Was American Slavery Unique?

The roots of chattel slavery and the myth of American exceptionalism

Slavery

WAS AMERICAN SLAVERY UNIQUE?

The roots of chattel slavery and the myth of American exceptionalism

Justin Suran

In her widely read introduction to The 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones declared that slavery in the United States was “unlike anything that had existed in the world before.” The truth is that chattel slavery in the United States had many features in common with other slave systems throughout world history. Chattel slavery and ethno-racial inequality were deeply intertwined long before the slave ship White Lion sold “20. and odd” African captives to colonial Virginians in 1619. The British colonies and later the United States were participants in a transcultural system of exploitation and forced labor rooted in the ancient and medieval past and pervasive throughout the Atlantic world by the 1600s.

Different types of slavery have been practiced over the course of human history. Historians usually distinguish chattel slavery from other forms of unfree labor (such as serfdom) and other forms of slavery (such as debt slavery). Chattel slavery—the kind that once existed in the United States—treats the enslaved person as an item of property, an object to be bought, sold, or given away.

Chattel slavery originated in ancient Mesopotamia and is as old as written history. The 4000-year-old Laws of Eshnunna included slaves among the objects that could be bought or sold, such as “an ox or any other purchase.” In Sumerian societies, the sale of chattel slaves was recorded on cuneiform tablets. Around 1750 BCE, King Hammurabi of Babylonia wrote some of the earliest laws on slavery. According to the historian Muhammad Dandamaev, “Babylonian slaves of the seventh to the fourth century [BCE] . . . were the absolute, unconditional property of their owners.” The Code of Hammurabi stated that any slave who “[struck] the body of a freed man” or “[said] to his master ‘You are not my master’” would lose an ear. Slaves were tattooed or branded to signify ownership, and runaway slaves had to be returned to their owners. The penalty for harboring a runaway was death.

Moreover, the association between chattel slavery and hereditary status dates back to these first civilizations. “The children born to slaves in early Mesopotamia,” writes John Nicholas Reid, “were another commodity that could be bought and sold.” In the process of being sold, an enslaved child could be separated from his or her mother. Heather D. Baker estimates that the majority of slaves owned by elite families in Babylonia were born into slavery. Enslaved children began to work around the age of five.

Mesopotamia was thus the cradle of chattel slavery. But later societies would make even more extensive use of slave labor. The earliest of these “slave societies” (or “slave economies”) was classical Greece. Estimates of the slave population in Athens range from 15 to 35 percent of the total population. Athenian slaves worked as domestic servants, agricultural laborers, and craftsmen, making everything from household furniture and musical instruments to military shields and blades. In the silver mines, slaves worked in chain gangs, often to the point of death. In The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 1, The Ancient Mediterranean World (2011), Tracey E. Rihll sums up their importance: “In the home, in the market, in the workshop, on the farm, slaves accompanied Athenians from cradle to grave, putting food on the table, wine in the jar, clothes on their backs and money in their hands.”

In classical Greece, as in the United States, political and economic freedom developed alongside slavery. In the city-state of Athens—the birthplace of democracy—chattel slavery enabled Athenian citizens to participate in the political process. The philosopher Aristotle argued that there was no contradiction between slavery and democracy: some people, especially non-Greeks, were “slaves by nature,” lacking the highest forms of reason required of citizens. Slaves could not participate in Athenian assemblies and courts. Nevertheless, slaves owned by the city-state performed public functions in Athens. They were what we today call civil servants: court clerks, accountants, even security forces.

The Greeks enslaved mostly non-Greeks, whom they viewed as primitive and inferior. Some slaves were captives of war, but most chattel slaves were acquired by way of trade in the Aegean and Black Seas. Slaves were imported from such places as Southeast Europe, Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and the Eastern Mediterranean. There was a thriving slave trade throughout the region, and the Greeks had access to its markets. According to David Braund’s chapter, “The slave supply in classical Greece,” in The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 1, The Ancient Mediterranean World (2011), “The slave trade was everywhere. At the periphery of Greek culture, slaves were traded all around the Black Sea, in the Adriatic and in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. So too at its traditional centres—in Athens, Aegina, Corinth, Chios and elsewhere.”

Like the Greeks, the Romans made extensive use of chattel slaves. Slavery was critical to the Roman economy and to the expansion of the empire. It’s conjectured that between 10 and 20 percent of the Roman Empire’s population was enslaved. Moreover, the Romans and the Byzantine Empire expanded chattel slavery geographically into Africa, particularly in North and Northeast Africa.

By this time, Africans had created their own indigenous forms of slavery. However, little is known about these indigenous slave systems before the the early seventh century and the start of the Islamic slave trade. Slaves from the interior of the continent were traded through the Kingdom of Da’amat in Ethiopia as early as the seventh century BCE. Later, the city of Aksum (also in present-day Ethiopia) became an important hub of the slave trade. Other slaveholding kingdoms developed in West and Central Africa.

From the 600s through the 1800s, an estimated 11-17 million Africans were forced into the Islamic trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean slave trades and sold in places such as Cairo, Baghdad, Istanbul, and Mecca. Islam did not permit the enslavement of other Muslims, so slaves were obtained by raiding or trading with other societies. Africans were used throughout the Islamic world as agricultural laborers, domestic workers, soldiers, and concubines. Ghanian kings benefited from their location between North Africa and West Africa, where the trans-Saharan trade included salt, copper, gold, and slaves. In 1324 Mansa Musa—the Muslim ruler of the Mali Empire and one of the richest men in the world—famously led a caravan to Mecca including thousands of slaves dressed in brocade and silk tunics.

What today we call “race” was central to the dynamics of slavery in the medieval world, although the modern race concept did not emerge until the late 1600s. Early and medieval Christian writers equated black skin color in general and Africans in particular with monstrosity and sinfulness; similarly, Muslim scholars and Arab slave traders linked color and culture and propagated racist ideas about black inferiority. In the Muqaddimah (1377 CE), the Arab scholar and historian Ibn Khaldun wrote: “the Negro nations are, as a rule, submissive to slavery, because [they] have little that is [essentially] human and possess attributes that are quite similar to those of dumb animals.”

Recent scholarship has emphasized the significance of race in the Islamic slave trade. In one famous revolt, black slaves from East Africa (the Zanj) rose up against their Arab slave masters in the Abbasid Caliphate. For fourteen years (869-883 CE), the Zanj and their supporters conducted a “racialized” rebellion, raiding towns, seizing weapons, and freeing slaves. They captured the city of Basra and came within seventy miles of the Abbasid capital, Baghdad. Ethno-racial distinctions between Europeans and Turks or Europeans and Berbers were also clearly demarcated. European as well as African slaves were held within the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire for hundreds of years. In one famous story, the Englishman John Smith was captured in battle and sold to a Turk before he escaped enslavement and helped colonize Virginia in 1607. The Barbary pirates, who were mostly Muslims operating from North Africa, raided Europe’s coastal towns and merchant ships and sold those whom they captured into slavery. The term “white slavery” was used to describe the European Christians held as slaves along the Barbary Coast. Adam Nichols estimates that between the late 1500s and the early 1700s, the Barbary pirates might have enslaved as many as 25,000 Britons. In 1650, there were more Englishmen enslaved in Africa than there were Africans enslaved in the English colonies that became the United States.

In 1444, enslaved Africans disembarked from Portuguese ships at Lagos in the south of Portugal. Around that time, Portuguese traders began shipping Africans as slave labor to sugar plantations on Cape Verde and Madeira, islands off the coast of West Africa. African kings, chiefs, and slave merchants assisted the Portuguese by selling Africans into slavery in exchange for rum, guns, and other goods. Within a hundred years, people of African descent would become a significant minority group in Portuguese cities such as Lisbon. With bases on the west coast of Africa, Portuguese traders quickly dominated the early transatlantic slave trade and continued to do so for 150 years.

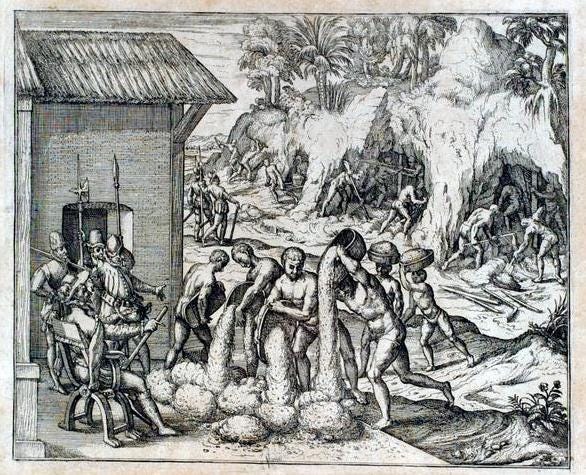

In the 1500s, the Spanish began importing enslaved Africans into the Western Hemisphere. In 1525 a slave ship arrived in Santo Domingo, Hispaniola, with 200 captives. Black sailors, mostly enslaved, some of them free, at times participated in the colonizing efforts of both Spain and Portugal. The conquistador Juan Garrido, a free man of African descent, took part in the Ponce de Leon expedition that explored Florida as well as the Cortes expedition that laid siege to the Aztecs. The first African slaves in what would become the United States arrived in 1526—well before 1619, one might note—at the Spanish colony of San Miguel de Gualdape, near modern-day Savannah, Georgia. There were enslaved Africans in the first permanent European settlement at St. Augustine, Florida. Between 1581 and 1640, an estimated 450,000 enslaved Africans arrived in Spain’s colonies in the Americas; roughly half were brought directly from Africa under the Spanish flag.

By the mid 1600s, racial slavery had been institutionalized in the Catholic colonies controlled by Spain and Portugal. Soon the Dutch, English, and French would become heavily involved in the transatlantic slave trade. The Dutch and English had begun using enslaved Africans on their sugar plantations in the Caribbean, where slaves worked in brutal conditions and typically died after a few years.

Between 1500 and 1866, Portugal, Britain, Spain, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark together transported an estimated 12.5 million Africans involuntarily to North and South America. Roughly 95 percent of those slaves were sold to plantations in the Caribbean and South America. About 450,000 were sold to buyers in North America. Because the birth rate exceeded the death rate, the population of African American slaves in the United States increased to 3.95 million people by the 1860s, when the total population, slave and free, was 31.5 million.

Early in 1776, the English-born writer and revolutionary Thomas Paine urged the American colonies to separate from Britain: “We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” he wrote in Common Sense. “A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now.”

The American Revolution would soon catalyze abolition laws in the northern states of the new republic (VT, 1777; PA, 1780; MA and NH, 1783; CT and RI, 1784; NY, 1799; NJ, 1804) and supply opponents of slavery around the world with powerful new ideological weapons. But the revolution did not begin the world over again: its floodwaters did not wash away the sins of the colonial era. Lasting 89 years in the South after independence was declared, chattel slavery in the United States was less remarkable for its differences from other slave systems than for its striking resemblances.

Justin Suran, a Camp Hill, PA, resident, has taught history at the high school and college levels. His publications include the book chapter, “‘Out Now!’: Antimilitarism and the Politicization of Homosexuality in the Era of Vietnam,” in the volume Gender and Sexuality in 1968: Transformative Politics in the Cultural Imagination, Lessie Jo Frazier and Deborah Cohen, eds., Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, and a column in Lancasteronline titled, “It’s not you—it’s me, Alexa.” His dissertation, Reason's Frontier (University of California, Berkeley, 2003), explored psychiatric science and therapeutic culture in twentieth-century California.

Very good overview! It’s a myth, ie. a lie, created by propagandists to serve a narrow political agenda. The more the facts get out there, the weaker a hold the propaganda will have. Keep it up.

Thanks to everyone who took the time to read and comment on my essay. As a teacher, I always looked for but could never find a concise account of the world history of chattel slavery (as opposed to other forms of slavery) before 1619. I was also interested in the historical relationship between chattel slavery and ethno-racial difference in the centuries before the black/white color line came to define slavery in the US. My conclusion: The British colonies and later the United States were participants in a transcultural system of exploitation and forced labor rooted in the ancient and medieval past and pervasive throughout the Atlantic world by the 1600s. Chattel slavery in the United States was less remarkable for its differences from other slave systems than for its striking resemblances. Thanks again for reading and commenting.