Music / Interview

KNOWLEDGE, ART, AND THE MUSICAL WORLD OF ELIO VILLAFRANCA

Ildi Tillmann

How can we really get to know each other?

By abolishing the frontiers.

Andrei Tarkovsky

Dedication: This piece is dedicated to a little boy born in a Cuban village, to the Caribbean, to Cuba, to Haiti, to jazz in Eastern Europe, to human mythologies, to the orishas, the santos, the lwa of Haiti, and to the power of art to bring us all together.

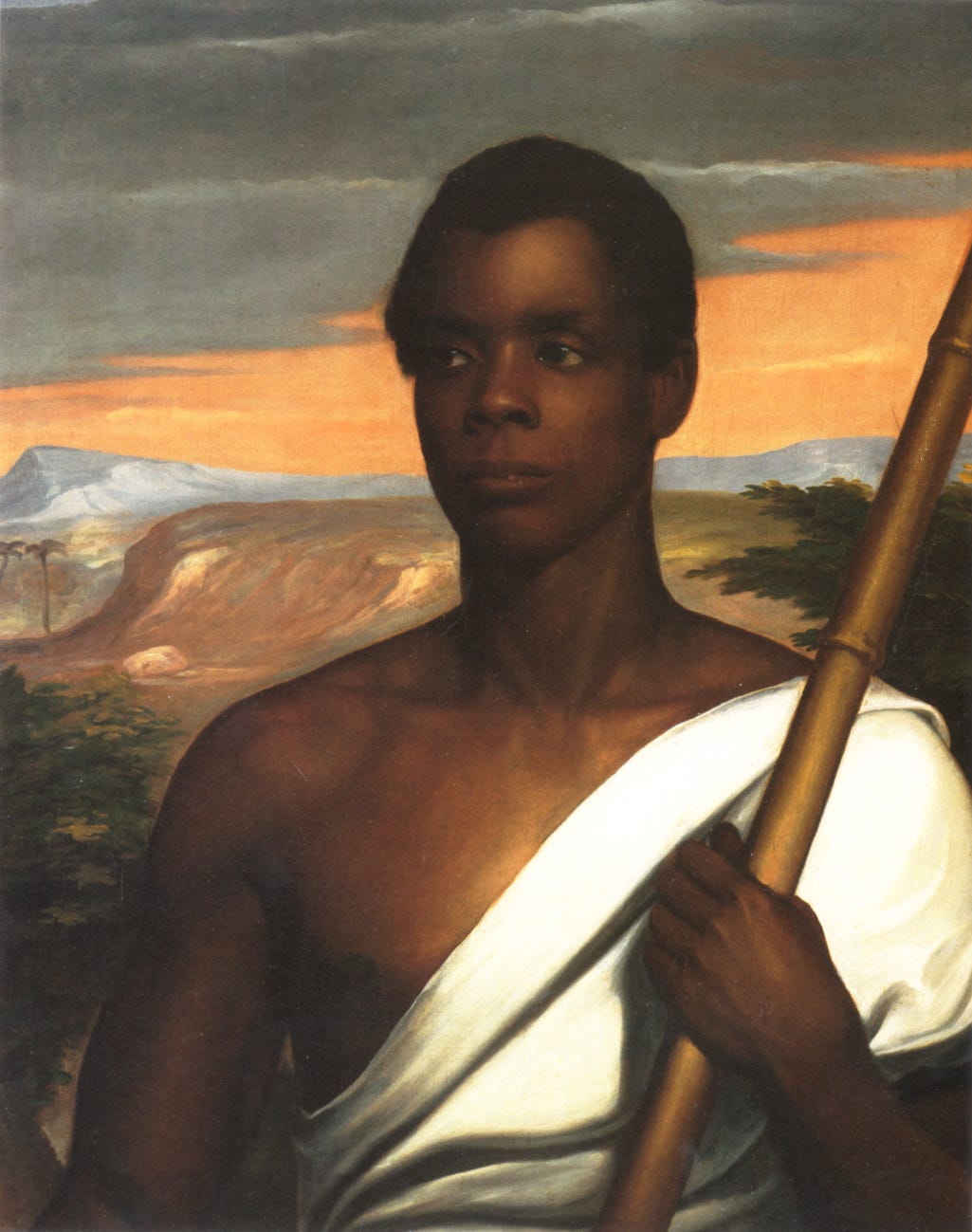

I first heard the Cuban pianist and composer Elio Villafranca play live in the fall of 2019, at Smoke, a jazz and supper club in New York City. He was performing with his band, the Jass Syncopators, presenting music from Cinque, an ambitious double album named for Joseph Cinque, an African who in 1839 led a successful revolt aboard the slave ship La Amistad, days after being sold and transported to a sugar plantation in Cuba. The album—which unfolds over a five movement suite—merges Villafranca’s own compositions with traditional songs and music, taking listeners on a musical journey through five cultures in the Caribbean: Puerto Rican, Jamaican, Cuban, Haitian and Dominican.

Since that fall evening at Smoke, I have listened to Elio Villafranca play many times; his musical talent and his technical virtuosity are without parallel. Equally without parallel is his ability to express, through music, mysteries rooted deep inside the human soul. To be organic and universal, to erase all lines of fracture. To tell stories that are rooted in human experience, but that cannot be recounted in so many words. To create art detached from politics, unconcerned with trends, celebrity, or fashion.

Villafranca writes poetry through sound, melody, and rhythm, thereby bringing us art, period. Creative human knowledge from beyond the confines of the United States. From south of the Southern border.

What follows falls into four parts: first, my reflections on the now-dominant America-centric “DEI” perspective; second, a meditation on the “colorblind” approach to emancipation characteristic of much Latin American thought and action; third, an introduction to my interview with Elio Villafranca; and, finally, the main course, Elio’s story.

1. The past, the present, and our production of knowledge

Higher education in North America has, for decades, been engaged in a project that asserts, as its goal, to widen of the field of acceptable or sanctioned forms of knowledge; to diversify and include in order to arrive at a deeper and more variously sourced accounts of the world. This project seeks to “decolonize” knowledge. Power and political interests have been seen to distort narratives of the past in the Americas and to create blind spots in what it is that the public knows.

This movement has ramified well beyond scholarship and a few academic disciplines into a diversity movement, supported by a sprawling DEI bureaucracy. This bureaucracy promotes its own simplistic worldviews and misguided policies, and often appears to seek simply to reverse traditional hierarchies. Rather than levelling the playing field, it creates new bastions of power. While claiming to dismantle hierarchies and to “include,” this approach has created a proliferating market for new markers that draw ideological lines around groups of people, with hierarchies and assumed fault lines between them.

The movement has given shape to an imagined, ahistorical, and homogeneous version of Europe, which can stand as the new Other (see also “White” and “Whiteness,” as political categories, or markers of singular cultural affinities). Europe-centered versions of history, knowledge, and art, which had truly been limiting and exclusive in the past, are being replaced with a contemporary North American-centered vision of the world that is governed by essentialist notions of gender, ethnicity, and race, that is, by “colonial” thinking patterns.[1]

Rather than fostering diversity and cultural openness, this movement has simply posited a new center, a North American Metropole, which, through its economic and concomitant cultural power, overshadows the perspectives and accumulated experiences of people from other parts of the world—such as the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, Africa, or Asia. It has created a marketing-obsessed, self-referential, and thus inevitably self-centered world, where slogans and simplistic arguments drown out the voices and concerns of people who want to highlight the shared realities of humanity.

We need a decolonized analysis of the DEI powers-that-be of our present. As someone who grew up outside the narrative paradigms of the Atlantic region but who has been living as an American citizen for over twenty years now, I think that it is useful to reflect on the following questions:

Who, in the contemporary Atlantic world, are the truly voiceless, or rather, the unheard or misheard? What version of history is being constructed and told about the world, the Americas, and the people living there right now? Who, in our present moment, wields power, and in what way? Beyond demanding justice and inclusive knowledge, who, if anyone, has created art and knowledge, diverse, transformative, and cross-cultural in form and concept? Do the voices of people who have done that get a proper hearing?

Enter Haiti, Cuba, and Elio Villafranca.

2. Haiti and Cuba: Race, social justice, oppression, and freedom

Historians of Haitian descent have repeatedly pointed out the misleading nature of seeing the social and historical realities of Latin America and the Caribbean mainly through a racial lens, at the expense of class and other factors that influence social relations and power. Political violence, endemic corruption and militarism, are all present in the South American region in ways that detach from questions of race. South of the United States, liberation movements or social justice initiatives have more often than not adopted a non-race-based vision and practice (a “colorblind approach,” to use the North-American jargon).

Such was the fight against the Duvalier dictatorship in Haiti, led by Jean-Bertrand Aristide, with a decidedly universalist political vision and rhetoric, reflecting the wider Latin American liberation theology movement that Aristide belonged to. Such was the leadership role of Antonio Maceo, the Cuban general of mulatto descent, who became the second in command of the Cuban army during the fight for Cuban independence in the late nineteenth century. Such was the resistance against the regime of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, who himself was of Spanish, African, Chinese and likely also of Taino descent, in the mid-twentieth century.

None of this means that racism or colorism have not played a role in the region’s politics or history, but it means that, to challenge oppression in its varied forms, political and cultural thought leaders in South America and the Caribbean tended to prefer a view of the world which considers the individual as the singular unit, and the human race or the nation, rather than racial groups imagined to be static and homogeneous, as the larger community.

3. Music and art: An inclusive approach

Watching Elio Villafranca play Cinque brought these thoughts to the forefront of my mind. A dark-skinned pianist, born in a small Cuban village, granted an education (and therefore an opportunity) by a Soviet-style communist dictatorship, playing music that drew on traditions spanning from classical, through Caribbean to African, embedded in the language of jazz, playing in New York City—this is the embodiment of decolonized and inclusive knowledge and art, in action. It is so not because the composer counts as a ’Person of Color’ as the current category goes, but because his approach to creative expression is free from the limitations of scripted identity and of attendant cultural expectations—free from any framework that privileges a racialized, colonial attitude toward the world. While the music of Cinque, the album, weaves around a story of slave-revolt and freedom set during the Atlantic slave trade, what makes the album inclusive and remarkable in its diversity is not only this story but also the range of traditions it builds on and the composer’s genuine creative freedom to seamlessly fuse them, to defy music-industry categories, and to merge music, song, narration, and anthropological research in the same album, and thereby to create a composite world. This is a bold and open-minded approach, the creative product of which should be part of every inclusive curriculum because it shows how a genuinely talented person, socialized outside of the North American imaginary, thinks about progressive art and culture.

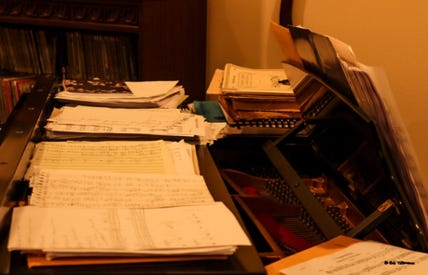

To foreground inclusive alternatives and to cross boundaries rather than redraw them, I asked Elio for an interview that would focus on his approach to music, art, and education. My goal was to create an interview-essay that connects cultures, expressive forms, and disciplines: a piece that informs without academic jargon, has links to music, and incorporates images. A co-created piece between a non-musical photographer of Hungarian origin, and a Cuban composer and pianist whose music makes stories come alive—two individuals from distinct locations, with seemingly different histories, but with many overlapping values, cultural insights, and political experiences.

Elio agreed. I prepared my list of questions and I had him review them before we met. When we sat down to talk, I soon realized that I could put my list aside, as he was already leading the way. He took my first question, as if it were a tune, and ran with it. While keeping to the basic theme of my questions—his personal story in light of musical traditions—he told me the tale on his own terms, from the inside out, passing between times and events. While not sitting at the piano, he was still playing jazz. His story, edited for length, follows.

I was born in a tobacco area in Cuba, in a town called San Luis, in Pinar del Rio. Our house was in the center of town, right behind the courtyard of the Casa de la Cultura [House of Culture, a community center], so I had access to all sorts of musical activities that were happening there at the time. When I was in elementary school, I enrolled in after school art programs at the Casa de la Cultura. First, I did painting for a year, then I switched to playing the guitar. Our teacher at the center was a graduate of the Music Conservatory in Havana, and he taught classical guitar pieces. I fell in love with those pieces, and I decided that I wanted to go to music school to learn to play the guitar well. So that was my first serious introduction to music.

The other type of music I encountered in San Luis was the one played by the workers at the tobacco farms. They were not musicians by profession or by official training, but they played a lot of music, on a type of drum called the tambor yuka, which is a drum of Congolese origin. That music was played on the streets and also in the backyard of the Casa de la Cultura as part of the cultural programs, but it was not taught in any classes. When the farm workers played music in the yard, or prepared the drums from the avocado tree trunks, I loved to peek over the fence and watch them work… I loved watching the flames and hearing the rhythms.

African drumming has a religious aspect to it, yes, but the tambor yuka is not actually a religious instrument, it is a drum that was used for communal gatherings, you would say parties today. The dance that goes with that drum became the basis for the rumba, later on. The tambor yuka is also believed to be the first drum played on the island [of Cuba], because the Native American people of the Caribbean islands did not use drums, at least not according the recorded or inherited traditions that we know about.

Going back to my formal education: when I was 11 or 12 years old, I enrolled in the [regional] music school for children, which was in Pinar del Rio. I wanted to play the guitar, but they had no more available spaces for guitar students, so I settled on percussion, which I had imagined to be like the drums I knew from San Luis. But the music education in the school was strictly classical, so their percussion program had nothing to do with the drums I had known before. I was disappointed. Those were tough years, especially in the beginning, living in a boarding school, far away from my family. It took me a while to get used to that.

This school was the place where I started playing the piano, it was part of the music program for every student. I liked the piano and got more and more involved with it, but it became my instrument of choice only later on.

I went to high school in Havana, to the Escuela Nacional de Arte, which is a specialized school for music, visual arts, drama and dance. During those years I was playing piano (keyboard) for a rock band, and I stayed with them for eight years. We toured a lot, in Cuba and in the Caribbean. But up until my university years I had not encountered jazz at all. My main exposure to music was classical and rock and roll, with the informal Congolese influence from my town.

After high school I applied to the Instituto Superior de Arte [the institute of highest education for music in Cuba, a competitive university with a large campus in Havana]. I was worried that I would not be accepted as a percussionist, so I decided to also apply as a composer, hoping to be accepted at least for one of the two specializations. I was accepted to both, as I won first place in the entry-competitions for both composition and percussion, which was a big deal. That year, only two people were accepted for composition, one of them was me. I decided to take on a double major, which is rarely done. My dad told me that this was crazy, but I knew that I could do it and I did, I graduated with two degrees, one in composition and one in percussion. And I played the piano, in addition to that.

I heard about jazz through a friend from San Luis who played the alto saxophone, and who suggested that I go to the annual international jazz festival in Havana. I went, but at first I was not really impressed by anything, until I saw Richie Cole play with his group. This was in 1988. I think that seeing him play was the most liberating thing for me, ever. I remember that he was playing blues, he sang, and as I watched the pianist of the group play with that incredible amount of freedom, I knew that what I wanted to do was that, to play like that, to become a jazz pianist.

After school hours, students at the Instituto would get together for jam sessions and I started to attend them; I was dying to be part of that scene. The problem was that they had many percussionists already at the sessions, all of them great players, so there was no room for me. The only thing that was left was a piano because nobody could play it well enough. Then one day, out of desperation, I took the piano and I played for them. It must have worked really well because they kept asking me to return and play piano. That is how I became the pianist at the jam sessions.

I remember, this was the point when I made the conscious decision to become much better at the piano than I was at that point, I told myself that if I really want to become a pianist, I better do it well. I talked to my piano teacher who agreed to create a personalized program for me, because I did not want to quit the percussion program. And this is how it started. I put a lot of time in the piano…a lot of time, skipping meals sometime to secure a good piano to practice on.

At the time there was no jazz played in Cuba outside the yearly festival, so you had to get your jazz education through buying cassette tapes at the black market, where they went for a very high price. Our teachers at the Conservatory, who had a purely classical musical mindset, did not support us at all. For them, jazz was not music. Alongside the cultural bias, there was an element of politics in this, because Cuba being a communist country many of our teachers at the university were Russian or trained at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory of Music in Russia. These teachers saw jazz as a symbol of America, as the music of the enemy, some form of decay. But I persisted, I formed my own jazz-band and we started auditioning for the annual jazz festival in Havana and we got accepted to play, each year. That was great exposure, the international festival, as bands from other countries came, alongside the professional ones from Cuba. But my band was the only student band at the festival.

Jazz for me is freedom, it is free creative expression. Freedom, period. It is not that there are no rules in jazz, because there are. The point is really that within the structure of the rules I can choose a direction and interpretation for myself. You know, when you play a classical music piece, the closer you get to what the composer’s mindset was when writing it, the better your interpretation is considered to be. Your interpretation is judged by the original. In jazz, it is not like that at all. Jazz is freedom within a structure.

I started teaching music very early on. Musicians from Europe and from the United States were coming to Cuba to learn about our music and I was asked by my school to teach some of the courses offered to them. I taught Latin-jazz, piano, improvisation, salsa, things like that. I was one of the few who could teach this type of music and also have a strong classical foundation, so I had a lot of opportunities. This is how I met some people from the university at Philadelphia [Temple], and eventually that is how I came to the US, I was offered a teaching position at Asociación de Músicos Latinoamericanos (AMLA).

[Regarding the question of folklore and folk traditions in his music:]

My first album released in the United States is titled Incantations/Encantaciones (2003) and the songs Oguere’s Cha [based on a lullaby with mixed creole lyrics] and Negrita Prende la Vela [based on a Columbian folk song] are from that. It kind of reflects the feeling I had after I first arrived to America where everything is so divided [categorized], you know, they told me “well, if you are Cuban you play salsa, if you are from America you play jazz, if you play Cuban music it has to include drums”...everything felt very chopped up. And I have always known that this was not correct, that all the music of the Americas has the same roots, these divisions in music are actually divisions that we created, music itself is not actually divided.

So, when I composed the music for Incantations, I think that I was trying to meet certain expectations I felt were placed on me, as a Cuban, in a way. Like Oguere’s Cha has chachacha as its base, and there are other Cuban musical influences very present on that album, such as rhythms derived from the Santeria religion. The album has a lot of jazz, yes, but in my mind it is very Cuban. The original idea was to make something that was Cuban in the American sense, but now that you have asked me those questions about the role of the folkloric in my music I am thinking that the album, on the whole, might not even have come out that way, it is more like a composite. In [the song] Cacique, for example, I used a twelve-tone system, which is more of a classical base in a very modern compositional form, but then I decided to use a batá [a double-headed drum] to play the rhythm, to connect to the Cuban traditions in some way. Then when I created the melody I was thinking about what John Coltrane would play.

Then my next album was called The Source in Between (2008) and with this album I wanted to move beyond categories and show that the roots of jazz, Latin-jazz, and Afro-Cuban music are actually the same. In the title of the album, “Source” means the roots of music in the Americas. To give you an example: the first track on the album, which has the same title as the album itself, has no congas in it. For the last track of the album, I decided to use the same music, but I put congas in it. We did not even record the music again, I just took the same track and put the congas over it, just to show that even though the first one doesn’t have congas, those drums were in there all the time, inside the music.

I started thinking more and more along those lines, and my mission, in a way, became to create a form of music that does not have a line in between, I wanted to erase that line. Which of course creates a lot of problems when I try to promote my work, because I do not fit into the music industry categories, so it sort of becomes like while I am trying to erase the line, my music becomes the line itself, not because I want it to be that way or because I see it that way, but because that is how people see me. I do not fit into the box, so to say.

My album Cinque (released in 2018) was the product of many years of research, and of this progression in the way I think about music. It is also a return to my roots, to the Congolese environment that formed part of my childhood. I was already living in the US, in Philadelphia, when I started being interested in that [the musical tradition of the tambor yuka and its cultural context, the Congolese tradition, palo] and I wanted to really go back and research it, learn more about it. It was a lengthy process, I kept going back every year and talked to the people who still played those drums, I recorded them as they sang and played. It seemed important to me to preserve that because it is a form of music that has gone unnoticed, unlike rumba or Santeria, which are elements very popular in the jazz environment. I really wanted to preserve the music of my town, and to honor it in some way.

The first song I wrote for that album is Troubled Waters, which was a commission from Jazz at Lincoln Center, and the success of that piece was what inspired me to continue and create a larger body of work. I had this idea that I would take five countries/cultures from the Caribbean-islands, find their Congolese roots, and create a musical suite composed around that culture and music. I chose Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which actually adds up to four islands, because the last two are located on the same island. I travelled to each country and started doing research and started searching for stories that were similar to each other, old stories reflecting a similar past. I was reading a lot, listened to a lot of music, and then I started composing, putting the album together.

It is impossible to put the finished album within a category, you see. There is a lot of jazz in it, but there are a lot of other things as well. It is music, just music...perhaps the best way to describe it is to say that it is my form of jazz.

As for the personal side of the freedom-story [of Cinque], the stories from the slave era resonate with me, definitely. While slavery has not been directly part of my life, having grown up during the Castro era in Cuba, I have personal experience with questions of freedom and unfreedom. Those questions have not disappeared, they simply shifted. If anything, they are now relevant for the entire Cuban society.

[Regarding the question of academic musical curriculum in the United States]:

In the US, or actually in any other country that was colonized by Western European powers, the musical curriculum is largely based on their European notion of what music is, which is based on melody and harmony. Those musical elements are the focus of the curriculum taught in most academic schools in the US, the rhythm part is very superficially taught. This was true even in Cuba, up until a short while ago, we were not taught in the school how to incorporate rhythm. But that does not mean melody and rhythm are less important, it simply means that there are other elements to good music. If it were up to me, I would include rhythm to be taught extensively.

Another aspect that is missing, is a wider perspective that would teach students the origins of musical traditions from other places, not only the United States. When we talk about jazz, for example, what is being taught is that the roots were in New Orleans, in the Spanish Tinge piano style of Jelly Roll Morton, in ragtime, and things like that. But I would like us to go beyond that, to trace it further back, the way that Jelly Roll himself actually did, when he explained that the way he developed his Spanish Tinge piano style was that he used the syncopated bass pattern featured in the habanera, a French-based dance style developed in Havana, and then he put the blues on top of it. He took ingredients that had already existed and brewed his own coffee. I would like to see a tracing of those ingredients go further than the habanera or New Orleans-jazz, and even further than jazz itself, as jazz is already a synthesis of many elements. And most of those elements themselves are a synthesis, a result of collisions and fusions from earlier times. It is a long path with various forms of synthesis and reinvention along the way. I think that it is a path that we should show students as much as possible, so they can walk it, experience it, and then reinvent it, so they can find their own way.

Inspirations, acknowledgements

Beyond the sounds and silences of Cuban music and painting, beyond my Eastern European upbringing, my studies about Haiti, her people and her gods, the following inspired me to create this piece:

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past, Power and the Production of History (1995), in which Trouillot says: “The comparative study of slavery in the Americas provides an engaging example that what we often call the ‘legacy of the past’ may not be anything bequeathed by the past itself. [... T]he historical relevance of slavery in the United States […] is constantly evoked as the starting point of an ongoing traumatism and as a necessary explanation to current inequalities suffered by blacks. I would be the last one to deny that plantation slavery was a traumatic experience that left strong scars throughout the Americas. But the experience of African-Americans outside of the United States challenges the direct correlation between past traumas and historical relevance” (pp. 16-17).

Kapil Raj, Relocating Modern Science, Circulation and the Construction of Knowledge in South Asia and Europe, 1650-1900 (2006), in which Raj argues that rather than looking at knowledge as a given set of ideas that emanates from a pre-existing center and spreads in an unchanged (and unchangeable) fashion, the story of existing human knowledge is a story of collisions, additions, compromises and comings together, along shifting lines of dominance, adjustment, and accommodation. Alongside other authors whose work focuses on cultural and commercial connections in the Indian Ocean world, this book suggests considering circulation and exchange as the appropriate sites for the production of human knowledge.

Ildi Tillmann’s previous essay in JFBT was “From Hungary to Haiti: Unique Histories, Universal Stories.” She is an author and photographer who has been working for the last three years on a freelance multimedia project in Haiti, titled Lives in Revolution. The project seeks to take readers and viewers behind news media headlines and beyond the pity-provoking stories and images of the nonprofit industry, two sources of knowledge production that are prevalent with respect to Haiti. Ildi's photography has won several international photography awards, and her essays and fiction have been published in journals in the US and the Caribbean.

Prints of Ildi's Haiti photos are available through her website. Profits from sales of these photos will be shared 50/50 with the Haitian people with whom she works.

To learn more about Ildi’s work, please visit her website, subscribe to her Medium page, and follow her on Instagram.

Elio Villafranca is a Cuban-born composer, pianist, and cultural activist. He was classically trained in piano, percussion, and composition at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana, Cuba. Since his arrival in the United States, he has been working at the forefront of the music world, fusing classical, jazz, and the traditions of the African diaspora. Based in NYC, Villafranca is a jazz faculty member at The Juilliard School of Music, Manhattan School of Music, New York University, and Temple University in Philadelphia. He is a Steinway artist, a two-time Grammy nominee, a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow and the recipient of various prestigious awards. For more information or to contact Elio, please visit his website.

[1] This is not meant to overgeneralize about people living in North America, or their opinions. The goal is simply to point out that there is a contemporary attempt at a new form of moral and cultural imperialism, which originates from this part of the world. It is also worthwhile remembering that this race-essentialist approach to progress was neither characteristic of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s movement, nor of the artistic ideals of members of the Harlem Renaissance, bedrocks of black politics and culture in the US.

Another terrific humanistic essay / interview from Tillmann. A truly open mind.

Unsurpassed. Maximally worthwhile. All I would do is bow before the author and subject. And, to be honest, envy of wishing I had a talent like them.) TYTY.