Affirmative Action

THE END OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION IS AN OPPORTUNITY

True equality is now within reach

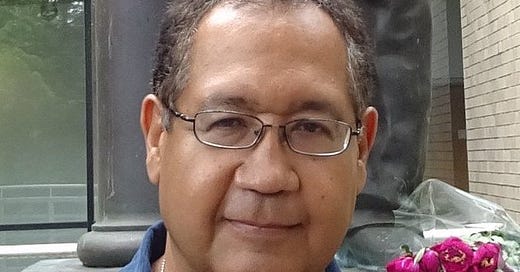

Michael Creswell

As expected, the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down the use of race as a factor in college and university admissions. This decision overturned longstanding legal precedent, which began in 1978 when Regents of the University of California v. Bakke established the constitutionality of affirmative action programs. Many Americans cheer this decision as long overdue. Former President Donald Trump said it was “a great day for America.” Others strongly disagree. President Joe Biden called the decision “a severe disappointment.” The decision also sparked a bitter exchange between Justices Clarence Thomas and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Debate on this issue will likely continue for years.

But despite the cries from some quarters that black people will be grievously harmed by the court’s decision, there are reasons to believe that the demise of race-based admissions, which is code for lower standards, could present a welcome opportunity.

One reason is that black students will now matriculate to colleges and universities that are best suited to their skills and preparation. Under affirmative action, two problems arose. One problem was that many black students were admitted to selective schools that presented challenges beyond their academic abilities (as measured by standardized tests like the SAT), and without sufficient preparation, a key marker of which is participation in Advanced Placement courses. The result was, not surprisingly, a mismatch between the school and the student. Sadly, many of these mismatched students switch to less competitive majors, graduate at lower rates than their counterparts, and face more post-graduation setbacks. Under affirmative action, black college students were more likely to need remediation than any other group, while black law school graduates failed bar exams at four times the rate of whites. Eliminating affirmative action ends these unnecessary harms.

A second and related problem was that for many black students who were in fact qualified for the institution, a number of them were less academically prepared than many non-blacks in their cohort. This discrepancy meant that many black students’ academic performance, as determined by GPA, trailed that of other ethnic and racial groups on campus. This persistent academic disparity creates lower confidence in black students’ academic ability generally. Even the most highly qualified black students who never needed affirmation action may be suspected of having been admitted under lower standards.

Despite the exaggerated claims of some, the end of race-conscious admissions will not prevent black people from receiving a college education. According to a Princeton sociologist, only one percent of black and Hispanic students are admitted due to affirmative action. Instead, most of these students will now matriculate to colleges and universities that more closely align with their academic abilities. For example, HBCUs could see increased enrollment. This improved alignment between school and student will likely result in greater academic performance by black students and higher rates of graduation. Going to a state school instead of an Ivy is nothing to be ashamed of.

The termination of affirmative action will also lift the cloud of doubt hanging over the heads of many black students concerning their academic qualifications. Everyone knows that many schools lower admission standards for some students. But even though many black students meet or exceed the standards, doubts about their qualifications can persist. The question, “Are they really qualified, or did they get in only because of affirmative action?” is asked by blacks and non-blacks alike. Such doubts can eat away at the self-esteem of even highly qualified, confident black students. Is that the best environment in which to get an education, one where not only others have qualms about your ability, but you may even share them yourself? Even the distinguished Yale law professor Steven L. Carter, who is black, experienced such concerns:

“I got into law school because I am black. As many black professionals think they must, I have long suppressed this truth, insisting instead that I got where I am the same way everybody else did.”

Carter is not alone; Michelle Obama reacted to the court’s decision by recalling her own uncertainties about whether she belonged on campus:

“Back in college, I was one of the few Black students on my campus, and I was proud of getting into such a respected school. I knew I’d worked hard for it. But still, I sometimes wondered if people thought I got there because of affirmative action. It was a shadow that students like me couldn’t shake, whether those doubts came from the outside or inside our own minds.”

Rather than setting black students back, the end of race-based admissions could encourage the black community to reach for greater heights. Throughout history human beings have adapted to new circumstances and changed conditions. This explains why humans have been able to not only survive but thrive in difficult environments. With sufficient motivation, black Americans will find ways to successfully cope with the end of race-based admissions. A successful adaptation will result in black students entering and succeeding in colleges and universities like other groups—without special treatment.

Doing away with race-based preferences could also help lower racial tension. Race-based admissions have recently caused tension between the Asian and black communities. Although Harvard University defends its affirmative action policy, an internal study conducted by this institution conceded that if it considered only academic performance, the number of Asian students would rise significantly, from 19 percent to 43 percent of the entire student body. (Harvard’s internal study is cited and discussed in a court filing by Students for Fair Admissions, Inc.) As it stands, Harvard sends a recruitment letter to Asian-Americans only if they score at least 250 points higher on the SAT than black high schoolers. Discriminating against one group in order to favor another group can only cause resentment. The best way to avoid this outcome is to practice a policy of even-handedness.

There are other benefits that could result from the end of race-based admissions. Knowing that black students are admitted to colleges and universities through their own merit and not because of their race will help build needed pride in the black community. This is no small thing. Pride is essential to any group trying to come from behind.

But there is no pride to be derived from being selected under lowered admission standards. That is instead simple condescension. For decades now, admissions committees have been saying, in effect, “You are not good enough, but it doesn’t matter because we will wink and nod and give you a pass.” True racial equality comes from performing on a par with other groups. It means competing under the same set of rules. Lowering the bar does the exact opposite: it enshrines racial inequality.

The Supreme Court’s ruling could also be an opportunity to redirect energy toward improving K–12 education. Waiting until age 18, the age when most students enter college and university, is too late to make up for years of poor academic preparation. Academic gaps become harder to close the later they are addressed. The time to confront academic deficiencies is well before students set foot on campus.

The end of race-based admissions will usher in changes in the short run. The number of incoming black students at elite schools will go down (though less prestigious institutions will likely not see much of a change, as they are not as selective in their admissions). But if black people see the High Court’s decision as an opportunity rather than as an injury, they have promising futures ahead of them.

Michael H. Creswell is Associate Professor of History at Florida State University, the author of A Question of Balance: How France and the United States Created Cold War Europe, and an executive editor at History: Reviews of New Books. A specialist on the Cold War, Creswell is currently writing a book that examines the increasing difficulties Americans have in communicating in socially and politically productive ways. He has published previously in the Journal of Free Black Thought here, here, here, and here.

The outcomes cited by Mr. Creswell are well-established and under-appreciated. Furthermore, they make logical sense. Similar findings have been discovered when women pursue STEM at women’s colleges rather than coed institutions, although for different reasons.

We would be happier all around if we sought human flourishing in a variety of forms, rather than obsessing about numeric representations in each racial, gender, and socioeconomic group. For every Black denied admission to an Ivy League university, there are 6-8 times as many Whites who also get that thin envelope as HS seniors.

Human beings pursue in-group racial preferences starting with marriage rates (>85%) and only change over long sweeps of time as individuals know and trust each other. Coercing outcomes is a temporary high with longer term shortcomings.

Mostly accurate, but I do fear that in some ways this could end up being even worse. The SCOTUS left open a loophole, which is that it's fine for a black student to talk about their race in their essay, and for the school to take that into account. Whereas previously, a black student might've not thought about race in their lives at all, but just "checked the box", now the same black student might think that they should foreground the role of race in their lives, as that's what will be, or was, front and center in the application essay. Paradoxically, we travel down a path of even more focus on racial identity . . .