DEI

REFORMING THE DEI REFORMS

MEI: Merit, Economics, and Ingenuity as a solution

Quinn Que

You will by now be familiar with the controversial organizational policy framework known as Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion or DEI. After all, Trump spent the first days of his presidency dismantling it in the federal government. You may (not yet) know of its oppositional counterpart: MEI. I’ll talk about both somewhat in this piece, but my focus will mainly be on the latter. In fact, I’ll discuss the original MEI proposal and then offer my own update to it. I should say at the outset that, if you’re looking for a long explainer of what DEI is and why it’s pernicious, I’m not doing much on the anti-DEI front today. Such articles have been done to death already, and I’m confident that you’ve read a few. I won’t reiterate those well trodden points of attack too much here.

Background on the fight: How did we get here?

The DEI framework is ostensibly about taking three closely linked values and institutionalizing them, essentially baking DEI into a given organization, often a school or a workplace, like one might add flavored filling to a pastry. Alas, the filling is rather disagreeable. Let’s look at the three prongs of the DEI trident. The diversity piece is about recruiting people of certain identity groups, specifically ones considered minorities or marginalized in society. Equity is about forcing certain results or norms, usually cashed out to be what academics call substantive equality, or more colloquially equality of outcome. This often means, in practice, giving undue advantages to people from the diversity groups, creating a kind of inverted caste system that favors so-called diverse people over non-diverse ones. Inclusion, which is probably the most euphemistically/obscurantistically titled prong of the three, is about changing organizational culture to be more in line with the ideas that DEI practitioners favor. This is presented as making the org culture more welcoming, but in practice it’s moreso making members of the org adopt certain political concepts as received wisdom. These ideas may include, but are not limited to cultural relativism, structural racism, the feminist theory of patriarchy, and more. Inclusion also tends to involve adoption of specialized language and speech codes, sometimes with banned word lists. All very Orwellian, but it’s easy to miss the insidiousness of it, especially the full extent.

DEI was born out of the affirmative action ecosystem, bolstered via government mandates like Barack Obama’s Executive Order 13583 of August 18, 2011 on “Diversity and Inclusion in the Federal Workforce,” and further fueled by Democrat-led political counter-signaling during the first administration of President Donald Trump. Within the last 10 years, DEI became the default rubric by which organizations choose their new additions (employees, students, etc.) and enforced unanimity of action and opinion on certain issues or policies. One can understand that there were good intentions at work here, even if they were also linked, increasingly and inextricably, with highly disagreeable political ideas that started in academia, wormed their way into professional life (especially human resources), and ultimately became overly salient in regular places like retail, hospitality, healthcare, and elsewhere.

Given all this, a backlash was inevitable. What came as a mild surprise, although perhaps it shouldn’t have, was the introduction of a competing framework that seeks to replace DEI with, depending on whom you ask, either pure meritocracy or empty sloganeering.

Merit, Excellence, and Intelligence, or MEI, is a loosely defined prescription to treat the illness of DEI. It suggests a focus on quality and qualifications over identity or lofty left-wing sociopolitical goals. Although it’s not explicitly conservative or per se ideological in the same way as DEI, the MEI push has an unmistakable reactionary bent. I say all this as someone who’s inclined, at least in theory, to support such an initiative. The problem with MEI is that it is fundamentally too simplistic, too self-flattering, and too stilted in its framing and goals. It would also be ill-fitted to slot into the DEI-shaped holes it seeks to fill.

For starters, let’s address the obvious: MEI is basically just three similar words slapped together. From the outside looking in, this might make sense, since that’s what DEI can seem like too. But DEI is actually a set of three distinct, yet interrelated prongs. Synergistic and holistic, but not necessarily redundant. Diversity is not the same as, nor does it imply, Equity. Inclusion sounds akin to both, but that too is being a bit shortsighted once we think on it for a few minutes. Yet MEI is basically just saying the same thing three times. Merit is about meritocracy, which is inclusive of excellence and intelligence. In fact, the biggest foot-shot of MEI is the needless decision to spell out the last part as one of the pillars. When one says MEI is about “Intelligence,” with the presupposition that DEI isn’t (or can’t be), they create space for an obvious rebuttal to the effect of, “Oh, so you’re saying DEI people are dumb? That’s racist!” It’s such an own goal, as they say in soccer for accidental points scored against oneself.

Then there’s the issue that just promoting meritocracy in recruiting could essentially amount, in effect, to either dismantling DEI with nothing to replace it—bad idea, nature abhors a vacuum—or replacing DEI with an ill-defined notion of just...meritocratically finding excellent and smart people. It’s hollow, almost cartoonishly so, and it’s a waste of the huge opportunity that properly replacing DEI could represent in various fields. Remember, DEI exploded and became a cottage industry within the last 5 to 7 years. It’s heavily informed by, and tied to, academia. It’s a prevailing orthodoxy in human resources. All that infrastructure to work with, and the current MEI proponents wanna fill it with “lol, just pick good people, done!” What a lack of vision.

The DEI industry and the ecosystem that spawned around it represents more than just an ideological dragon to be slain. There’s knowledge, manpower, and authority to work with. Even if we stopped funding the specific ideology, even if we fired, or stopped contracting with, the self-appointed experts of DEI, we’d still have HR teams and school admissions departments to wrangle. If one wants to replace DEI with something, let it be something good, something fit to the task and the environment DEI has operated in. Don’t just settle for less, it’d be such a wasted opportunity. But fear not, friends, I’ve got a plan.

An MEI That Works for Everyone

First things first, let’s fix that ridiculous list of words. The initials/acronym will work well enough, but like I said before, we shouldn’t have vague or intra-synonymous sounding terms in the full, spelled out framework. We’ll keep Merit for the M, since we do want an emphasis on meritocracy and quality. For the E, however, I’m thinking Economics, which I’ll explain below in a bit. And for the *I,* how about Ingenuity? It’s a good word, not at all superfluous, and makes this whole thing sound truly aspirational, rather than simply like a technocratic wishlist. These three prongs will be our logically flowing, parsimonious, and robust MEI trident. Internally consistent instead of internally redundant. In order to make real use of the DEI ecosystem that we want to replace with MEI, I think we should establish goals for a new framework beyond simply “don’t be DEI.” These will get us there. Now let’s dig in.

Merit

At the heart and the start of MEI is merit—a principle that individuals should be chosen based on their strengths, skills, intelligence, and overall qualifications. We must ensure that the most competent and qualified people rise to the top, driving excellence and innovation. It posits that we follow a clear, objective measure of success, where effort and talent are rewarded. This is arguably the most important prong of MEI, and fans of the original MEI configuration were right to metaphorically triple down on it. They simply were a bit misguided to think that literally tripling down made sense, especially from the outside looking in.

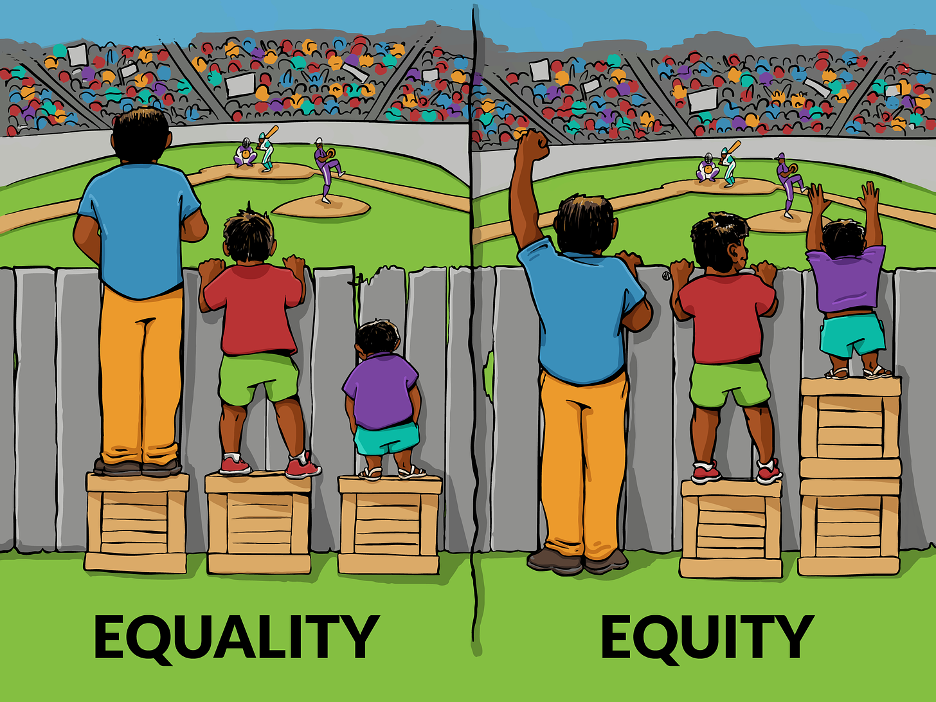

To those who might argue meritocracy doesn’t exist, or that it’s just a code for business as usual, I say, “open your mind (and your heart).” We can hire the best person for the job, or accept the best application for university, without overlooking deserving people from less successful backgrounds. Formal equality is literally a form of egalitarianism. There are activists who denounce the very notion of having standards, those who say formal equality is somehow oppression; yet that itself is a soft bigotry born of low expectations. I don’t think, as some Cultural Marxists in academia or HR seem to, that lowering/eliminating standards for recruits is analogous to giving apple-boxes to people who were born short (see the graphic above). Why? Because if Equity means lowering standards, the implication of the analogy is that I, and many other “marginalized identities” were born inferior. I don’t believe that. Because, amongst other things, I’m not a racist. So they can keep their metaphorical apple-box, thanks.

Economics (or Echelon)

This prong will probably be the most divisive, so I’ll say that upfront. Economics, which I’m parenthetically subtitling “Echelon” (as in social class), has as its focus two main sub-goals. One part is to find candidates who will be good investments, ideally by saving money and generating value for the organization. Economics looks at the cost-benefit analysis aspect of recruiting for schools, professions, and so on. Think of it like Sabermetrics in sports. Hiring is expensive, as you might have heard elsewhere. It’s better to keep that in mind and roll it into our criteria for acceptance.

The other big aim of the E here, as implied by Echelon, is to prioritize finding and uplifting prospects of lower class backgrounds. This would be, ironically, like a kind of affirmative action (or a kind of pseudo DEI), only done morally and sans race essentialism. When affirmative action was first being batted around in the 1960s, there were suggestions to do it on the basis of socioeconomic class rather than simple racial preferences. Martin Luther King Jr. himself was in favor of class-based affirmative action (albeit in addition to race-based). The notion of class-based initiatives, rather than simple racial preferences (along with later gender preferences and so on), obviously didn’t win out. Part of the reason why was, understandably and cynically enough, interference from the Black Elite, a middle class of African Americans that Karl Marx might have called a “bourgeois” class. They knew that they themselves and their children wouldn’t benefit from class-based affirmative action. Thus the idea was largely scrapped, and so it was that we ended up focused on immutable characteristics, even though the concerns we were ostensibly trying to remediate were material disparities in things like educational achievement, social status, and wealth. Elites keeping their lower-class equivalents down, a tale as old as time itself.

To me, the best part of the Economics/Echelon twin sub-goals is that they’re mutually inclusive. Finding the person with the highest ROI (return on investment) potential will often correlate with picking someone from a lower social class. These are smart, capable folks that typically won’t demand as much from an organization in terms of amenities, compensation, or overall perks and terms. They just want to learn and work, to make a name for themselves, and to create value for the org that’s smart enough to pick them.

Ingenuity

This is the most fun and flexible prong. Ingenuity could best be summed up as “innovate internally, and find innovative people.” It’s partly about changing the organizational culture, but mainly through an emphasis on finding and empowering unique people in new ways. It is therefore a far less doctrinaire means than the “Inclusion” piece of DEI. That orgs should pursue a sui generis strategy of recruitment might sound obvious, even cliché, but what’s particular about Ingenuity is the cultural piece.

Exceptional people don’t always love, let alone work well in, unexceptional organizations. So orgs should try to not only find someone who’s original, distinctive, clever, and/or creative, they should find what it is about these people or their thinking that’s worth implementing. Diversity is great in theory, especially when it’s diversity of thought, but only if it’s actually valued and maximized. “Think outside the box” is a nice saying, but worthless if you never live up to it.

Ingenuity is ultimately about being unorthodox. Organizations ought not to just tick a box, especially in some essentialist or identitarian sense, but to identify people who are different in truly useful ways, who can help solve specific problems, and yes, sometimes maybe even look less homogeneous than the rest of the org. Yet we must remember that the focus is always on the mind first, the body second.

Conclusion

Though there have been historic injustices, limits on participation or opportunity, and organizational shortcomings, I think it’s clear we didn’t necessarily need DEI. Or at least we didn’t need what it became, not in its current form. Yet we got it, and the ecosystem around it will likely live on in some form. If we are to replace it with something, let that something be substantive and efficacious. I’m open to MEI, especially as I’ve reimagined here. We need something real and we need it to work. I’ve laid out my vision of a more solid and reformist MEI, with Merit, Economics, and Ingenuity as the tines of the trident. This framework could save academia and the working world from many of its current DEI headaches. In addition, MEI could actually live up to the promise that all of its predecessors made and ultimately fell short of. I’m excited, and I hope you are too. If you’d like to discuss this further, hit me up about it. I’ll see ya next time.

Quinn “Edokwin” Que is a multimedia writer currently based in the urban boweries of the Southern United States. Originally an essayist and English tutor by training, he has branched out as a generalist writer of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. Most of his long-form articles are collected on his blog, the Edokwin Editorial, whilst frequent, miscellaneous musings are available via his prolific X account. He also occasionally does spoken word, social audio, and livestreaming. His primary areas of interest are culture, geekdom, humanism, media, morality, philosophy, and politics.

I can appreciate the need for an alternative framework in a power vacuum, but I'm always wary of these word fusions. For the Jacobins it was "Liberty, Fraternity, Equality" (among others). For the Bolsheviks, "Peace, Land, and Bread." And, for the Social Justice revolutionary, "Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion." Some may object that this is hyperbole, but I don't think it is. Something happens at the meta level, a quasi religious reaction, to far too many people that seem primed to respond to these movements. Even the early Taoists cautioned against the dangers of naming everything. So, I would suggest that to the extent this framework or a similar alternative is adopted, it should be held loosely.

Excellent! If we want MEI to apply for all kinds of jobs, not only the ones that need brilliant people, but the ones that need regular people, maybe the 'I"can be for "integrity". (Although I am not quite sure how to assess that in an applicant :))