Race/racism

THE TOGETHERNESS WAYFINDER

Learn to be a raceless antiracist

Sheena Michele Mason

Our common country is the United States. Here were we born, here raised and educated; here are the scenes of childhood; the pleasant associations of our school going days; the loved enjoyments of our domestic and fireside relations, and the sacred graves of our departed fathers and mothers, and from here will we not be driven by any policy that may be schemed against us.

That very little comparatively as yet has been done, to attain a respectable position as a class in this country, will not be denied, and that the successful accomplishment of this end is also possible, must also be admitted; but in what manner, and by what means, has long been, and is even now, by the best thinking minds among the colored people themselves, a matter of difference of opinion.

—Martin Robinson Delany, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852)

Our traditionally accepted methods to end or at least resist racism racism through color-consciousness and colorblindness in the United States have taken us as far as they can. We need a fresh framework to help us create a future without racism. In my forthcoming book, The Raceless Antiracist: Why Ending Race Is the Future of Antiracism (October 2024), I present the togetherness wayfinder as just such a framework. Here, I give a brief overview of why we need new methods for what we have come to call antiracism and the other side of the same coin that we call colorblindness and a very brief overview of what the togetherness wayfinder offers in the wake of both responses to racism, particularly antiblack racism.

Preorder between now and October 17th on Tertulia with code SHEENA to save 25%

The togetherness wayfinder is composed of concepts, philosophy, language, information, tenets, and the racelessness translator. In its entirety, the wayfinder helps us navigate toward a future free of the causes and effects of racism today.

Here are the core tenets and definitions of the togetherness wayfinder:

1. Race/ism (i.e., racism) is a socially constructed system of economic and social oppression that requires the belief in human “races” and the practice of racialization to reinforce various power imbalances.

2. “Race” is an imaginary component of the socially constructed reality of race/ism.

3. Racialization is the process of applying an inescapable economic and social class hierarchy to humans that creates or reinforces power imbalances.

4. Belief in human “races” and practice of racialization affect people differently, giving power to some and disempowering others. These differences serve to uphold the machinery of racism, acting as obstacles to unification, healing, and reconciliation.

5. Translation of what one means by “race,” including the presumed absence of “race,” can lead to understanding and bridge-making. The racelessness translator helps people interpret “race” into something being said about culture, ethnicity, social class, economic class, the causes/effects of racism, or some combination thereof.

6. Race/ism does not exist everywhere in the same way and can be ended.

The primary tool of the togetherness wayfinder is the racelessness translator, which allows us to translate that which is perceived or presumed to be about “race” or “racial” or the absence of “race” into more apt and precise language. Specifically, when we talk about “race,” we are typically talking about one of five other things—culture, ethnicity, social class, economic class, or racism itself—or some combination thereof. By properly translating “race” into culture, ethnicity, and so on, we expose the reality of what we mean. This increases shared understanding and clarity about racism and other aspects of humanity. It lays bare the reality of racism and enables us to imagine and create a different and better future for all. This is not a matter of mere semantics or rhetoric. It is a matter of recognizing human-made systems of oppression and choosing to forge a better path forward for all of us without race/ism.

The other tools of the togetherness wayfinder include what I refer to as architecture, the walking negative, rememory, Ubuntu, creolization, opacity, marronage, maternal energy, invisible ink, twilight, madness, consolation, nation, diaspora, home, and philosophies of “race” that are seldom taught and commonly misconstrued. When best understood, the wayfinder allows for more astute identifications of what racism is and isn’t. It also allows us to determine what will and won’t work to stop racism and its ill effects in their tracks. Further, the togetherness wayfinder opens the door to a better understanding of culture, ethnicity, nation, humanity, and so on.

In the U.S. and elsewhere, the continuing policy of upholding the belief in “race” and the practice of racialization help to maintain the dehumanizing effects and material impacts of racism or race/ism, as I often write it. But we cannot simply “skip to the good part,” as Morgan Freeman and many others suggest, and merely stop talking about race. Instead, we need to navigate carefully and strategically to bring to fruition a better future for all versus hiding and ignoring real problems.

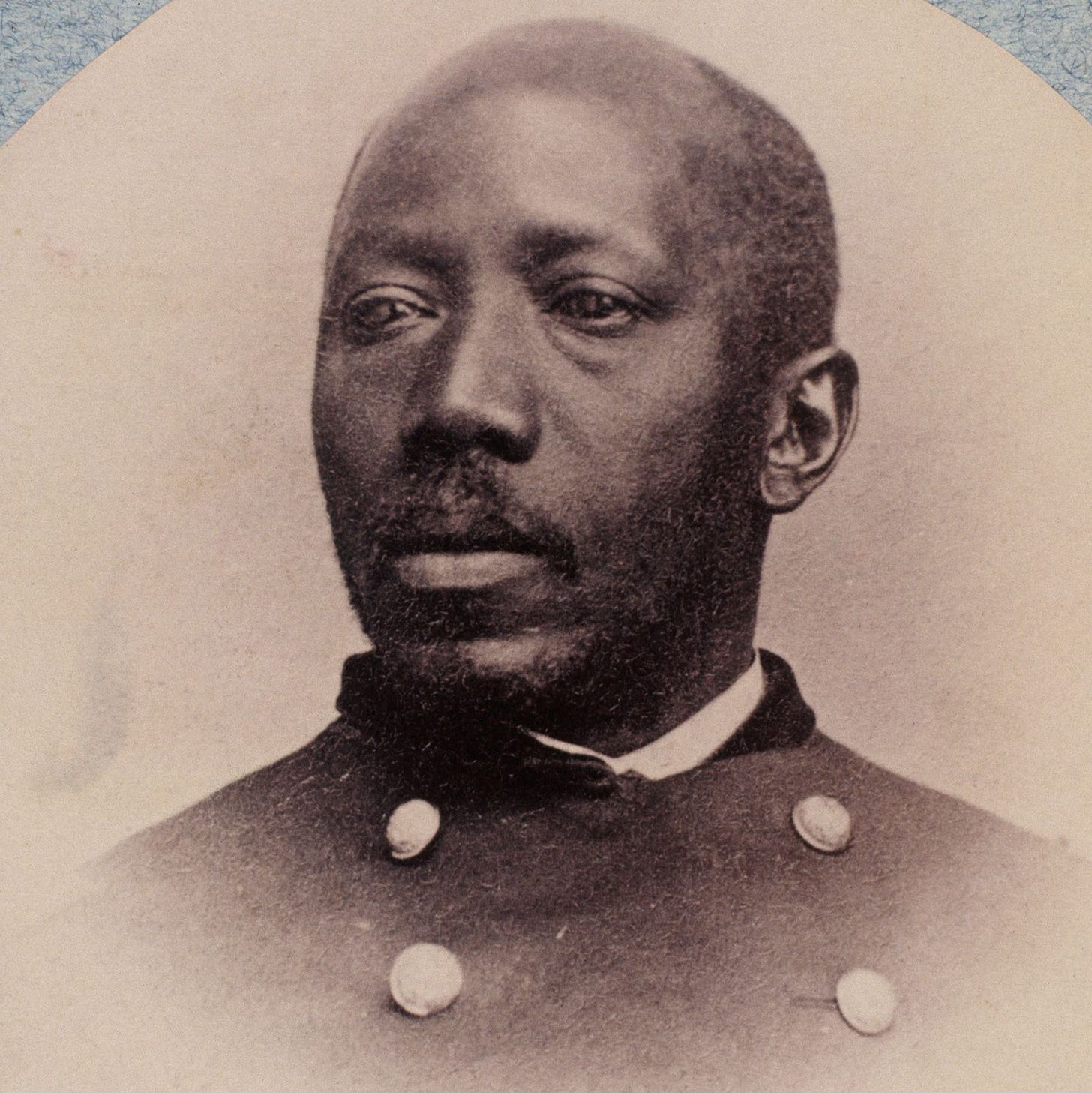

Over the centuries, many people have written about the topic of “race” and the history of race/ism, especially antiblack racism. In 1852, Martin Robinson Delany, an American abolitionist, journalist, physician, military officer, and writer who is credited by some scholars as the first proponent of black nationalism and for coining the Pan-African slogan “Africa for Africans,” wrote that Americans of more recent African descent were not enslaved because of actual or perceived inferiority. Rather, he rightly argued that enslaving Africans and their more recent descendants enabled wealthy Europeans and their more recent descendants, who got racialized as white within the antiblack paradigm, to maintain and increase their wealth, economic, political, and social power.

The ideology of inferiority through the belief in “race” and practice of racialization came after the machinery of humanmade social, political, and economic hierarchical constructions were already on the ground. The ideology came into being to justify the unequal economic, political, and social arrangement. Abolitionists like Delany sought to end chattel enslavement and other forms of enslavement around the world. They often did so while operating within the belief in “race” and practice of racialization that they were born into. And abolitionists who got racialized as white reinforced that method of activism, which helped to maintain the white supremacist paradigm. That is especially true the further back in time one goes, since humans had not yet developed the science of humankind enough to know that “race” is not biological and that there is no “essence” to “race.” Most people before the 1900s believed that “race” was, indeed, biological. Delany was no exception.

But that belief in biological “race” and the practice of racialization was steeped into the fabric of American society largely as a Trojan Horse, a decoy of sorts. Its purpose was not scientific. Its design was not to enlighten or act as a neutral descriptor. Neither “race” nor the practice of assigning “race” to the human species is arbitrary, as in not based on any principle, plan, or system. Rather, the belief in human “races” and the practice of assigning “races” to the human species is designed simultaneously to reflect and to maintain the reality of race/ism. Like abolitionists seeking to end enslavement while still endorsing the belief in human “races,” to continue to strive to create a future without racism while maintaining the components required for its survival is like trying to stop a flood by dousing it with water.

In The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852), Delany shows how the ruling class—that time’s elite—demarcated Africans and Americans of more recent African descent as fit for subjugation in all realms of life, whether they were enslaved, freed, or maroons. Africa represented an entire continent of people that Europeans-turned-Americans could exploit for labor. Those Europeans, and then early Americans, needed an ideological apparatus—a system—that would ensure the success of the social, political, and economic hierarchies they started and desired to maintain and continue to develop.

The belief in and illusion of “race” and the practice of racialization became necessary components of that early hierarchical system, one that spanned all facets of life. (Refer back to how racism or race/ism is defined within the wayfinder.) Delany writes, “It is not enough, that these people [Africans, and then enslaved Americans] are deprived of equal privileges by their rulers, but, the more effectually to succeed, the equality of these classes must be denied, and their inferiority by nature as distinct races, actually asserted. This policy is necessary to appease the opposition that might be interposed in their behalf” (Chapter I). That economic, social, and ideological system is one that remains in various forms, albeit without chattel enslavement. That does not make it any less pernicious or subterranean.

“Race” is caught up with how one thinks about the human. Our belief in human “races” and practice of racialization determine who gets dehumanized in practice and action and why and who has power and why, as evidenced by the history of colonization, chattel enslavement, a failed Reconstruction, Jim Crow, de facto segregation, and so on. In places like the U.S., “race” often gets conflated and collapsed with ethnicity, culture, social and economic class, and as evidence of the causes and effects of racism itself. But that conflation hinders our ability to effectively create pathways toward a future without race/ism. If we let it, the togetherness wayfinder can lead us toward a future where every human is rightly humanized and humans are seen as commonly biological alongside all other beings. Our responsibility to all life on Earth gets too easily deferred by other looming power imbalances to the detriment of all life.

How the “human” has been constructed has been to distinguish humans from animals and to distinguish some humans from seemingly human humans, who are really more like animals, or are fully animal. But if we cut through the racist imaginings of how the supposedly “sub-human” or “nonhuman” human behaves, we see that all of what makes us human includes all of what we tend to assign to “monsters,” “animals,” and other supposed “nonhumans.” So long as we continue to lie to ourselves, we will also continue to endanger those populations deemed inferior and all biological life on earth. And the efforts of Delany and other abolitionists will continue to fall just short of complete liberation and the end of antiblack race/ism.

When engaged and practiced, the togetherness wayfinder helps people free themselves from binary modes of thought as it pertains to social identities and overlapping and interlocking systems of oppression. That freedom translates into

1. a clearer understanding and identification of economic and social systems of oppression;

2. an expanded conception of the human, culture, ethnicity, social class, economic class, and racism;

3. a mode of seeing and being that lessens the internalization of racism-induced traumas;

4. an internalized method of ending the causes and effects of racism that manifest from within individuals and desiring the end of the causes and effects of racism externally (i.e., structurally, collectively, etc.).

Let us turn again to Delany, who writes,

Moral theories have long been resorted to by us, as a means of effecting the redemption of our brethren in bonds, and the elevation of the free colored people in this country. Experience has taught us, that speculations are not enough; that the practical application of principles adduced, the thing carried out, is the only true and proper course to pursue. (Chapter V)

To date, racist, antiracist, and colorblind theories have been, to use Delany’s language, “resorted to as a means of effecting” the abolition of racism. However, the practical application of these theories cannot bring to fruition the change that Delany envisioned, because they all include and require the very components of the apparatus that they seek to eradicate, namely, a belief in “race” and the practice of racialization.

It is necessary to take an abolitionist position toward racism and, by extension, the belief in “race” and practice of racialization. Rather than seek the abolition of the symptoms of race/ism we must seek to abolish its roots. To do any of that, we need a strategy and toolkit. It bears reiterating that we cannot skip to the good part if we are sincere about creating change, which is where the togetherness wayfinder comes into play. The wayfinder includes and requires more of us than a simple agreement about the perniciousness of race/ism and a desire to end it. Instead, we need to enrich and revitalize how we strive to accomplish such a worthwhile and just goal by imagining and implementing more effective approaches that do not merely serve to maintain the status quo. Only then will the economic, social, and political power imbalances that exist and persist thanks to the human capacity to dehumanize humans in favor of exploitation and domination be abolished in turn.

Sheena Michele Mason is Assistant Professor of English at SUNY Oneonta. She holds a Ph.D. with distinction in English from Howard University in Washington, D.C., and specializes in Africana and American literature studies and philosophy of race. She is published with Oxford University Press, Palgrave MacMillan, Cambridge University Press, and the University of Warsaw Press, among others. She is the innovator of the togetherness wayfinder (formerly and alternatively called the theory of racelessness) and founder of Togetherness Wayfinder, an educational firm. Her book The Raceless Antiracist: Why Ending Race Is the Future of Antiracism shows how ending our belief in “race” and the practice of racialization is required if we aspire to end the causes and effects of racialized dehumanization.

This is fascinating. I'll have to read the book when it comes out. There's a large and well-funded industry of identitarian politics that is going to oppose anything along these lines, but you must surely know this already, so I commend your willingness to undertake an effort like this.

Ah, Sheena, I am so looking froward to your book. You clearly have continued growing in intellect and spirit, finding the language at just the right time to penetrate the fog.