White Privilege

My encounter with a bad idea

Antiracism

WHITE PRIVILEGE

My encounter with a bad idea

Quay Hanna

I was born and raised five miles outside the small town of Strasburg, which is neatly nestled in the southern end of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Both sides of my family had been kicking around in these parts for more than two centuries and being a “southern-ender” (as people in Lancaster refer to those of us from this area) is an important part of my personal story. The Hannas, Hukeys, Witmers, and Trouts (my paternal and maternal grandparents) were all from the southern end and my parents had continued the tradition of raising us in this environment, surrounded by woods, farmland, and pickup trucks. The southern end is an interesting and conflicted area. It’s a stunningly gorgeous countryside, characterized by Amish farms and buggies clip-clopping down the road. But it also has some of the highest rates of poverty and crime outside of the city of Lancaster, which is about 15 miles away.

I grew up in a very stable two-parent home with my brother, sister, and a mom and dad that loved me. My dad was a Vietnam vet and third-shift truck washer for United Parcel Service for thirty years before retiring to focus on taking care of our two-acre property. My mom stayed home until we were all through 6th grade, at which point she took a job as a crossing guard for Strasburg Elementary School. My dad really wanted me to go to college since no Hanna had ever done so. I still remember what he told me: “Son, every morning when I finish my shift at 4:00 am, I’m physically exhausted. Now that I’m older, it’s really starting to catch up with me. You’ve got a good mind; I want you to go to college, so you don’t have to feel like this all the time.” I wasn’t the best college student, but dad taught me to work hard, and I graduated from Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania with a B.A. in English in 1992. In fact, I finished debt free because dad and I paid for all it ourselves along the way. Back in those days you could do it by working a lot of overtime and pinching pennies wherever you could.

It’s this personal background that I remembered the first time I heard about something called “white privilege.” It was the fall of 1997 and I had been getting a lot of local exposure for the work against racism that I was doing at Penn Manor High School in Millersville, Pennsylvania. Shortly after the release of my book Bus America: Revelation of a Redneck, which details the positive transformation of my own racist attitudes, I was asked to participate in working with both the perpetrators and victims of a significant racial incident that had occurred in the district. I did an assembly for the student body and then began meeting with the two primary groups involved in the incident. We eventually put these two groups together to help them air their grievances and also arrive at many points of agreement. We ended the year as a unified club dedicated to truth, patience, understanding, and respect.

After several local newspaper articles about the progress we were making, a middle-aged white man came to visit me at the one-room hut in which I was living at the time and proceeded to explain how my approach to race relations was actually doing more harm than good. He introduced me to the concept of “systemic racism” and emphasized that this was the real heart of the issue. He went so far as to say that my focus on interpersonal conflicts among students of differing skin colors was doing nothing more than perpetuating the true problem of “white supremacy.”

He encouraged me to re-examine my approach and to take into consideration the ways in which the rural white students and I were benefitting from “white privilege.” He told me that until all us white people were willing to renounce this entitlement, our interpersonal efforts at racial healing were like sticking a band-aid on a gushing wound. In fact, by “forcing” the black and brown students to meet with us on our terms, we were actually increasing the chasm of inequity, not bridging it. This conversation caught me off-guard. Most people who spoke with me about my work at Penn Manor agreed with my approach and my goal. The only real criticism I had ever received was from racist people who preferred segregation and hatred.

Since I had never heard of “white privilege,” I asked the man to elaborate. He explained that I had a great many advantages because of my skin color. He highlighted my stable upbringing, pointed out that I hadn’t experienced poverty, and referenced my opportunity to go to college and pay for it as I went. He told me that I had to recognize all these privileges and acknowledge that people like me played a role in creating a system that oppresses black and brown people. In fact, I had to do my part in bringing down that system and building a new one.

Since the man knew very little about me other than what he read in the paper, I informed him that my dad—the son of a mother who died when he was two and an alcoholic father unable to take care of him—had grown up in poverty. He was raised in foster homes for almost a decade before a relative finally took him in to help work on the farm. My dad kept the outfit he was wearing that day—the only set of clothes he had at the time—to remind himself of where he started and his desire to change the path his family would be on. The Hanna side of the family was filled with alcoholism, drug addiction, unemployment, suicide, and even murder. My dad was determined to restore the family name, to discard a legacy of defeat, and create a new family ethos rooted in responsibility, wisdom, and success.

I also shared with the man stories about the many people whom I had encountered in my life. I had met thousands of people in college and on my travels around the world and they came from a wide range of backgrounds, some with stories like my own and others that came from extremely wealthy circumstances and environments. I tried to point out that it seemed to me that no matter their skin color, those who succeeded were the ones like my dad, who worked the hardest and made the most of whatever opportunities they had been dealt. I had rarely met a human being that didn’t have many obstacles to overcome, both from within their family and from the society around them. I told him that I was extremely grateful for the good fortune of my upbringing, but that linking it to my skin color was insulting.

He continued to press me and pointed out that I kept referring to individuals, not groups. He said, “If you look at the overall statistics, you’ll see a large disparity in many areas between black and white people. It’s the system that is corrupt and you’re missing it. The only reason your dad was able to overcome the obstacles he faced was because of his privilege.” In my mind, this took the offense to another level. I responded, “But aren’t systems made up of people? People who are individuals? Don’t you think that building strong, confident, hardworking, tolerant individuals will make a more equitable system no matter what skin color they have?” He responded with something like, “You can only say that because of your white privilege which comes from within this oppressive system.”

I had clearly become agitated and I guess he figured it was time to leave. He encouraged me to read a book he had written about this topic and to honestly consider the truth about racism. He said that if I genuinely wanted to institute change in my community, I needed to confront my privilege and do the work to put an end to it.

As I watched him drive away, I remember thinking, “I’m going to investigate this more, but I’m confident that you’ll never sell white privilege in my subculture. Never.” I believed I could help people think differently about race, but I was certain that “white privilege” would never sell in my community. I’m from a working-class area full of working-class people whose lives had been too difficult to believe that they were the beneficiaries of privilege, especially privilege linked to their skin color. However, since I was still learning about race relations, I wanted to be open to the idea that I was wrong. To be completely honest, though, I felt that even if it were true, ascribing success to some sort of “privilege” would never, ever be accepted by the people in my community.

It’s now 25 years later and I have studied and read tirelessly about racism and race-relations. I have spent a great deal of that time interacting with people from many different backgrounds, many different cultures and subcultures, and of many different skin colors. My career is focused on hearing the stories of teenagers from all different walks of life as they try to figure out how to overcome their own obstacles and tribulations. I frequently find it remarkable how resilient so many of these young people are in the face of extreme difficulties. Some of them remind me of my dad, trying to improve upon the circumstances of their upbringings and change the trajectory of their family history.

I understand what the proponents of “white privilege” are highlighting. They’re trying to say that the continued racial disparities we see in income, housing, crime, and addiction are due to racism that is baked into the system. If there are still disparate outcomes of groups, then the issue must be systemic. If some individuals from marginalized racial groups succeed, it’s only because they have internalized the racism, or become pawns to the system, or have figured out a way to make themselves “white adjacent.” When my white visitor sat across from me and talked about my white privilege, I was convinced it would never be accepted in my community, working class white America. I still think that’s true.

What I still don’t understand 25 years later, however, is who isn’t insulted by the concept of “white privilege,” no matter what color they may be? On the one hand, successful white people—even those who have overcome great odds—are merely beneficiaries of their skin color. They shouldn’t revel in their success for very long knowing this truth. On the other hand, people of color who succeed only do so because they’ve sold out to the corrupt system. The implication is that the only people who are true to themselves are the “losers” who refused to play by the “rules of the system” and paid for their authenticity with failure.

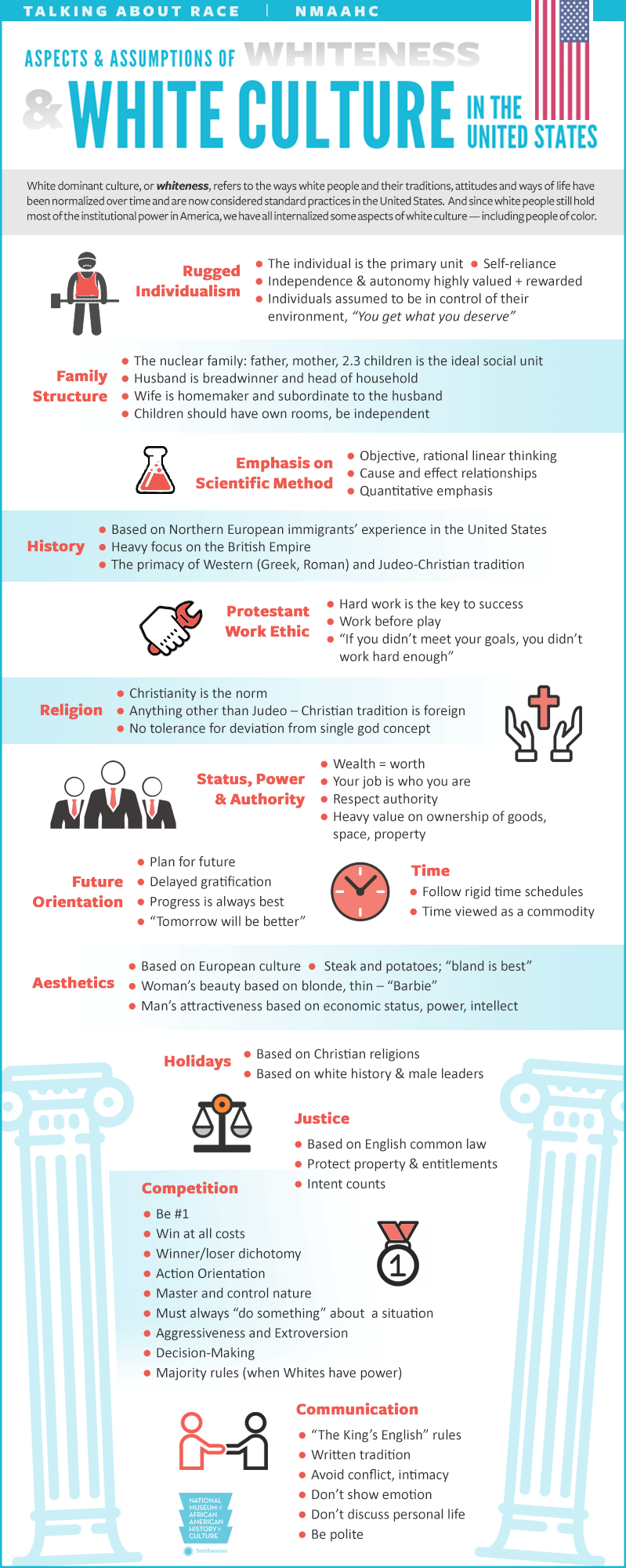

I’m exaggerating to make my point, but there’s a reality to this line of thinking. In 2020, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture launched its infamous infographic (figure 1) that outlined the characteristics of “whiteness” and “white culture.”

“White” traits include: self-reliance, the nuclear family, rational thinking, hard work, respecting authority, delayed gratification, time as a commodity, and being polite. The argument goes something like this: the system has been set up in such a way that those who manifest these “white” character traits will thrive and those who don’t will fail. Apparently, we are to assume that things like hard work, delayed gratification, and being polite are not authentic characteristics of people of color. One wonders how the activists think a culture or society devoid of these characteristics could thrive. Do they imagine a happy society, free of white people and their “white” values, in which everyone relaxes all day, satisfies their every desire instantly, and engages in impolite exchanges? I remember when we used to call this sort of thinking “racism.”

“White privilege” is sometimes described as “not having to think about your skin color” as you navigate daily life. I understand this idea, but I’ve always argued that it depends where you are. I’ve spent time in all 50 states and have crossed the U.S. nine times to see the country. Included in my many life adventures was living in North Hollywood, in Los Angeles, in my mid-twenties. When I moved there, I immediately stood out because of my lighter skin color, my Pennsylvania accent, and the fact that I spoke English, not Spanish. As a white guy from Strasburg, I was initially well aware of my skin color.

What I eventually found, however, is that most everyone in North Hollywood was just a fellow human being, and working class at that, just like me. Once they realized I was now part of their community, they accepted and welcomed me. My relationship with this community was rooted in hard work, self-reliance, and respecting authority, among many of the other “white” characteristics we read about. Was it my “white privilege” to be able to utilize my “whiteness” to intimidate and subjugate my Hispanic neighbors? Or was this a case of “white adjacency” on the part of the Mexican / Mexican American population that dominated that part of the city? Or was this, instead, a case of people of differing backgrounds successfully living together in a way that allowed for true freedom and thriving?

I think it’s good for people to recognize and be grateful for the privilege of living in America. I also think it’s important to examine history to see how privilege has played a role in our society. But it’s hard for me to buy that I am “privileged” because of my skin color when it’s being sold to me by people with ivy league degrees, who sell millions of books, appear constantly in print and on television, and make seven figures a year. I knew you couldn’t sell white privilege in my community 25 years ago, and I’m certain you still can’t.

Maybe it’s time to retire the concept of “white privilege” and focus instead on what universal traits really allow for the freedom to pursue life, liberty, and happiness. That way, we could try and find places of commonality and an agreed upon set of standards by which we can live in community and thrive. Then we can all celebrate our “human privilege” in making it happen.

Quay Hanna is the author of Bus America: Revelation of a Redneck, which chronicles his 1993 journey around the U.S. by Greyhound Bus and the transformation of his previously held racist and prejudicial views to respect for and understanding of his fellow human beings. He has done more than 1,400 presentations over the last 25 years in schools around the country. Additionally, he works as a youth mentor in multiple school districts struggling with race and student relations. Quay has been awarded the Human Relations Award from the National Conference of Community and Justice and the Child Abuse Prevention Award from the YWCA. In 2006, he was one of 300 people invited to the White House Summit on School Violence. He is currently a Fellow at the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR). You can find out more via his website or follow him on Instagram or Twitter.

" “White privilege” is sometimes described as “not having to think about your skin colour” as you navigate daily life. I understand this idea, but I’ve always argued that it depends where you are."

This is a really interesting point. I live in the countryside of the UK as an African and I was always aware of how I looked when I was out and about. And noticed I didn't think about my skin when I was around people who looked like "me". I couldn't articulate this feeling until I read somewhere that it was because of white supremacy since white people don't experience that. Which now as an adult I realise is completely stupid. I live in England, home of the English. And the dominant culture is theirs. The same way I don't think about my physical differences when surrounded by my ethnicity, they don't think about theirs surrounded by their ethnicity. The same is true for every country and the dominating ethnicity. The answer to why I felt this way was so simple, looking back at it, that it's borderline funny.

It's just part of being human, noticing obvious surface level (emphasis here) differences. To be completely candid, I used to get stuck on these differences and turned a collective of individuals into a caricature. Yet when I saw people who looked like me. African or Muslim etc. I saw them as human, nothing more attached to that. It wasn't until I heard about how people outside of this "group" saw us, that I was completely floored and reflected on the stereotypes I held about others.

I remember a "white" American joking with me that his son (who I'm friends with) should be careful because if he sees my hair, he'll have to marry me! I found it hilarious because I've never heard that before and didn't know people thought that. I had a similar reaction when an English man on a train told me to stop listening to the patriarch of my family, not knowing I was the eldest daughter of a bereaved widow. There was no patriarch. It's just funny to be in these (isolated and infrequent) situations because it takes me outside of myself.

Just a really good point you made, combatting that baseless claim and emphasising looking at the individual. Which is one of the best ways to dissipate any subconscious biases one has unknowingly placed on a "group". And when you do meet someone vastly physically, culturally different to you, see them as one person from x y z background. Not that background itself. And when I do meet someone that is racist, who is racialised as white, I try and combat my knee jerk reaction and imagine the roles reversed (I know, hated term). But imagining them as a racist from my ethnicity helps me see them more clearly. Weird, no real threat and more importantly a human who's behaving "badly". Not a bad person.

If I receive the full benefits of the law and have my civil rights respected how is that "privilege"? If people respect me in public and treat me fairly how is that "privilege"? If the police don't mistreat me how is that "privilege"?

Aren't all these things just the baseline standard of civilization? Aren't all these things simply the way liberal democracy should operate instead of an invisible form of apartheid? Shouldn't the issue be that certain people or groups are not receiving these benefits of civilization and how to rectify that?

This reminds me of a story I read about the Soviet Union:

"It’s 1917, and an old lady hears a commotion in the street.

“What is happening?” she asks her maid.

“Oh, it’s so exciting! They are protesting in the street!”

“What do they want?” the old lady asks.

“They want for there to be no more rich people!” says the maid excitedly.

The old lady sighs. “In my day they protested too, but back then they wanted for there to be no more poor people.”

This is always where Leftism ends up: pointing out some form of inequality or oppression, first trying to lift those on a lower level upwards, realizing how difficult that is, then quickly moving on to what really gets the blood flowing: attacking those who exist at the top of their imaginary pyramid of Oppression (whether that be the bourgeoisie, the kulak, and now White people), hoping to level them downwards as a way to bring about the egalitarian Promised Land.

In all its previous incarnations, Leftist rule or Leftist uprisings have only caused social destruction and a vast expansion of group hatred.

It is the same this time.