Travis McMichael Pulled the Trigger

But Georgia’s Broken Mental Health System Put Ahmaud Arbery in the Line of Fire

Investigative report

TRAVIS McMICHAEL PULLED THE TRIGGER BUT GEORGIA’S BROKEN MENTAL HEALTH SYSTEM PUT AHMAUD ARBERY IN THE LINE OF FIRE

By the Editors

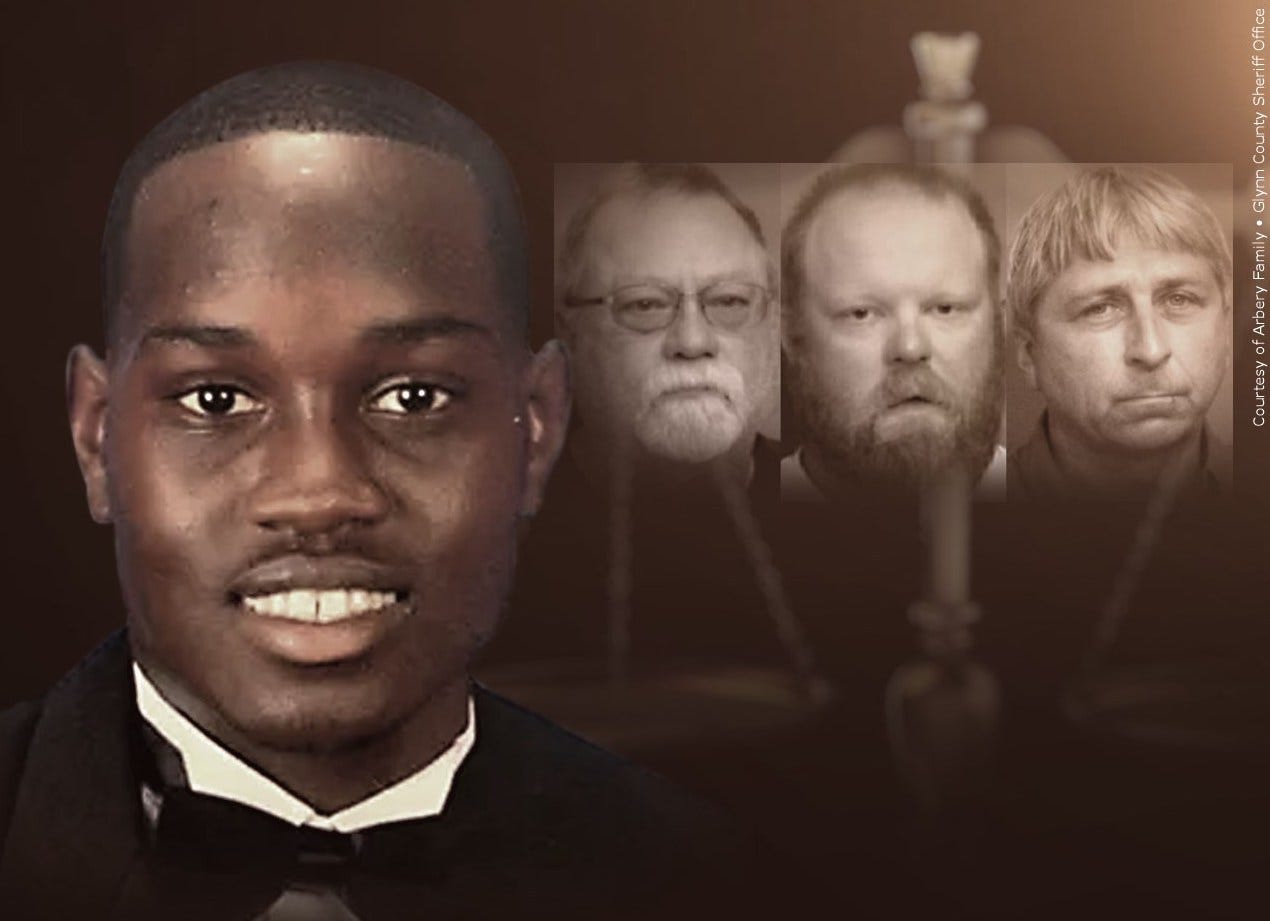

After almost two years, the family of Ahmaud Arbery has received justice. Three men who chased down the 24-year-old jogger in their pickup trucks—emboldened by Georgia’s slave-era “citizen’s arrest” law that dates to 1863—before killing him with a shotgun, were found guilty of murder by a jury last Wednesday after ten and a half hours of deliberation. While the media narrative around the trial almost universally focused on the race of the victim (black) and defendants (white), race didn’t enter into the criminal trial itself. Race will be the central issue, of course, when Travis McMichael, his father Gregory, and their neighbor William Bryan face federal hate crime charges in three months.

More will come out in federal court, but we’d like to suggest in this article that personal racism is merely part of the story. Arbery suffered from grave mental health problems that plausibly played a role in his repeated encounters with the law (and on one occasion, with Travis McMichael) in the years leading up to his death. Let us note immediately what the previous sentence is not saying: it’s not saying that it was somehow “understandable” let alone “justified” that the McMichaels tracked down and murdered Arbery. Our purpose in this post is neither to blame the victim nor to suggest that his mental illness or behavior exonerates the defendants and their treatment of him.

Rather, our contention is that at every turn, Georgia’s various public systems failed to provide Arbery the help that he needed, help that would almost certainly have spared him his last fatal encounter with his murderers. This article does not represent an exhaustive investigation, which we have not had the time or resources to conduct. Rather, it represents our careful reading of publicly available but apparently little-studied documents—all linked at the end of the article—and the inferences we have drawn and questions we think need answering as a result.

Most who’ve followed the tragedy are probably aware Arbery had mental health issues, but not much detail has been reported. A laconic reference can be found in a June 4, 2020 (updated November 5, 2021), story in the New York Times, which quotes Richard Dial, assistant special agent in charge for the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, in his testimony to Glynn County Magistrate Court:

Mr. Arbery had a mental illness that caused him to have “auditory hallucinations.” He said Mr. Arbery was not being treated for that illness on the day he was killed.

This passes by quickly, and though several other outlets named the disorder, it’s difficult to find a fuller account anywhere in mainstream reporting. Even last night’s 20/20 episode barely mentions it. Yet a review of pre-trial filings and proceedings not admitted in court (Chatham County Superior Court and United States District Court for the Southern District of Georgia) reveals a series of missed opportunities by local law enforcement and mental health providers to intervene.

Georgia’s public mental health systems allowed a young man with schizoaffective disorder—a debilitating condition involving symptoms of schizophrenia and mood disorder—to go untreated. This disorder caused Arbery to hear voices urging him “to rob and steal”and “to hurt people.”Regardless of this serious condition, Arbery was left to wander the streets of Brunswick, Georgia, at night, past his probationary curfew, and off his antipsychotic medication (Zyprexa), for a year and a half without meaningful intervention. On one occasion, Arbery’s untreated condition left his own mother so frightened she called 911, warning the dispatcher that his mental illness might lead him to become violent with responding officers. These systems failed to help a young man who was in no condition to help himself. These systems failed to help a family that had reached the end of its resources for dealing with an unwell son.

From court filings, we know that during the year and a half before his murder, a mentally-ill Arbery trespassed on multiple residential properties, removed screens and attempted to enter windows, entered a house and a trailer, stole items from nearby convenience stores, ran from people who approached him, and issued violent threats to responding police officers and even to one of his eventual killers, Travis McMichael. In all these cases, police—who by June 2018 knew that Arbery had mental health issues and was prone to violence—declined to arrest him. To be clear, it is possible that the police declined to arrest him because to do so would have resulted in Arbery’s felony probation being revoked and his serving at least a year in jail. Many police and others who work in the criminal justice system know that people with mental illness should, when feasible, be kept out of jail and prison, where they are likely to be victimized by other inmates.

It was no secret that Arbery was in trouble and that his family was trying to help him. By the time Arbery’s mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, called 911 in June of 2018 from her car, telling the dispatcher that her son refused to give her the car keys, and warning that his mental illness, which had “escalated,” might lead him to become violent with officers, Arbery was already on felony probation for carrying a gun on school property and three counts of felony obstruction of an officer. His mental condition was also deteriorating. In her interview with federal investigators, Cooper-Jones explained that, in 2018, she reached out to Arbery’s probation officer for help, telling him she “didn’t recognize” her son, who’d become a “different young man,” and lamenting that she “couldn’t fix” the problem by herself. She told federal investigators she'd become “fearful of him, myself,” and that Arbery began to run obsessively, which staff at Gateway Behavioral Health, the community-based provider that diagnosed his disorder, explained might be a self-comforting or calming behavior related to his mental illness. The picture of Cooper-Jones that emerges from the interview is one of a concerned, involved mother, dedicated to her son’s well-being, at her wits’ end, unable to find the resources she needed.

We’ve already noted that the police who interacted with Arbery did not arrest him. Neither do they appear to have attempted to redirect him to mental health services. At least, he seems not to have returned to Gateway for further treatment. It may be relevant here that Arbery was unemployed and likely did not have medical insurance, a state of affairs that could have left him reliant on publicly-funded systems like Gateway. It is also relevant that Georgia refused to expand Medicaid under the ACA, and so probably had limited public resources to offer someone in Arbery’s situation (more on Georgia’s mental health care funding below). Moreover, it appears that Arbery’s probation officer—a profession that is famously overworked and underpaid—failed to respond to Arbery’s mother’s desperate pleas. It appears that the probation officer did not, for example, insist that Arbery continue to visit Gateway. Finally, it appears that there was no public intervention available for Arbery—not from the police with whom he interacted, not from his probation officer, not from any other agency—when he discontinued his antipsychotic medications.

The Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities coordinates with community-based providers like Gateway to provide adult mental health programs, including Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), which could have provided Arbery with 24/7 psychiatric support, and Intensive Case Management (ICM), which could have, presumably, helped ensure he took his meds. Such programs are called, generically, “diversion programs.” Though we don’t know how Georgia or Glynn County administer such programs, if Arbery had qualified, or, indeed, if he’d been enrolled in one at the time of his murder, there are standard ways that these diversion programs motivate adherence:

Mental health treatment could be a condition of bail, permitting the defendant's release without the need to post money, or could be a condition of probation, allowing a defendant to avoid a county jail or state prison sentence.

Arbery, for whatever reasons, discontinued his treatment. No one from Gateway seems to have reached out to him after providing the initial diagnosis and prescription. And law enforcement (including his probation officer) was apparently unable to motivate him, but was also unwilling to arrest or incarcerate him.

Here’s why it matters: young men suffering from mental illness, especially young black men, are highly likely to be seen as a threat. And young black men are the least likely to receive treatment. This confluence leaves young mentally ill black men, like Arbery, especially vulnerable to violence from police and from vigilantes like the McMichaels and Bryan.

While it is too late for Arbery, we should demand further investigation into the issues we’ve raised here, so we can understand in detail the ways in which the system failed (or, perhaps in some cases, did not fail) Arbery and his family and then do something to ensure that other struggling individuals, especially disadvantaged ones, don’t suffer a similar fate.

The sort of case that Arbery presented to police in his several encounters with them has been studied and has a playbook of recommended steps associated with it. According to the Council of State Governments’ Justice Center (which coordinates with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance), “high utilizers,” like Arbery, “are typically well known to law enforcement agencies and many times have serious mental health concerns, substance use disorders, and other significant health and social service needs.”

CSG/BJA advises law enforcement leaders to

design and implement response options that can divert these individuals away from arrest and ensure follow-up care coordination and connection to community-based supports. These partners should include leaders from the health and social service systems, as well as groups in the community who represent advocates, consumers of mental health services, and their families. [Emphasis added.]

Such recommended care coordination was evidently not available to Arbery or his mother. If so, it is likely still not available to other mentally ill “high utilizers” in Georgia, either. The Savannah Morning News reported in 2020:

The Georgia Sheriffs’ Association said that … many people with mental illness [are] being locked up in jails even though they have not committed violent offenses.

“They don’t need to be in jail, but there’s no place to take them. It’s very frustrating,’’ says Bill Hallsworth, jail and court services coordinator for the Sheriffs’ Association. “A lot of them are good folks but they have a hard time getting along in the community.’’

“The jails have become the de facto biggest mental health facility’’ in the state, Hallsworth adds.

Mental health spending in Georgia is far below the national average (according to Ted Lutterman, Executive Director/CEO of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute):

“The state spent $60.25 per capita (based on 2015 figures), ranking 44th among states, and spending far lower than the national mark of $109 per capita.”

The Georgia General Assembly and the governor should be called to account for this. As we noted at the outset, analysis of the tragedy that limits itself to the personal racial animus of the defendants (or for that matter of the residents of the Satilla Shores neighborhood) and their actions is not enough. The McMichaels and Bryan behaved abominably. There is no excuse for what they did, and they are being duly punished. But in our justified indignation at the guilty men, we must not neglect to address the structural conditions that left a young man who was struggling with a dangerous and debilitating illness vulnerable to being victimized, despite having a loving and attentive mother, a diagnosis, and prescribed course of treatment. To focus only on the guilty men or on their racism is to ignore structural problems in public mental health provision—not only in Georgia but across the country. These structural problems guarantee that people suffering from mental illnesses will continue to fall through the cracks and end up harmed in one way or another. Disproportionately, these are likely to be people like Arbery from disadvantaged backgrounds, whose families simply cannot afford expensive private care. As Mahatma Gandhi once said, “The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.” We should strive to measure up.

Pre-trial filings referenced

https://www.glynncounty.org/DocumentCenter/View/72461/11421-Addendum-to-def-brief-in-support

https://www.glynncounty.org/DocumentCenter/View/69162/114-Notice-of-Intent

I fear those involved with Aubrey’s mental health case, the moment they heard of his demise, exclaimed “Oh, sh**” because they all but knew how he died.

Another sad case of a faceless bureaucracy unaccountable for its malfeasance.

Wow, this is not something I had heard about before and it makes the case all the more heartbreaking and enraging. As someone with a sibling who has paranoid schizophrenia this hits very close to home. Our society is failing the mentally ill and it is depressing as hell.