The Free-Thinker: James McCune Smith, M.D. (1813-1865)

Pioneering African American physician, author, and intellectual

American History

THE FREE-THINKER: JAMES McCUNE SMITH, M.D. (1813-1865)

Pioneering African American physician, author, and intellectual

Amy Cools

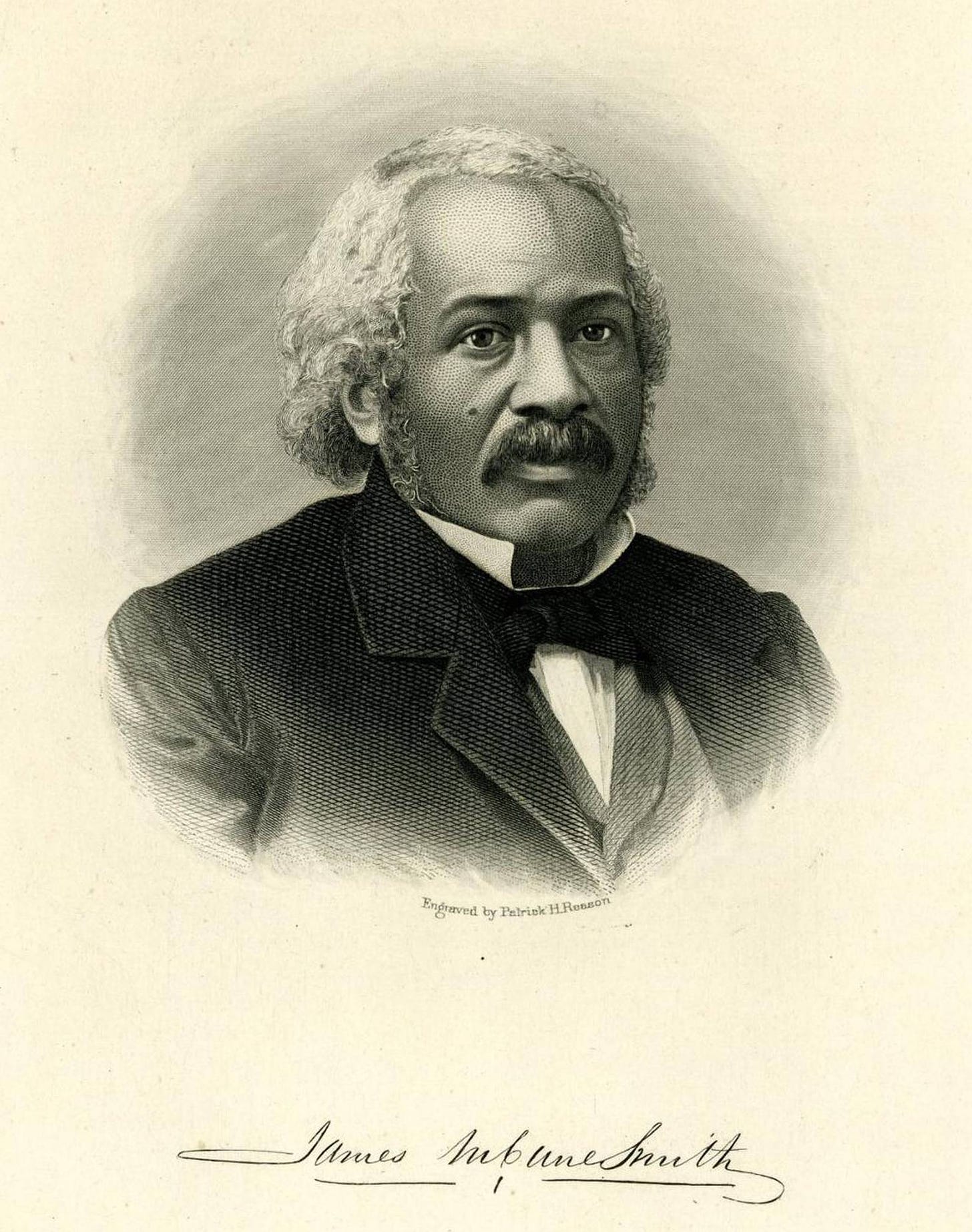

James McCune Smith was a pioneering physician, author, intellectual, anti-slavery and human rights activist, and community leader in nineteenth-century New York City. Born to legally enslaved, “self-emancipated” (as McCune Smith described her; the details of how she emancipated herself are still unknown) Lavinia Smith in 1813, he managed to achieve something that no one else had achieved before: he was the first African American to practice medicine with a medical degree. Largely forgotten today, McCune Smith is remembered for this alone, if at all. Yet as interesting and important as this groundbreaking feat was, McCune Smith’s life was extraordinary in countless other ways.

McCune Smith was born into circumstances that would have made it extremely unlikely that he would go on to achieve the many things he did. Since his mother had left her native South Carolina still legally enslaved, McCune Smith probably shared that legal status when he was born. He almost certainly never met his father; his father certainly played no role in raising McCune Smith. McCune Smith’s hardworking mother and supportive community, however, recognized his evident intelligence and made sure he received an excellent education from an early age. After graduating from the African Free School in 1827, he continued a rigorous course of study centered on the classics, sometimes formally but more often under the guidance of tutors and mentors. For a year or two, McCune Smith also worked full time as a blacksmith’s apprentice but never abandoned his scholarly pursuits. His dedication and skill led prominent members of the community to help him obtain admission to the University of Glasgow after he was denied entry to New York institutions of higher learning on account of race. McCune Smith earned his bachelor’s, master’s, and medical degrees there (BA, 1835; MA, 1836; MD, 1837). His five years in Europe as a student, anti-slavery activist, and traveler was an adventure that profoundly affected his life and his views of the world.

Upon his return to New York City in 1837, McCune Smith became the preeminent African American intellectual of the nineteenth century, as friends and contemporaries such as Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, and William Cooper Nell attested. With his three university degrees, he was the most formally educated black American of his time, as John Stauffer describes him. McCune Smith can be seen as the African American community’s answer to Thomas Jefferson: a polymath who wrote eloquently and masterfully on a wide range of subjects, from several sciences to political philosophy to classical studies to race theory to history and much more.

For example, McCune Smith made significant contributions to the emerging fields of anthropology and race theory, as well as to his professional field of medicine. McCune Smith’s scientific rebuttal of Jefferson’s theories on “black” and “white” races in the latter’s Notes on the State of Virginia is one example, and is among his most powerful works. While others, such as the fiery and eloquent African American abolitionist David Walker, had previously and effectively rebutted Jefferson’s racist scientific theories, McCune Smith was the first African American scholar with advanced credentials and long-established expertise in anthropology to do so; in fact, his expertise and array of scholarly credentials far surpassed Jefferson’s own. The work in question, his 1859 article “On the Fourteenth Query of Thomas Jefferson's Notes on Virginia,” is a foundational work in American anthropology. He demonstrated, among other things, that—contrary to Jefferson’s views—the physical traits that could be observed in “black” and “white” people were not universal, fixed, or arrangeable in a hierarchy of desirability. Rather, there was a great deal of overlap in physical traits possessed by people popularly designated as different “races;” tendencies of populations to possess such traits changed over time and depending on circumstances such as climate and geography; and those traits that people did possess tended to be beneficial in different ways and so could not reasonably be called better or worse. Jefferson, McCune Smith concluded, was not motivated by the interest of the true scientist to understand the world as it is; rather, he just another one of those self-interested “Learned men, [who,] in their rage for classification and from a reprehensible spirit to bend science to provoke popular prejudices, have brought the human species under the yoke of classification, and having shown to their own satisfaction a diversity in the races, have placed us in the very lowest rank.” When it came to the slave-holding Jefferson, the motivation for doing so was self-evident. Indeed, McCune Smith believed that the “rage” to come up with race classifications and to assign people to them was almost always harmful, whatever the motivation.

From his deep studies in anthropology and world history, McCune Smith developed other theories which challenged other prevailing notions of race, particularly of the “black race.” For one, he did not believe there was any such thing. Rather, Africa was a huge continent that contained a vast diversity of ethnicities and populations (he used the term "race" to refer to concepts like these) which could in no reasonable, evidence-based way be lumped together and identified as one or even a few races. This was just as true of peoples of African descent all over the world, including African Americans, who he believed had come to be a new, indigenous, American ethnicity.1 This ethnicity had come about in the same way as all other ethnicities and populations of the world had always emerged: through the movements of people, the mixing or “amalgamation” (as it was then often called) of populations with different characteristics, and the influence of climate and geography on physical traits. While McCune Smith read Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and wrote about it not long after it was published—he appears to be the first African American to have done so—he, like Darwin, never came quite to understand the mechanism by which climate and geography influenced tendencies to exhibit certain physical traits in populations. (The science of genetics was still in its infancy; there it no evidence yet found which reveals that McCune Smith read Gregor Mendel’s work on rules of heritability.)

McCune Smith was also a pioneering author in medicine; for example, he was the first African American to have published in European and American medical journals. Among these writings were letters to the editor of a British medical journal, written when he was just out of medical school, forcefully arguing that a treatment for gonorrhea administered and promoted by a famous, influential Scottish physician was both painful and ineffective. As evidence, McCune Smith cited his personal experience working with patients at a charitable hospital for indigent women and girls suffering from venereal disease, as well as the hospital records. (McCune Smith’s work at Glasgow’s Lock Hospital fulfilled part of the clinical experience required for his medical degree.) The fact that McCune Smith was willing to risk his own budding career by publicly, fearlessly criticizing a powerful and influential physician on behalf of a marginalized and abused group of people is a perfect example of how he used his pen, his expertise, and his keen intellect to help improve the lives of others throughout his life.

McCune Smith’s writings were not only related to science, medicine, and history, nor was his authorship primarily directed at fellow professionals and intellectuals. He was a pioneer in journalism as well, playing a key role in the foundation and development of the early African American press. Whether as a regular contributor, a correspondent, or a co- or acting editor, McCune Smith wrote articles and essays on a vast array of subjects. For one, he was one of the few chroniclers of the lives of working-class African American New Yorkers at a time when most authors found their stories to be not sufficiently respectable or worthy of admiration, emulation, or even interest. With these and other essays, as Henry Louis Gates, Jr. argues, McCune Smith founded the genre of African American experimental literature. His vibrant writings for the African American press brimmed over with humor, pathos, wordplay, argumentation, anecdotes, gossip, sarcasm, anger, nostalgia, religiosity, prophecy, and/or triumph. As we have seen, he was an activist author as well, using his medical, scientific, and statistical expertise to disprove and discredit proslavery arguments, both in the African American and the mainstream press.

Though the written word was central to McCune Smith’s life, it was also a life of action. Almost immediately upon returning to New York, he became an entrepreneur, founding a successful pharmacy which he owned until nearly the end of his life. He also dealt in real estate. Between these and his thriving medical practice, McCune Smith became one of the wealthiest African American New Yorkers of his era. His professional and moneymaking ventures gave him the financial security to become a community leader and benefactor. He was the attending physician of the Colored Orphan Asylum for over twenty years, first as a volunteer and later for modest pay, all the while promoting its mission and fundraising for it. He dedicated himself to the cause of education as well, co-founding the New York Society for the Promotion of Education Among Colored Children and supporting local African American schools in myriad ways. He fought against discriminatory suffrage laws in New York State and segregation in New York City public transportation. When the Civil War came, McCune Smith supported efforts to enlist African Americans in the Union Army.

McCune Smith was also a hardworking and fierce abolitionist. When he moved to Britain to undertake his studies there, he immediately immersed himself in the abolitionist community. He was a founding member of the Glasgow Emancipation Society and would go on to be an active member—and sometimes a co-founder—of at least one abolitionist society for the rest of his life. McCune Smith was as fearless an advocate for the anti-slavery cause as he had been for the poor women he served in that Glasgow hospital, and just as willing to vociferously criticize the powerful and influential in that arena. For example, McCune Smith often acted as a gadfly to the American Anti-Slavery Society. Though he had been an acolyte of its founder William Lloyd Garrison and a devoted member of the Society, he came to observe over time that many Garrisonian principles and practices had come to be, or appear to be, more about making white abolitionists feel good about themselves than about helping African Americans improve their condition in concrete, practical ways. McCune Smith was never afraid to point out examples of this whenever he observed it was happening or heard it might be, making him a sometimes controversial figure in the abolitionist movement.

All the while, McCune Smith and his wife Malvina Smith, née Barnett, raised a large family. Tragically, they lost at least five children. Five, however, survived to adulthood and went on to live long lives. The Smith family was at the center of interconnected social, professional, economic, activist, religious, and beneficial African American networks in New York City and beyond; one of these linked communities in New York City and San Francisco.

Though widely known and lauded in his own time, McCune Smith has been largely forgotten since at least the late nineteenth century. This may be partially due to his early death in 1865, aged only 52. For reasons still unknown, neither his wife, nor his children (most of whom were very young when he died), nor any of his friends or colleagues are known to have collected and preserved his papers—or, if they did, they were subsequently lost. The historical amnesia concerning McCune Smith may also be due to the fact that no one wrote a full biography soon after his death, though at least one prominent African American, Philip A. Bell, called on others to do so. (Bell had moved to California and so could not access McCune Smith’s papers, so he called on McCune Smith’s friends on the East Coast to write the biography.) However, the closest thing to an early biography of McCune Smith that was written was a series of obituaries and book chapters. They richly attest his friends’, admirers’, and colleagues’ recognition of his myriad accomplishments and historical significance. However, these biographical tributes to him were incomplete, as are all published works on McCune Smith up to the present time. (Stauffer’s works on McCune Smith represent the most in-depth published studies of him.)

But these don’t appear to sufficiently explain why McCune Smith continued to suffer from scholarly neglect. After all, for example, his fellow pioneering African American scientist Benjamin Banneker was also widely forgotten, almost all of his papers lost, and details of his life even harder to find, yet he is the subject of many full-length biographies and has come to be widely remembered. There are things I’ve come across during the course of my work on McCune Smith that have led me to suspect—though I can’t demonstrate it firmly enough to make it more than a justified suspicion—that McCune Smith has always been a bit too controversial, too free-thinking, too outside-the-box, too politically inconvenient at any given time—even more so than his likewise fearless, complicated, often controversial friend Frederick Douglass—for authors to be willing to present a full, unvarnished account of his life and thought.

Whatever the case, McCune Smith had long been a parenthetical in African American history, selectively lauded for specific accomplishments, or discussed at length only within relatively narrow contexts. There continues to be no published work that presents McCune Smith in all his fascinating complexity. However, and encouragingly, contemporary scholars and the wider public are increasingly coming to appreciate more fully the true extent of McCune Smith’s historical importance and his influence on other thinkers, notably Frederick Douglass. I hope that my own work will also significantly contribute to restoring McCune Smith to the forefront of historical memory where he belongs.

Amy M. Cools, PhD, is a historian, author, researcher, and educator who, among other things, wrote the first finished, book-length monograph dedicated to the extraordinary life of James McCune Smith: “The Life and Work of James McCune Smith (1813-1865)” (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021). She writes a Substack on McCune Smith and is working on a biography to be published by the University of Georgia Press, as well as authoring or contributing to many other works that feature him, including journal articles, conference papers, presentations, videos, and more. You can find Cools’ many projects through her website and follow her on Twitter.

This is why this article uses the term “African American” rather than “black” or “Black,” in homage to McCune Smith’s theory of African American indigeneity and the fact that he opposed theories such as Pan-Africanism, in his time often called “black nationality.” He did routinely use the term “black,” but appears to have done so generally as a commonly used descriptive term rather than in the essentialist way it’s still often used today.

When we heard stories like these when I was young (1940's to early 1960's), we marveled at how so many slaves had "overcome." In those days, "overcome" was the word most associated with Blacks. Today, I think the most prevalent left wing characterization is "helpless victim." One should not confuse the ability of some to "overcome" to mean that society in general was not predatory, trying to keep everyone in their places. Nonetheless, the subconscious lesson we absorbed was a lot of Blacks were some how super heroes. Today, the subconscious lesson is that Blacks are whiners looking for handouts in the form of reparations. If I have to chose between stereotypes, I select the strong hero over the weak victim.

Personally, I prefer to treat each person as an individual on their character and not their race, gender, ethnicity, etc. But ,when the Woker stereotype of all Blacks as angry victims is forced on me each day, I have to admit that it does invade my mind, making it harder to see the individual.

This is yet another example of why JFBT is an excellent resource. Thank you for sharing this absorbing tribute to Dr. McCune Smith and for bringing him what is clearly long-overdue recognition. I now want to read Dr. Cools' further work on his distinguished life, and I hope it finds a wide audience.