Religion

ZIONISM AND THE BLACK CHURCH

My Journey of Spiritual Legacy

Dumisani Washington

I have written a book, titled Zionism and the Black Church, arguing that there is one universal Church. It holds that the Body of Christ is not Black or White. It is one Body. The book is not an effort to divide Christians by race or ethnicity. The term “Black Church” in the title does not refer exclusively to a specific group of Christians, be they Baptist, Church of God in Christ, African Methodist Episcopal (AME), Hebrew Roots, or Messianic any other denomination. From the birth of the Church at Pentecost in first-century Jerusalem, there have been multiethnic congregations. The book addresses Christian Zionism, which is a discussion that is paramount for all Christians regardless of ethnicity and for our Jewish brothers and sisters who may want to know more.

In Zionism and the Black Church, I speak to the cause of Israel and the Jewish people, a community purposefully targeted with an antisemitic, anti-Zionist message. Once the lowest caste of any people in the Western world, reduced to chattel slavery, Black Americans generally have a sought-after perspective on issues of humanity. This is especially true of the Black Church. The legendary Black struggle for justice has historically given the Black Church an air of validity and authority. Though a small portion of the U.S. population, Black people have influenced everything from music and art to theology, politics, education, and, of course, civil rights.

I started the Institute for Black Solidarity with Israel (IBSI) in July 2013, responding to what I can only explain as a divine call. I also served as the Diversity Outreach Coordinator for the now over ten million member Christians United for Israel (CUFI) from September 2014 to May 2021.

My son, Joshua, currently serves as IBSI's Director. By profession, I am a musician, a piano performance graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. I am a pastor, a husband of 34 years to an extraordinary woman and a father of six extraordinary children. I am also a Christian Zionist, meaning I believe the Jews are God's chosen people, and the land of Israel belongs to them. I also believe, however, that Israel's right to live in peace goes well beyond scriptural interpretation.

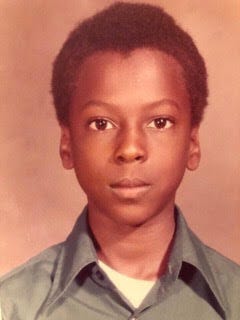

I was born Dennis Ray Washington on February 17, 1967, in Little Rock, Arkansas, the segregated South. I am the youngest of seven children. We moved to California when I was about one, so I have no early memories of Arkansas. I legally changed my first name to Dumisani in the early 1990s to embrace my African heritage. Dumisani means praise from the Zulu phrase dumisani u Yehovah (praise the Lord). My dear friend and sister Nomathemba Sithole, a South African national of the Zulu tribe, helped me choose my new name. Nomathemba is affectionately known to our family as Malume, “Aunty.”

My parents, David and Lillian Washington, were both from the Little Rock area. They were born in the early 1940s and were part of a vibrant Black community. My mother was a seamstress from a young age. My father’s father was a sharecropper, so my father grew up on a farm that grew all sorts of crops, including cotton. My father did not graduate from high school in large part because he had to run the entire farm by himself when both his brother and father fell ill.

My mother often spoke about Little Rock and the life of the community she loved. We were active members of King Solomon Baptist Church, where Reverend Thomas was the pastor. My mother told me that I loved music so much as a baby that I would rock and sway as the choir sang. Unfortunately for Reverend Thomas, I was not fond of preaching. I would cry at the top of my lungs whenever he took the podium. My mother had to take me out of the sanctuary virtually every week after the music ended. Perhaps I just wanted the music to continue. Either way, Mama said I gave our pastor a complex. She was not joking.

My father was a gifted singer, a leader of the men’s chorus, and served on the deacon board. My mother was a deaconess and worked with the youth ministry, among many other things. She graduated from the only high school for Black children in Arkansas, Scipio Africanus Jones High School in Little Rock. S. A. Jones High School was the pride of Arkansas. Like many Black schools during segregation, there was a deep sense of connectedness among the teachers, administrators, and students.

Throughout the history of Black people in America, education was the primary means of freedom and upward mobility. Black students from S. A. Jones graduated and went on to become doctors, lawyers, politicians, athletes, clergy. My uncle, Dr. Levi Adams class of ’51, had a long and illustrious career with the medical school administration at Brown University in Rhode Island. At Brown, there are two awards that bear my uncle’s name: an undergraduate award for service in a religious organization, project, or initiative and a scholarship for African American medical students at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School.

Though I never directly experienced it, hearing my parents describe life in North Little Rock gave me a great sense of pride. I learned of the Little Rock Nine—nine African Americans who enrolled and participated in the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock in 1957—from my parents, who knew the families involved. I learned of the internal debate over integration. Many Black people knew that it would mean the end of their beloved S. A. Jones and other Black institutions in Little Rock. S. A. Jones closed in 1970 because of integration. The teachers and administrators were released and not allowed to work in the now “integrated” schools. For this reason and many others, my mother explained to me at a very young age; she was vehemently against forced integration.

My parents did not teach us hatred and contempt for White people. They taught us what racism was so that we would be prepared to face it. They taught us not to ascribe virtue or wickedness to someone simply based on their ethnicity. One’s character was who one was, not one’s race. They also taught us to speak our minds and not be afraid of anyone’s disapproval, a lesson they demonstrated as much as they articulated. One of the most vivid stories my father told me was when he was about ten years old. The White landowner had come to the farm to check on my grandfather’s work. As my father and grandfather were busy in the field, the landowner pulled up in his pickup truck and began berating my grandfather. My grandfather stood silently, avoiding eye contact as the man disrespected him in front of his young son. After a few moments, my father had all he could take. He abruptly climbed up the driver’s side door of the pickup, got directly in the White man’s face, and said, “Hey, mister! I don’t like the way you talkin’ to my daddy!” At ten years old, my father did not fully understand that what he had just done could have gotten both him and his father killed. My grandfather gently removed my father from the man’s truck, saying, “Junior, get down.”

No more than ten myself when I first heard the story, I asked, “What did the man do, Daddy?”

“Nothing,” my father replied. “He was stunned. He just looked at my father, then looked at me, then looked back at my father, and drove away.”

I read the Bible as a child and was intrigued by all things Israelite. Though I loved reading the gospels and “walking with Jesus” through the scriptures, I was even more drawn to the Old Testament. I knew the stories of David and Goliath, the Patriarchs, and the Exodus by heart. As a young adult, I wanted to learn more about the Hebrew roots of my faith and met Jewish musicians who introduced me to the feasts (Passover, Tabernacles, etc.). They shared songs and prayers in Hebrew that began to transform my worship and my songwriting. In the mid- 1990s, I began researching the Jewish Diaspora, as I was captivated by news of Beta Israel, the Jews of Ethiopia. I began to follow current events regarding Israel and Africa and learned about the absorption process of the Ethiopian Jews. All of these seemingly disparate strands of my life would become woven together years later.

A friend and fellow musician had a band that performed a unique style of the Songs of Zion and music of the Jewish people. I joined the band for a series of CUFI events called A Night to Honor Israel. At these events, I began learning more about modern Israel, the people, the culture, its global charitable work, its breakthroughs in innovation and technology, and Israel’s defense and military concerns. I also began to learn of the Palestinian refugee crisis and the nature of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Black American history was something I first learned in my home as a child at the dining room table, in my mother’s sewing room, and kitchen. As a young adult, I learned of the South African fight against apartheid from Malume, who had lived it. Knowing the atrocities of apartheid laid bare the false claims of Israeli apartheid. When I understood how the historic Black struggle for justice was used by Israel’s enemies to demonize her, I was personally offended. I learned of notable Black Americans in the 1970s who were also offended at the false claim that Zionism amounts to racism and voiced their eloquent opposition. Knowing I was not alone gave me great comfort.

The first time I spoke publicly on the subject of Israel was at a Sacramento City Council meeting in 2012. The leaders were considering a measure to become a sister city with Ashkelon, Israel, and there was an open hearing. In a packed room divided along ideological lines, I experienced my first virulently hostile, anti-Israel crowd. I heard the false accusations of Israeli apartheid, Jim Crow racism and segregation, the genocide of the Arab Palestinians—the attacks were relentless and baseless. When it was my turn to take the podium, I refuted the claims of Israel’s racism and discrimination. I explained that while no nation is perfect, Israel was nothing like what my parents experienced in Little Rock, or Malume experienced in Durban. Israel is a free, pluralistic society forced to defend herself against an untold number of enemies bent on her annihilation. Comparing the Jewish State to what my family endured was beyond egregious, and I let everyone in the chamber know I was there to defend both Israel and the distinctiveness of the African American historical experience. I quickly learned that people who oppose Israel did not respond well to Black people defending Israel. It was shocking to hear the racist comments directed at me by people who were there to “combat” racism. The combination of shamelessly abusing my people’s heritage and lying about Israel, one of the most significant regional partners to many African nations, lit a fire in me that has not diminished.

In the many Israel events at which I’ve spoken since 2012, I’ve heard outlandish terms such as “a sort of apartheid,” “a type of Jim Crow,” and even “a symbolic genocide.” There is no sort of apartheid. There is no type of Jim Crow. And genocide is real killing, not symbolic. I also quickly learned that when it came to slandering the Jewish State, no people’s history or legacy was off-limits. Anyone’s story, no matter how sacred or painful, would be exploited to attack the Jews and their homeland. There is an extraordinary amount of disinformation and anti-Israel propaganda out there.

In any event, my advocacy for Israel had officially begun. After my first trip to Israel during Hanukkah of 2012, I returned and started the Institute for Black Solidarity with Israel (IBSI). During my first speaking tour, on which I met diverse anti-Zionists, I would often reflect on the words of my friend, Yaffa Tegegne. Yaffa is an Ethiopian Jew and daughter of the late Baruch Tegegne, a pioneer in the movement that saw the Jews of Ethiopia finally return to Israel. As a Black Jew and vocal Zionist during her college years in Canada, Yaffa encountered antagonists who simply could not understand her. In a 2013 interview with IBSI, Yaffa recounted:

I studied politics at Concordia University [which had] probably one of the biggest Arab student populations in North America. In 2002-2003 [Israeli Prime Minister] Netanyahu was supposed to come and there was a riot, and we had a huge solidarity for Palestinian rights movement, and there were terrible incidents. I used to literally argue on campus all the time, and I think I was the only Ethiopian Jew and the only Ethiopian they had ever met, and it was very difficult for them. They didn’t know how to deal with it, because it went fundamentally against their entire notion. Like, “Here’s a contemporary story of why we still need Israel. It’s not just the Holocaust. This [Jewish persecution] has been continuously happening in recent times.” So they would have a really hard time dealing with me because I didn’t fit the mold of what their argument was.

My experience in Sacramento in 2012 was similar to what Yaffa described. For many anti- Zionists, a Black person standing with Israel is offensive. They are unaware of or don’t care about the long tradition of Black-Jewish cooperation in this nation. Since it has not been as visible over the past fifty years, I could not say I blamed them. During the lull in Black vocal support for Israel and the Jewish people, many falsehoods and deceptions have been promoted. It has become quite common to meet Black people, especially on college campuses, who have a negative view of Israel, if not Jews in general. As Jamie Kirchick noted in his 2018 Commentary article, “The Rise of Black Anti-Semitism”:

Attitudinal surveys conducted by the ADL [i.e., Anti-Defamation League] consistently show that African Americans harbor “anti-Semitic proclivities” at a rate significantly higher than the general population (23 percent and 14 percent respectively in 2016).

Much of this is the effect of anti-Israel miseducation directed towards the Black community. In 1992, the same ADL survey found antisemitism in the Black community as high as 37%. The good news is that between 1992 and 2016, the antisemitism did decline. But it is still too high.

In the 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. understood well the factors that were adversely affecting the Black-Jewish relationship and the antisemitic feeling fomenting in some circles. He offered a partial explanation in a chapter titled, “Where Are We Going?,” in his 1967 book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?:

Negroes nurture a persistent myth that the Jews of America attained social mobility and status solely because they had money. It is unwise to ignore the error for many reasons. In a negative sense it encourages anti-Semitism and overestimates money as a value. In a positive sense the full truth reveals a useful lesson. Jews progressed because they possessed a tradition of education combined with social and political action.

Some of Dr. King’s most impassioned pleas for continued Black-Jewish cooperation came towards the end of his life. This was also when Israel’s enemies were attempting to drive a wedge between Blacks and Jews and between Israel and the African nations.

Mark Twain once said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” I believe we live in a time similar to the transitional period of the late 1960s and 1970s. Christians are called to stand with and be a blessing to Israel and the Jewish people. Black Americans have a long history of shared struggle with the Jewish people. The issue of Black civil rights took center stage once again with the 2020 killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others. Israel’s enemies are using those tragedies and other challenges within the Black community to manipulate people into blaming and hating Israel and the Jews. Given the power of social media and the now systemic way in which Israel and Jews are characterized on many college campuses, it can be argued that the exploitation is worse now than it was in the 1960s. I explain the deeper purpose of this exploitation of the Black community in an article entitled What the pro-Israel Community Got (and still gets) Very Wrong About Black Lives Matter. Black Christians will be pivotal in this renewed fight for the direction of our community, the Church in general, and our country.

I am humbled to do the work of strengthening the Black-Jewish, Africa-Israel alliance. Not only that, I am extremely optimistic about the future. As Dr. King said, “We’ve got some difficult days ahead,” but we will reach the Promised Land. To my fellows in the church, I say that we will see God move on behalf of those who stand with His firstborn—the Jewish people.

This essay has introduced me and my book, Zionism and the Black Church. I hope it will inspire you to read my book. I pray that if you do read my book, you will be receptive to its message of Zionism and solidarity with Israel. I also pray that any fellow pastors and ministry leaders who read it will exhort their people to walk in the blessing and not the curse.

And I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse, and all the families of the earth shall be blessed in you.

(The Complete Jewish Bible with Rashi Commentary, Genesis 12.3)

Dumisani Washington is the Founder and CEO of the Institute for Black Solidarity with Israel (IBSI) and the former Diversity Outreach Coordinator for the over 10 million member Christians United for Israel (CUFI). He is a pastor, graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and professional musician, and author. His latest book is Zionism and the Black Church: Why Standing with Israel Will be a Defining Issue for Christians of Color in the 21st Century (now in its second edition). He and his wife, Valerie, have been married nearly 34 years and have six children and two (soon to be three) grandchildren.

Follow Dumisani on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, The Hebrew Project, and Twitter.

Great article, thank you. Too many people blindly follow whatever they hear from Amnesty International and the UN, which they take to be the gospel truth.

From the Telegraph: "Israel is a close ally of the West, it has a vibrant and innovative economy, and all Israeli citizens enjoy equal rights under the law. At present, an Israeli Arab party is even part of the country’s coalition government. To Israel’s critics, however, this counts for nothing. The hard-Left seems to be obsessed with Israel, behaviour that borders on anti-Semitic. NGOs such as Amnesty International devote questionable amounts of attention to the country, some say to the detriment of their work on egregious human rights abusers such as Russia and China."

Great read - thank you!