Racist Voters and Rising Hate Groups

A Review of Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents," Part 1 of 2

Book Review

RACIST VOTERS AND RISING HATE GROUPS

A review of Isabel Wilkerson's Caste, Part 1 of 2

Nandini Patwardhan

Editors’ note: This is the first part of a two-part analysis of some of the most striking claims in Isabel Wilkerson’s 2020 book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. A follow-up post by the same reviewer will examine three additional claims the book makes about crime and policing.

I read Isabel Wilkerson’s book The Warmth of Other Suns soon after it came out in 2010. The descriptions of African Americans’ difficult journeys as they fled the Jim Crow South were gut-wrenching. As an immigrant, I empathized with their experiences of displacement and exile. It was heartbreaking to learn that they had been rendered despised migrants in their own country.

So, when I came across Wilkerson’s latest book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, I dove in. I expected to find new insights about the American racial divide. I found that and much else besides. Some of the statistics quoted in the book were so shocking that I looked for reputable sources that would confirm the underlying data and the inferences drawn. Here are the results of my investigations of just two of the book’s many claims.

I. Low support for Obama among white voters in 2008 and 2012?

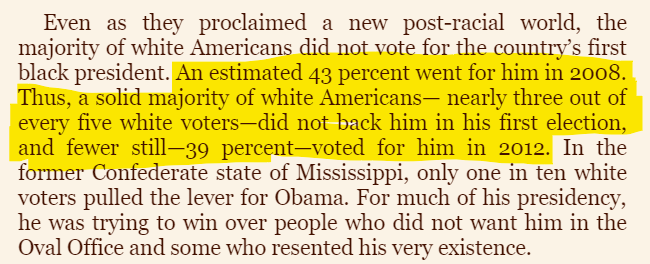

In a section of the book titled “Part Six: Backlash,” Wilkerson makes the claim that President Obama was elected with very little white support.

(p. 314)

(p. 315)

Summary:

It is worth noting that:

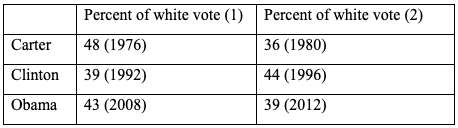

Obama did just as well with white voters in his second election as Clinton did in his first election.

Obama did better with white voters in his first election than Clinton did in his first election.

Obama did better with white voters in his second election than Carter did in his second election.

No Democrat (see just below) has come close to Carter’s 48% in the last four decades.

Lacking this important context, Wilkerson makes it sound as though white voters abandoned Democrats when Obama was running. But the two Democratic presidents who preceded Obama over the previous four decades also won relatively low percentages, that is, under 50%, of the white vote. So, it is a stretch when Wilkerson implies that a) Obama won an unusually low share of the white vote, and that b) this was because of white voters’ racist proclivities.

Given that Carter and Clinton were white, and Southerners to boot, I dug a little deeper into the percentages of white voters who vote for Democrat or Republican candidates, regardless of whether those candidates win or lose. The data present an enduring voting pattern dating back to the Carter era. Over the last four decades, the average white vote going to Democratic presidential candidates is 40.6% as opposed to 54.8% for Republican candidates.

This graph does not include the election of 2016, in which Trump got 57% of the white vote (one point below Romney in 2012), and Hillary Clinton got 37% (two points below Obama in 2012). And it does not include 2020, when 58% of white voters voted for Trump and 41% voted for Biden (two points below Obama in 2008). This confirms that, in both his elections, Obama fared about as well as white Democratic presidential candidates tend to fare (regardless of whether or not they win the election). In other words, contrary to the claims made by Wilkerson, the white electorate did not show any special anti-black bias in the two Obama elections.

The good news, which Wilkerson papers over because it does not fit her book’s doom-laden narrative, is that white voters are similarly inclined to pull the lever for Democratic presidential candidates regardless of the candidates’ color.

Moreover, it is worth noting that Democrats are not self-evidently the “party of non-whites.” For example:

“Since 2012, running against Trump twice, Democrats have lost 18 points off of their margin among nonwhite working class voters.”

A corollary is that Republicans are not self-evidently the party of whites. Biden won in 2020 because white working-class voters and white college-educated voters moved away from Trump and toward him (by 3 and 8 points, respectively). This shift of white voters to the Democratic candidate had the unexpected (many would say, welcome) effect of offsetting the non-white voters who shifted to Trump—working-class non-white voters by 12 points and college-educated non-white voters by 7 points.

In summary, presidential elections are not referenda on voters’ racism. Using the data selectively to suggest that voters were particularly racist during the two Obama elections and interpreting this as evidence of a backlash against Obama’s blackness is incorrect, and worse, unnecessarily catastrophizing and divisive.

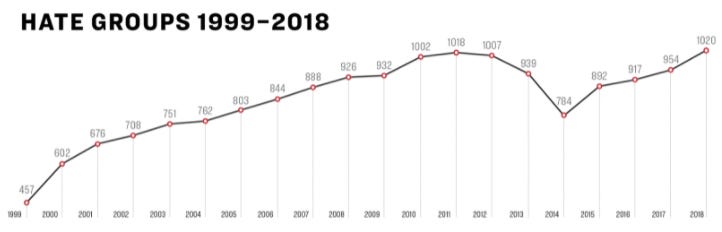

II. A rise in hate groups during Obama’s presidency?

The “Backlash” section of the book goes on to claim that the number of hate groups increased substantially during President Obama’s term in office, the implication being that this was a reaction to his blackness.

(p. 319)

It seems odd that the author quotes the Southern Poverty Law Center’s hate group statistics for the period 2000-2010, considering that this covers only the first two years of Obama’s eight years in office. Why not examine a broader period with greater overlap? After all, Caste was published in 2020.

At the very least, the book could have included data available in a 2015 article in the Washington Post that shows hate groups declining from 2011 to 2014. Or, as I have done here, the book could have included the Southern Poverty Law Center’s most recent data, from a 2019 article:

The chart makes several things clear:

The number of hate groups rose steadily from 2000-2010. Only two of these eleven years overlap with the Obama administration. So, it is misleading to imply that a significant rise corresponded with the early Obama years.

The number of hate groups was essentially flat from 2010-2012, which was the second half of Obama’s first term.

In the first half of Obama’s second term, the number of hate groups began falling and by 2014 was back to the 2004-2005 level.

By the end of Obama’s second term in 2016, the number of hate groups was where it had been at the beginning of his first term, in 2008.

In other words, the net result of the first black president’s two terms was that the number of hate groups flat-lined.

It is worth noting that hate groups again rose under Trump, continuing their steady, two-decade-long increase, and they reached their highest numbers on record in 2018. While this is undoubtedly unfortunate, it should not obscure the good news that there was no overall, out-of-pattern uptick in the number of hate groups during Obama’s terms compared to the decade before he took office.

Once again, Wilkerson’s selective use of data to present a catastrophizing and inaccurate picture of the country is very disheartening.

What is the significance of these analyses?

Words like “truth,” “fairness,” “accuracy,” “objectivity,” and “rationality” are not just lofty words to be invoked when convenient. They are foundational ideas on which is built the edifice of our society. When these ideas are treated as disposable or inconvenient, it is a setback not just for the individuals and institutions in question, but for our society as a whole.

I am an immigrant who has put down roots in this country. I willingly gave up a lot and risked a lot. As a grandmother, I care deeply about the kind of country my grandchildren will inherit. Through the years, I tried to do my part to understand my adopted country’s complicated history and to support my most beleaguered fellow citizens. Reading accounts like the ones I analyzed above made me feel demoralized—not only that there has been little or no progress, but that there is little likelihood of it.

When my deep dive into the data refuted the bleak picture Wilkerson paints, I actually felt heartened and optimistic. My hope is that readers will also find reason to feel more rather than less hopeful about the direction of the moral arc of our country.

Stay tuned for the second part of my analysis of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste.

Nandini Patwardhan is originally from India but has now lived in the US for four decades. She is a retired software engineer and a passionate nonfiction writer, whose work was awarded the San Francisco Press Club Award in 2020 and 2021. Her 2020 biography of Anandi Joshee (1865–1887), titled Radical Spirits: India's First Woman Doctor and Her American Champions, won the Benjamin Franklin Award in Biography. Nandini lives in Oakland, CA. Follow her on Twitter and visit her website.

Whenever I read something which starts out generally along the lines of “all back people” or “all Hispanic people” or particularly “all LGBT” people, I brace myself to discount most of what is being said because writers frequently, possibly intentionally confuse or misinterpret correlation with causation. I remember laughing out loud when a friend started chatting about the dearth of Black Olympic swimmers and wondering about their specific gravity compared to white people. I said “reconsider your question by family economic status and you’ll see immediately what’s happening”.

I wish we could start speaking more about economic class than race, because while race is intrinsically non-quantifiable, economic class is. What is Jewish? What is Latino? What is Asian? What is “mixed race?”

Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio - what race is he? Enrique is not wealthy. What race is Tiger Woods? Tiger Woods is extremely wealthy. What’s the real issue?

The Southern Poverty Law Center in its name best targets the most pressing issue, systemic multigenerational economic disadvantages.

The book also casually gets WEB Du Bois’s birthplace wrong, listing it as Amherst when he was born in Great Barrington. This is a pretty trivial error but made me wonder: “if they didn’t even fact check that, what, if anything, did they fact check?”