Love

WHERE IS THE LOVE?

“White Dudes for Harris” and the missing tradition of WM-for-BW memoir

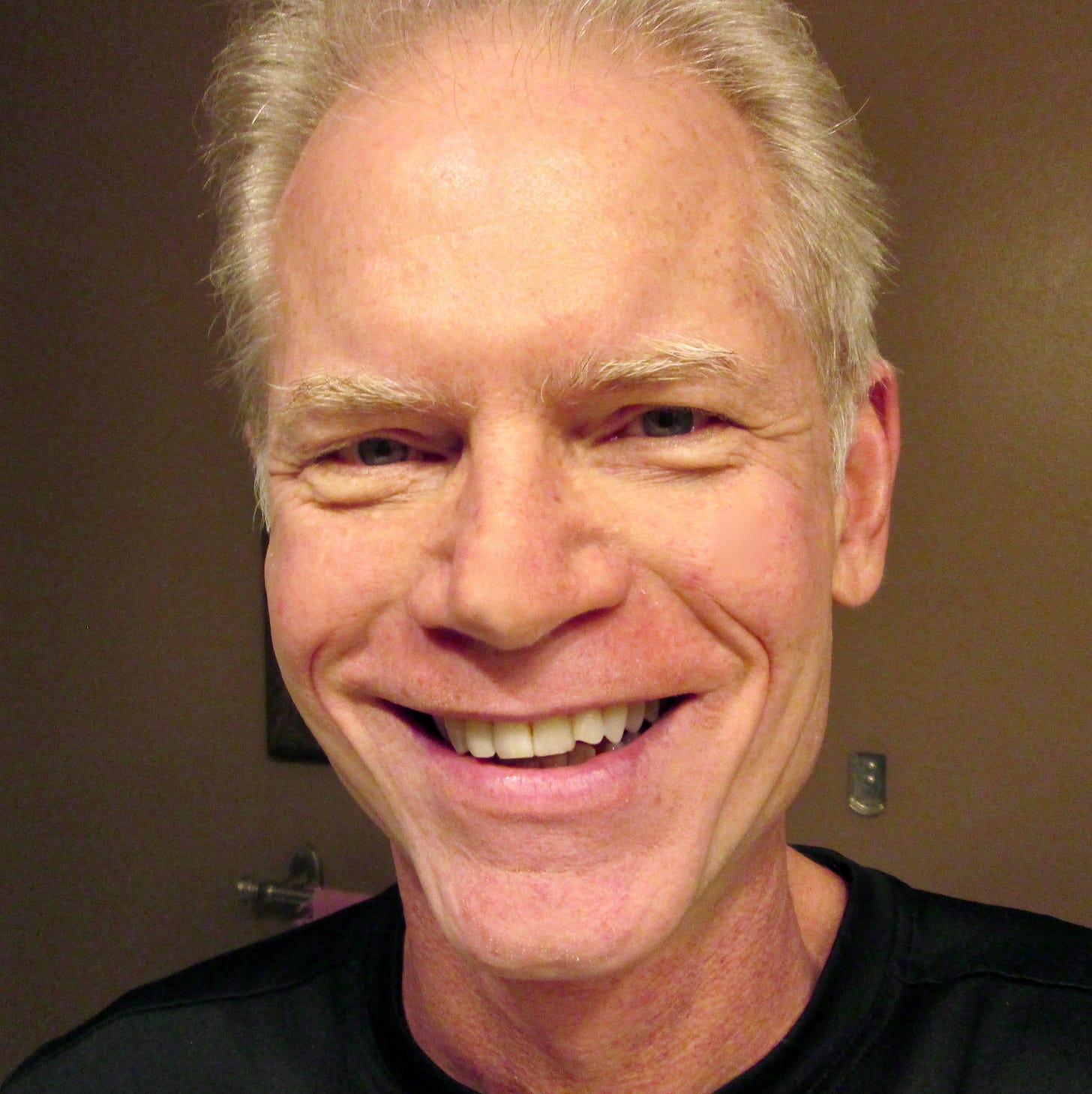

Adam Gussow

One of many things we Americans have lost, thanks to Donald Trump’s stunning recent victory in the US presidential election, is the chance to see an interracial First Couple installed for the first time in the White House. This is especially poignant for those who, like my wife and me, happen to slot into the BW/WM category, homologous with Kamala Harris and Doug Emhoff. Sherrie and I remember well the frosty November night in 2008 when, watching TV with friends while our two-year-old son slept in his Mississippi bedroom, we thrilled as the Obamas—President-Elect Barack, his wife Michelle, and their girls Malia and Sasha—took the stage before a roaring multiracial crowd in Chicago’s Grant Park.

For the first time in history, our son would come of age in an America where a biracial boy could legitimately dream of becoming President of the United States. Couples like us have those dreams—dreams of seeing ourselves and our families reflected at the highest levels of America’s symbolic order. The Kamala-and-Doug dream will have to wait.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that BW/WM configuration ever since the surreal moment in late July, only a week after President Biden withdrew from the field and Harris suddenly, impossibly, became the de facto Democratic candidate, when thousands of self-described “White Dudes for Harris” showed up one night on Zoom to declare their love for Kamala and their willingness to throw money at her feet.

That white-guy-magick fundraiser followed rapidly—and awkwardly—on the heels of two huge and similarly intersectional Zoom events, the first featuring black women and the next, drawing 164,000 participants, titled “White Women: Answer the Call.”

I’m not a fan of identity politics, the self-sorting into intersectional boxes that drove this fundraising trifecta. That deliberate slicing-and-dicing of our democratic polity stands at the furthest remove from Obama’s clarion call, two decades ago at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, to lift ourselves beyond such reductive categories. “There’s not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America,” the unknown young Illinois state senator had famously insisted, “there’s the United States of America.” I agree! E Pluribus Unum!

I’m convinced that Hillary Clinton lost to Trump in 2016 in part because she offered shout-outs to her intersectional constituencies with relentless, autonomic precision—all except white men, of course, whose vote was taken for granted but whose naming was understood to be impolitic. “We all know somebody,” she brayed in her presidential stump speech, “we all know a woman, we all know somebody in a racial or ethnic minority, we all know a worker or a voter, we all know a gay person, and we all know somebody with a disability.” But later, as I brooded on the White Dudes event, cringey as it seemed to me at the time, I changed my mind—not about Clinton’s clunky intersectionalism, but about the importance of white men full-frontally declaring their loving support for a black female politician.

What brought me up short was a surprising discovery I’d made in the arena of literary history. An English professor at the University of Mississippi for the past twenty-two years, I’m about to publish a memoir about my wife, our son, our interracial family and life we’ve made—a surprisingly happy and normal life—in a Mississippi college town. Several years ago, as a prelude to my own offering, I worked up and taught a graduate seminar called “Before and After Loving: Worrying the Color-Line in Southern and Post-Southern Autobiography.”

The reading list included Charles Chesnutt, Thomas Chatterton Williams, W. Ralph Eubanks, Shirlee Taylor Haizlip, Joan Steinau Lester, James McBride, Scott Minerbrook, Bliss Broyard, and Julie Lythcott-Haims, along with the film Loving (2016), which dramatized the marriage of Richard and Mildred Loving and the 1967 Supreme Court case, Loving v. Virginia, that struck down the last remaining anti-miscegenation statutes and legalized interracial marriage across America.

My assigned readings were a representative cross-section of a literary tradition, interracial family memoirs, that hadn’t been extensively studied. But there was a curious lacuna, one I scarcely noticed at the time: none of the memoirs were written by white men.

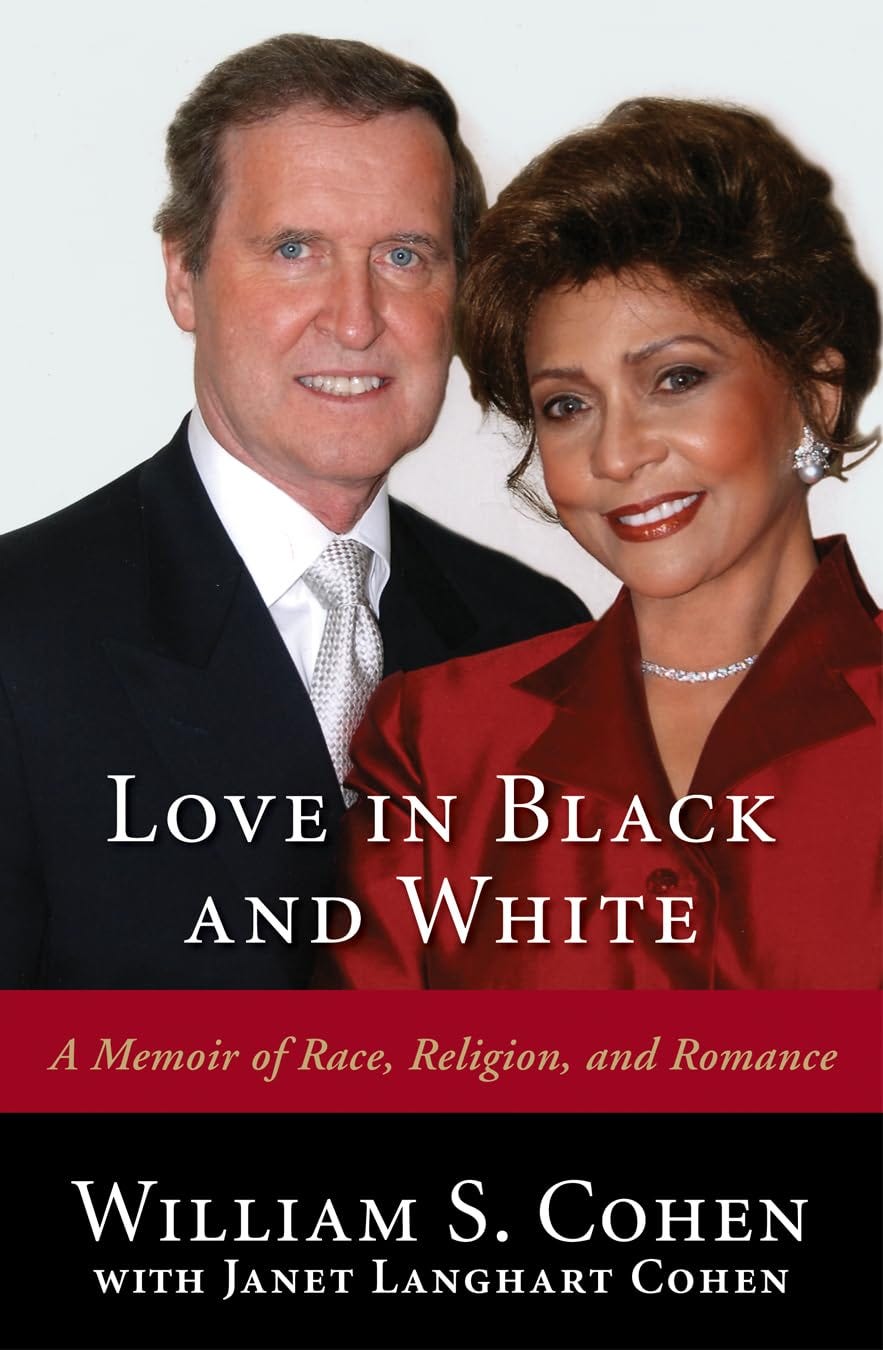

After “White Dudes for Harris” had come and gone, I decided to go looking for what I’d missed. I’d written such a memoir myself; surely there had been others in the five-and-a-half decades since Loving, perhaps even in the long run-up to that watershed. A basic due-diligence search—Google, Amazon books, the catalogues of several large research libraries—quickly unearthed one possible aspirant: Love in Black and White: A Memoir of Race, Religion, and Romance (2007), coauthored by former US Senator and Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen and his wife Janet Langhart Cohen.

Yes, it offered Cohen’s bold public declaration of love for his beautiful, accomplished bride, and hers for him: unusual even at that Third Millennium moment, and prophetic when viewed in light of Obama’s epochal election the following year. But the alternating chapters—now his story of a white man’s Maine youth, now her story of a black woman’s coming of age in Indianapolis and Chicago—made it something less than the self-evident precursor I was seeking, as did the fact that Cohen and Langhart, both of whom were in their mid-fifties when they married, produced and raised no children together. Still, it was a start.

And then, astonishingly, the trail went cold. It dissipated into a handful of not-quites and yes-buts. The TV series “Bob Hearts Abishola” (2019-2024), centered around the unlikely romance between a white Detroiter and a Nigerian-born nurse, unabashedly celebrates WM-for-BW love, but it’s a sitcom, not a memoir.

Prince Harry’s bestselling memoir Spare (2023) shows the transformative, disruptive potential of WM-for-BW romance at the highest level, especially when marriage leads to children, which is to say royal heirs. But Harry is British, even though Meghan hails from California—so we’ve ended up, again, slightly adjacent to the American literary tradition in question.

In Skinfolk: A Memoir (2023), historian Matthew Pratt Guterl brilliantly navigates the minefield that was his own singular interracial family, one consisting of two idealistic white parents, their two white boys, and four accumulated adoptees—two black boys and an Asian boy and girl. Vivid and memorable, driven by an unappeasable pessimism about American race relations, Guterl’s book easily earns a place on my syllabus. But the author himself, married to a black woman and raising his own mixed family, keeps that family almost entirely offscreen. Perhaps he’s got another book to write about them, but Skinfolk isn’t that book.

Finally, as I discovered while making my search, there’s a hugely successful subcategory of chick lit called BW/WM romance: hot-and-sweaty bodice-rippers, all of them—it would seem—authored by black women, not white men. I’m happy to know they’re out there! Google “Tracey Livesay” and you’ll find titles like Have Yourself a Billionaire for Christmas: An Interracial Holiday Novella, Pretending With the Playboy, and, in the “American Royalty” series based on the Harry-Meghan romance, The Dutchess Effect.

Romance novels aren’t memoirs, but they suggest that there’s a real hunger out there among black American women for—well, swirl love. Passionate declarations of undying affection from white men like me.

Surprised that I’d found so little in the matter of WM-for-BW memoirs, I contacted a pair of celebrated senior scholars—a specialist on interracial literature, an historian of the Thomas Jefferson / Sally Hemings affair—and asked them what I was missing. Where, in the pre- and post-Loving world of American letters, were the single-authored memoirs by white men celebrating the love they’d shared, the lives they’d made, and the children they’d raised with the black women to whom they had pledged their troth?

Neither scholar could name a single book. With the passing exceptions I’ve already noted, there was no tradition of interracial family memoirs authored by white men. Mine, not yet published, would apparently be the first.

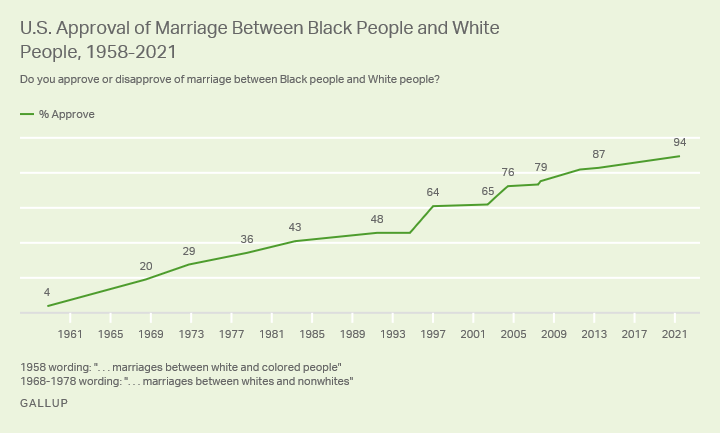

Which is astonishing, when you think about it. The Loving decision was fifty-seven years ago. We know, from the Gallup polls tracking such things, that American attitudes towards interracial marriage have turned inside out over the years, so that 4% approval for black-white intermarriage in 1958 (the year I was born) had been transformed into 94% approval by 2021.

There are plenty of WM/BW marriages like mine out there. So why aren’t the white men in those marriages writing about them? To paraphrase John Donne’s “A Valediction: Forbidden Mourning,” why are so few men like me willing to put pen to paper and tell the laity of their love?

Which brings me back to “White Dudes for Harris.” As I brooded on this question of the seemingly non-existent tradition of WM-for-BW memoirs, I suddenly stopped cringing. Maybe White Dudes for Harris, the full-throated declaration of support for the candidacy of Kamala Harris by thousands of American white guys, wasn’t just a good thing, a distinctly non-cringey thing, but long overdue. Maybe it was more unusual, and more urgently needed, than I had realized: a breakthrough moment in American race relations, perhaps. Maybe it was the very first time in American history that so many white men, as white men, had dared to show that sort of public affection for a black woman. Maybe, just maybe, a lot more declarations of this sort are needed.

The Kamala-and-Doug dream will have to wait. Inaugural Day 2025 will feature a different cast of characters, although the exiting VP and the Second Gentleman will be in attendance. But the field of action is open, the times are a changin’, and that better day will come.

Adam Gussow is a professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi and a professional blues harmonica player. He is the author of numerous books on the blues, including Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition (2002), Beyond the Crossroads: The Devil and the Blues Tradition (2017), and Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music (2020). A longtime member of the blues duo Satan & Adam, he and guitarist Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee were the subjects of a 2018 documentary by that name that screened on Netflix for several years. His new book, My Family and I: A Mississippi Memoir, will be published next February by Emancipation Books. His previous essays for JFBT include “Bilbo Is Dead: An Interracial Family in Contemporary Mississippi” and “The Freest Thing on Earth: A Black Woman, White Men, and the Latest Battle of Ole Miss.”

“There are plenty of WM/BW marriages like mine out there. So why aren’t the white men in those marriages writing about them?”

Because it has become ordinary to people. Most don’t care what other people do as long as it doesn’t affect them. The question suggests that the author is fighting for a cause that’s already been won.

I've been married to my black wife for over 36 years; we have two children and one grandchild. While the only people I encounter who bring up our different races are liberals, I have learned over the years to never discuss race (in the context of our marriage) with anyone.

Our relationship has nothing to do with politics, and never will.