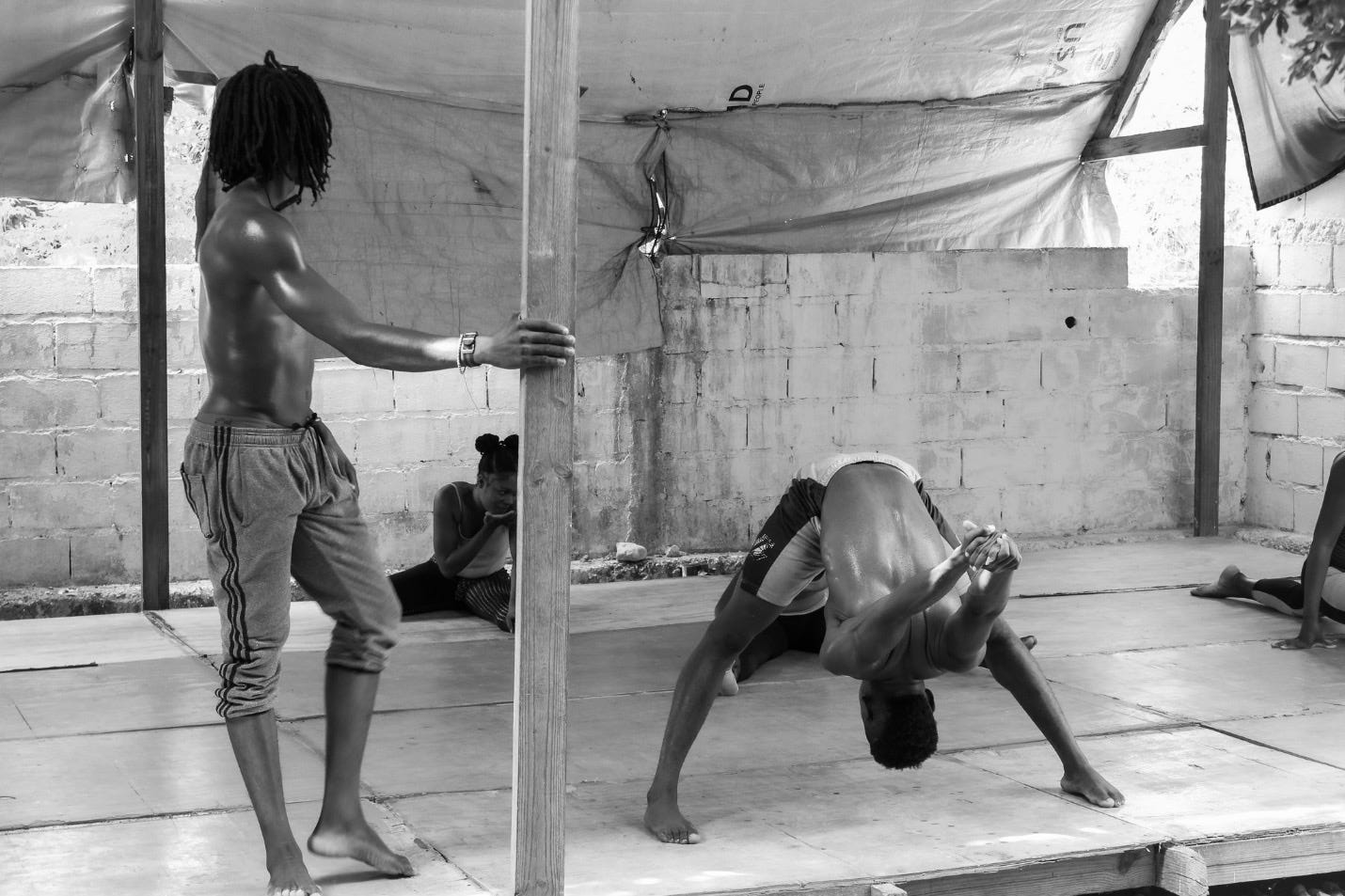

While it was immediately clear to me that daily life in Haiti was physically and emotionally demanding for a great many of the people living there, my reaction to what I saw was not bewilderment or the activation of the ‘savior instinct’ expected of me. Rather, it was a vague feeling that, after almost two decades of living abroad, I was finally at home. Not in the geographical sense, clearly, but in the sense that I recognized the way individual people reacted to daily conditions in which they could only rely on their own strength and ingenuity. I saw a national community whose individual members had routinely to overcome challenges posed by their daily conditions and not despair. I saw people determined to change a chaotic economic and political system that held them captive, while also having to operate within the rules and the opportunities shaped by that very same system. For me, that was home.

Take the story of a journalist I met. This individual (who must remain nameless) is college-educated and, in addition to his native Creole, speaks fluent French. He periodically works for local news stations and, occasionally, for the French media when their programming menu needs a bit of Caribbean flavoring. Mostly, for many years, this journalist has been in and out of jobs. About three months ago, he had to flee the place where he lived and has been alone in hiding, unable to work or see his loved ones. For a while he was hiding in an empty school building, with hardly any food or drinking water. The reason? He contributed, as an independent analyst, to a local radio program reporting stories about the worsening gang violence. As a rule, major gang leaders in Haiti have their own paid journalists, who report supervised content about the details of the violence, or the messages of the gangs. A gang leader from the area where this journalist lived decided that his independent reporting was not what he wanted to hear on the radio, so he sent people to kill him. He barely escaped with his life. A few days ago, I saw an update on his WhatsApp account, which reflected fear and despair, and, above all, a desire to return home and to see his family. A desire for peace and normalcy.

Or take the story of a little girl who was born in October 2019, in the middle of rising political violence, accompanied by the light and smoke of burning barricades and a resulting national lockdown that lasted for months. When, during the night of her birth, I was on the phone with her father—a man who must stay anonymous, but who is fluent in French and holds a degree in psychology, but can get no reliable work—we were not sure whether they could make it to a clinic for medical help. They did make it, and the girl was born healthy, but her birth was not the happy ending of a ‘story of hardship and challenge’, as it might at first appear, or as it might be advertised on a site run by a nonprofit for a US audience. This wartime birth was the anguished beginning of the little girl’s life, a human life that has been unfolding against a backdrop of destruction, insecurity, resilience, and hope but also, at times, desperation.

Each time I went to Haiti and talked to people there, I understood that this was a community whose individual members have been through authoritarian regimes, political violence, and economic insecurity – just as my own family had. I recognized the stories of fear and violence from the time of the Duvalier dictatorship, and those of the collective punishment of the dechoukaj afterwards, once the regime gave in. (Note: “dechoukaj” is a Creole term which means “uprooting”. In Haiti, it is used to refer to larger-scale political upheavals which include violence and looting, typically with the goal to eradicate a political regime. In the US, it is mainly used by historians when describing the outbreak of violence that followed the overthrow of the Duvalier regime in 1986. It was characterized by mass violence against people who supported the regime, or who were presumed to be supporters.)

I understood that beyond the foundational story of colonial slavery and racial discrimination, Haitians have had to live with the reality of home-grown violence, corruption and class-based prejudice, recorded and analyzed in detail by historians and sociologists, such as Alex Dupuy, Michelle Trouillot, Laennec Hurbon, or Robert Fatton Jr, among others, and that, just like the Hungarians and the Poles described in Applebaum’s book, what they desperately have sought was education, ordinary work, and a life without constant violence and disruption. Again, I was at home.

At home in the car repair shop located in the neighbor’s dusty yard, and at home in situations where things routinely simply did not work. Where service, as such, was not something people are entitled to, but was something one received if someone in a position to give it was in a generous mood and gave. I felt at home in the small stores where the shelves were either empty or stocked with prepackaged and wilting products that had clearly seen better days. Despite all the apparent, but in the end superficial, differences such as language and skin color, I instinctively knew how to work and live within that system, more than I knew, when I first arrived at the United States, how to feel at home in overstocked shopping-malls and supermarkets, or how comfortably or efficiently to operate within the highly regulated system called daily life in this country.

None of this is to say that when I am in Haiti, I am unaware of the regional context, or of the very real meaning my skin color holds there, and the position it grants me, whether I like it or not. I am aware, to speak fashionably, of a certain amount of privilege.

It is to say, however, that the position I enjoy in the Haitian context has neither been a constant in my life, nor has it defined my lived experiences, my identity, the contours of understanding I have of individual Haitians, or of the context they live in. When I am in Haiti, I am one of the people who, at the end of their stay, can take a plane and leave. The privilege of being able to choose where one goes is one that I am acutely aware of, perhaps precisely because growing up in Hungary, we were so grounded in a reality from which we could not easily escape. The liberty to leave is the most substantial privilege one can hold, regardless of one’s skin color, and this is a fact that my fellow travelers on the plane, mostly dark-skinned Haitians, also understand. It is an understanding that we share, one that my past, my own ‘white history’, makes very much possible.

Depending on context, home can mean different things. At one end of the spectrum, home is the place where one feels safe, supported and accepted, at the other, home is where one wants to flee from. In between, there is a wide variety. What connects these different notions of home is a sense of familiarity: ‘home’ is the place the workings of which you intimately and deeply know. Whether you embrace, challenge, or even reject your circumstances, you inhabit the conditions of your home.

4. Perspective, collectivity, and landscapes of singular stories

History, from the Eastern European perspective, is a chronicle of living on the receiving end of conquest and political oppression by various regional power players of a variety of skin colours. To invoke a fashionable lexicon, it is to be the subjects of Empire, to live on the margins, to be the subaltern, to constitute a buffer zone. There were the Mongols, and then there was the Ottoman Empire, which ruled the region for roughly two hundred years. The Ottoman Turks used to kidnap our children and use them as slave soldiers against their native country. At the time, it surely didn’t sound as evil as it sounds today. It was routine. A couple of centuries passed, the Nazis came, then the Soviet Union.

This is your history, I was told, the story of a nation that deserved better, because of its past suffering. My history, a ‘white’ history. Our history, a human story.

Am I a victim? Does this define me? Should it define me? Or is it time to move on? What do we do with the past? What would I have done if I had lived in one of those past eras of oppression? What does history look like when you’re living it, when you’re inhabiting it, when you marry and raise your children in it, when you look at it from the inside, from the bottom up?

People in Hungary lived with those questions. These questions surrounded us, shaped us, imprisoned us. It was our story, our history, our culture. A national tragedy. A regionally determined view of history.

Growing up I always knew that to talk about these facts was to state the obvious. They were common knowledge, part of our lived reality. Political violence, economic underdevelopment or mis-development, the fear of political authority, and a consequent sense of insecurity—these were daily facts of life for everyone. I grew up among stories of migration, displacement, of having to start over, both economically and emotionally, not only from zero, but from the depth of war-ravaged physical and mental landscapes. It was the routine course of individual lives for generations, including some lives presently in progress. It seemed to be our regional inheritance, diligently passed on.

Then I moved to North America where I became persuaded that talking about the facts and the ramifications of Eastern European history is not stating the obvious but is, rather, fundamentally necessary. What persuaded me was the growing popularity of the notion, always present in this country, that historical experience is quintessentially either ‘white’ or ‘black’. It’s necessary to talk about history so that we don’t forget the legacies and the injustices of countries hamstrung by notions of collective guilt, victimhood, and punishment dressed up as patriotism, national sentiment, historical redress, or struggle for a more just society. It’s necessary to talk so that we, in this country, can reconceptualize migration, oppression, survival, resistance, love, cruelty, despair, opportunism, and solidarity. It’s necessary to talk in order to give these universal features of human life a wider context, to see them as they flow through human stories, through places, through history. To recognize that they are embedded in the human condition, in our shared humanity. Perhaps then, by following their flow, we can truly reach Haiti and Hungary, and feel at home, no matter where we started from.

5. Official Press Release templates, United States, 2021

Presented without comment:

The University/company/our team continues to firmly stand against racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and discrimination of all kinds. We are actively encouraging our students/employees/team members to self-reflect and to educate themselves, to continuously learn from the experiences of others. Our goal is to make our campus/company a diverse, inclusive and vibrant community where members of marginalized communities feel recognized, safe and welcome. With that goal in mind, we are introducing the following guidelines/training programs to educate our students and staff/team members about injustices of the past and about ways to overcome them.

6. Diversity, inclusion, and maturity

Ever since Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2009 TED talk, it has been popular to refer to the “danger of a single story” in order to describe the influence of colonial oppression on the cultural experience and self-expression of subjugated peoples. Adichie’s words served as a moving description of the situation where unchallenged stories circulating in a community become prisons, rather than spaces of learning and discovery. Adichie was right about the danger of single stories repeated over and over again, and her suggestion to seek out and allow a variety of stories to stand is every bit as valid now as it was then.

Perhaps, alongside Adichie’s words, the following quotations will serve as counterpoint to our increasingly slogan-ridden, divided, and singularly focused discursive landscape. The quotations are, for me, invitations to connect and construct, as opposed to call out, dismantle and destroy. They inspire me to reflect and to learn, so we can all engage with wider historical perspectives as opposed to regionally defined ones and then move forward together to build a truly diverse home.

Here is Anne Applebaum, with whom this essay opened:

memories of the war could not be erased. Nor could the past easily be explained to outsiders who had not experienced the same level of destruction, and who had not witnessed the indifference human beings could show to one another’s suffering

Applebaum cites The Captive Mind, by Czesław Miłosz. In this 1953 work of non-fiction, the Polish Nobel Laureate wrote:

The man of the East cannot take Americans seriously because they have never undergone the experiences that teach men how relative their judgments and thinking habits are. Their resultant lack of imagination is appalling.

In What Killed Michael Brown, a documentary by director Eli Steele, the film’s writer and narrator Shelby Steele says:

The American story is much more a human story than a racial story. The original sin of this country is not slavery or racism per se, but it is using race as a means to power.

In a talk titled: Never Again, Refusing Race and Salvaging the Human, Paul Gilroy, a British academic who has written extensively on the cultural history of the Black Atlantic, argues:

races are not produced by nature, rather, they are conjured and created […] they are summoned as political actors. […] Identifications that emerge in opposition to a reified identity run the risk themselves of reifying race, place, gender, generation or sexuality. […] Cultural and social categories, such as the color-line, are historically contingent and it is useful to consider them historically, rather than metaphysically.

Connecting the words of Toni Morrison to the life of Primo Levy, Gilroy reminded his audience of Morrison’s “dogged refusal of a world definitively rendered in racialized shapes”.

Here is French-Rwandan author and singer, Gaël Faye, whose childhood unfolded against the backdrop of ethnic conflict and the Burundian civil war, in his autobiographical novel, Small Country:

“So where are you from?” A question as mundane as it is predictable. It feels like an obligatory rite of passage before the relationship can develop any further. My skin—the color of caramel—must explain itself by offering up its pedigree. “I am a human being”. My answer rankles with them. It’s not that I am trying to be provocative. Any more that I want to appear pedantic, or philosophical. But when I was just knee-high to a locust, I had already made up my mind never to define myself again.

Finally, a quotation which, no less than the others, motivated me to write this essay. It is from a 2021 New York Times bestseller. Titled The Rhythm of Prayer: A Collection for Meditations and Renewal, it is advertised as a resource “for the weary, the angry, the anxious, and the hopeful” that “offers rest, joyful resistance, and a call to act”. It contains a prayer by Chanequa Walker-Barnes, a psychologist and minister, who focuses on “healing legacies of racial and gender oppression”:

Dear God, Please help me hate White people. Or at least to want to hate them. At least, I want to stop caring about them individually, and collectively. I want to stop caring about their misguided, racist souls, to stop believing that they can be better, that they can stop being racist.

Walker-Barnes’ prayer expands on this theme as it goes along. I read, heard, and took in her prayer, and acted on its call. It served as an imperative to write, and to highlight better alternatives than hate, which, as history has shown, will divide us and make life precarious for us all.

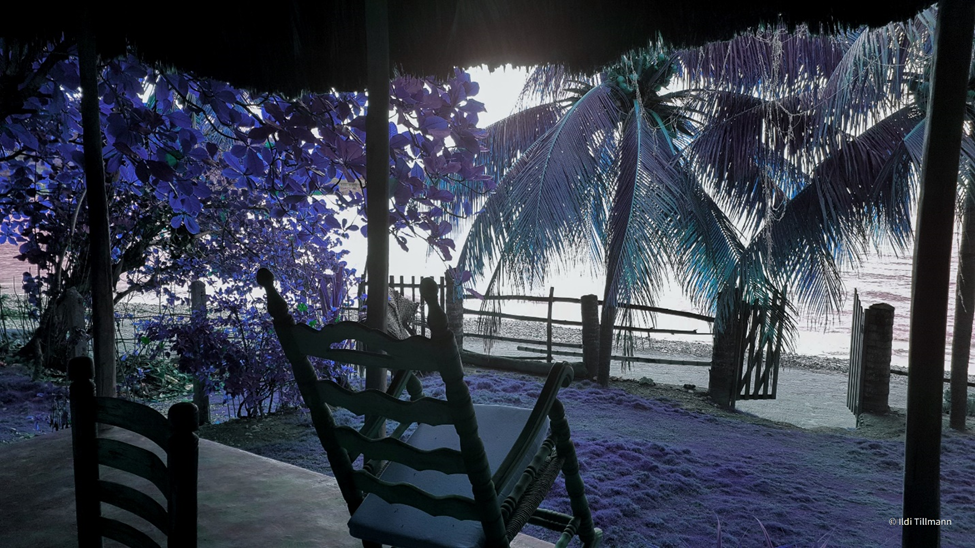

Ildi Tillmann is an author and photographer who has been working for the last three years on a freelance multimedia project in Haiti, titled Lives in Revolution. The project seeks to take readers and viewers behind news media headlines and beyond the pity-provoking stories and images of the nonprofit industry, two sources of knowledge production that are prevalent with respect to Haiti.

Selected images from Lives in Revolution won Honorable Mention at the International Photography Awards in 2020.

Prints of Ildi's Haiti photos are available through her website. Profits from sales of these photos will be shared 50/50 with the Haitian people with whom she works.

A reception for Ildi’s exhibit, Faces and Places – Beyond the Headlines, Haiti, will be held by the Africana Studies Department at SUNY, Stony Brook, on October 4, 2021.

To learn more about Ildi’s work, please visit her website, subscribe to her Medium page, and follow her on Instagram.

Beautiful essay.

TY (thank You), M. Tillmann. Will hafta reflect on this... Read again, and reflect somemore... TYTY.