The Progressive Myth of Racist Police Shootings

If there's racial bias in policing, it's not obvious in lethal force

Policing

THE PROGRESSIVE MYTH OF RACIST POLICE SHOOTINGS

If there's racial bias in policing, it's not obvious in lethal force

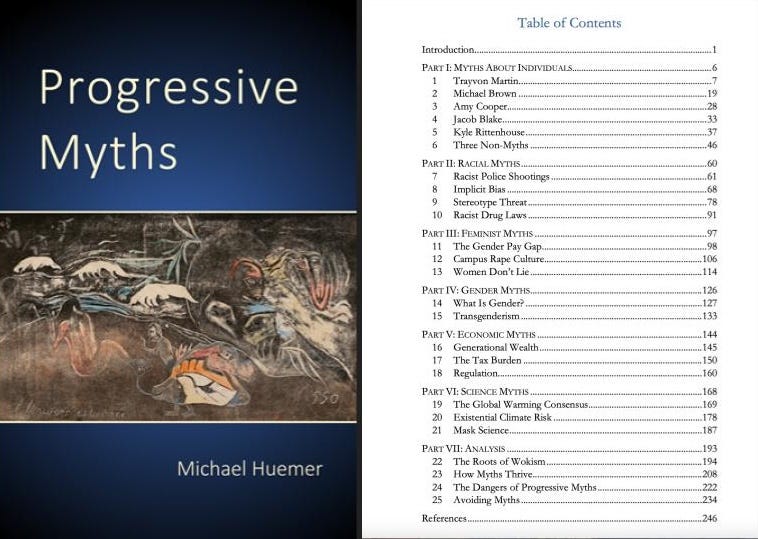

Editors’ note: This is an excerpt from Michael Huemer’s new book, Progressive Myths. Here are the cover and the table of contents:

The Myth

Many unarmed black people are shot by American police every year. Blacks are regularly killed by police due to racism.

Examples of the Myth

It is hard to find published sources that directly state the first part of the myth, concerning unarmed black men, though there are many sources that devote extensive attention to police shootings of unarmed black men while ignoring victims from other races.

In 2021, Skeptic magazine published survey results indicating people’s answers to the following questions:

Q1: “If you had to guess, how many unarmed Black men were killed by police in 2019?” (Available answers: About 10, about 100, about 1000, about 10,000, more than 10,000.)

Q2: “If you had to guess, in 2019 what percentage of people killed by police were Black?” (Respondents could choose any number from 0 to 100.)

In answer to Q1, 29% of people answered “about 1,000” or more (1,000: 19%; 10,000: 6%; over 10,000: 4%). In answer to Q2, the average estimate was 48%. (See further here.)

This doesn’t tell the whole story, though. The answers differed greatly by political orientation. Respondents who self-identified as “liberal” or “very liberal” were much less accurate than moderates or conservatives. Among liberal or very liberal respondents, nearly half (46%) thought that the number of unarmed black men killed by police was about 1,000 or more. This same group on average estimated that 58% of people killed by police were black.

Misconceptions were correlated with trust in the media—people who reported greater trust in the media were more misinformed about police shootings. This may be because media sources give misleading impressions about this particular issue. Alternately, it may be because “racist police shootings are a huge problem” and “the mainstream media are trustworthy” both have independent appeal to liberals.

Concerning the second part of the myth, that police killings show racial bias: The main argument for this is that a higher percentage of the people killed by the police are black than the percentage of the general population who are black:

Police disproportionately shoot and kill black Americans … black Americans were twice as likely to be shot and killed by police officers, compared with their representation in the population.

—ABC News

Black people, who account for 13 percent of the U.S. population, accounted for 27 percent of those fatally shot and killed by police in 2021…. That means Black people are twice as likely as white people to be shot and killed by police officers.

—NBC News

In 2013, three radical Black organizers—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi—created a Black-centered political-movement-building project called #BlackLivesMatter in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, George Zimmerman. […] We are working for a world where Black lives are no longer systematically targeted for demise.

—Black Lives Matter website

Reality

There is evidence that American police are unnecessarily violent. However, that is not my topic here. My topic here is whether police violence shows a widespread racial bias.

How often are unarmed black people killed by police?

Start with the number of unarmed black people killed by police. Again, half of liberal respondents estimated this at 1,000 or more for 2019. The correct figure was 36. (The total number of blacks killed by police in that year was 286, of whom just 36 were unarmed, 32 men and 4 women.) In the same year, police killed 54 unarmed white people (46 men and 8 women).

Does this still represent a major problem? Bear in mind that this was in a country of 330 million, which included 47 million blacks. It would not be shocking if, of 47 million black people, a total of 36, despite being unarmed, did something sufficiently threatening to cause them to be killed by police. In any case, the risk of this happening to a given black person is extremely small; they are literally more likely to be struck by lightning.1

The racial disproportion

Let’s turn to the total numbers of blacks and other Americans (whether armed or unarmed) killed by police. The statistics in the quotes above are accurate, based on the best available data: Blacks comprise about an eighth of the population but a quarter of the police shooting victims. Hence, you are more likely to be shot if black than otherwise. Does this indicate racism?

Consider another, even more shocking disproportion: Males make up only 50% of the population but 95.5% of the police shooting victims. Men are thus twenty-one times more likely to be shot by police than women. One could claim that this indicates an extraordinary degree of sexism, many times worse than the racism shown by police departments.

But most of us would reject this inference. To determine whether the shooting statistics indicate sexism, we must first consider such things as: How often do police make contact with male suspects? How often do men commit violent crimes, compared to women? How often do men commit violence against police officers, compared to women? Those questions would be relevant because they are proxies for the tendency of men to engage in threatening behavior toward police of the sort that could plausibly lead to a violent police response even in the absence of sexism. As it turns out, about 88% of all murderers and nearly all cop-killers are men. In 2013-14, for example, there were 66 men who killed police officers and one woman who aided her husband in killing a pair of police officers.

This would undercut the narrative of anti-male bias among police. Police may well be killing too many men, but we cannot infer sexism, since the gender disparity can as well be explained by greater numbers of aggressive male suspects as compared to females.

An exactly parallel point applies to the racial disparity. To assess the amount of racial bias, we need to consider such things as number of police contacts, violent crime rates, and rates of violence against police officers.

Begin with numbers of police contacts. Usually, when police make contact with a suspect, this is because a member of the community has called the police to report some apparent criminal behavior. These community members usually give a description of a suspect whom they believe to be committing or about to commit a crime. As it turns out, the racial composition of the group of suspects reported to the police by members of the community matches the racial composition of people shot by the police, leaving no evidence of racial bias on the part of the police.

You could hypothesize that racism by members of the community causes them to disproportionately report black people to the police. But the simpler explanation is that the higher rates at which black individuals are reported to the police are due to the higher crime rates by black individuals.

Apropos of that, recall that, per the quotations above, blacks comprise about 13% of the U.S. population but 27% of police shooting victims. However, blacks also comprise about 40% of murderers in the U.S., and 43% of cop-killers. Therefore, just as in the case of the gender disparity, the racial disparity in police shootings could plausibly be explained by a disparity in threatening behavior. It’s still possible that racism plays a role, just as it’s still possible that sexism plays a role, but the statistics give us no reason to posit racism or sexism. If anything, the statistics suggest a pro-black bias by police, since the rate at which blacks are shot by police is disproportionately low compared to the rate at which black people kill police officers.

Experimental evidence

The above sort of evidence has limitations. The database of homicides committed by the police does not have information about all the aspects of suspects and their behavior that may have influenced a decision to use lethal force. In brief, one cannot tell how threateningly each suspect was behaving.

Experimental evidence may address this shortcoming, since a laboratory experiment can control essentially all plausibly relevant factors other than race. This was the task of Lois James et al.’s (2016) study, which observed police behavior in simulators of the sort used during police training. The simulations involve video enactments, using actors, of the sorts of scenarios that police often encounter that have a risk of leading to a shooting. Sometimes, the suspect in the video pulls a gun and shoots at the camera; other times, the suspect pulls out an innocuous object such as a wallet. As the scenario unfolds, officers must decide whether and when to draw their guns and shoot at the suspect in the video. For the experiment, officers were equipped with Glock 22’s (like those used in many police departments), modified to emit infrared light rather than shooting real bullets, to detect when and where officers had shot.

Researchers prepared two versions of each of several scenarios: a version using a white actor, and a version using a black actor with everything else held the same. The purpose was to test whether officers would be quicker to shoot at black suspects.

This sort of experiment admittedly has its own limitations. Since officers know that they are not in any genuine danger, they may not react in the same way that they would in real life (even though they were instructed to do so). Nevertheless, the simulations were highly realistic, subjects showed signs of immersion, and simulations of this kind are widely taken to be the best way of preparing for real-world encounters. If officers were quicker to shoot black suspects in the simulations, progressive commentators would surely be quick to cite this as powerful evidence of racism, and rightly so.

In fact, the reverse turned out to be the case. In the scenarios in which the suspect pulls a gun, officers took 1.1 seconds to shoot if the suspect was white, and 1.3 seconds if the suspect was black. In scenarios in which the suspect pulls out a harmless object, officers wrongly shot the suspect 14% of the time if the suspect was white, and only 1% of the time if the suspect was black. This dovetails with the other evidence cited above for a pro-black or anti-white bias in police shootings.

Objections

How could there possibly be an anti-white bias in police shootings? That’s ridiculous.

Reply: The most likely explanation is an effect of media coverage and public attention. In recent years, enormous attention has focused on shootings of black suspects, which causes problems for the police department and the individual officers involved. By contrast, the other three quarters of police shootings, which are of non-black suspects, receive almost no attention. Thus, police officers are much more reluctant to shoot black suspects than suspects of other races.

This is supported by the statements of actual police officers. In 2015, a white Birmingham police detective was attacked by a black suspect, pistol whipped with his own gun, and left unconscious and bleeding on the ground while the suspect drove away. The detective later explained that the suspect was able to do this in part because the detective had hesitated to use force. “A lot of officers are being too cautious because of what’s going on in the media,” he said. “I hesitated because I didn’t want to be in the media like I am right now.” Another cop in the same police department explained that police are “walking on eggshells because of how they’re scrutinized in the media.”

Perhaps this is as it should be—if you could be deterred from using deadly force against someone by fear of your actions’ being scrutinized, then you probably should not use deadly force against that person. Granted, this entails some risk to officers, as the above case illustrates. But perhaps the risk to officers is worth it to reduce the risk of unnecessarily killing civilians.

In that case, the problem is that the media don’t scrutinize shootings of white, Asian, Hispanic, or other non-black suspects. Fewer people would probably be killed if they did.

This doesn’t address all other forms of racial bias in policing or the justice system.

Reply: That’s right, it doesn’t. The above discussion is only about homicides by police. This is worth addressing because it is the most momentous action taken by police or the justice system, as well as the most discussed. This issue was the cause of the protests and riots in many American cities in the last few years.

The hypothesis cited in reply to Objection 1 is consistent with the possibility that other aspects of the justice system show more racial bias, since they are much less scrutinized by the media and the public. If police rough up a suspect on the street, or a judge hands out an overly harsh punishment, there will normally be no public scrutiny. This is also consistent with Roland Fryer’s well-known (2019) study, which found that police are more likely to use nonlethal force against minority members than against whites, but not more likely to use lethal force. An obvious explanation for the difference in nonlethal force is that police officers engage in racial profiling.

Michael Huemer is a professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He is the author of more than eighty academic articles in epistemology, ethics, metaethics, metaphysics, and political philosophy, as well as about twelve amazing books that you should immediately buy. Check out his website and his Substack, Fake Noûs. Buy Progressive Myths on Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

400-500 Americans are struck by lightning per year, and 79% of the fatalities are among men. I don’t have lightning strike statistics by race, but assuming that lightning is race neutral, the average black person’s risk of being struck should be about 1.3×10-6, while their probability of being unarmed and shot by police is about 7.7×10-7. For black men, the probability of a lightning strike is probably about 2.2×10-6 (given that men are about four times more likely to be struck than women), while the probability of being shot by police while unarmed is about 1.5×10-6 (32 out of 22 million black men).

Roland Fryer is best known for two things: 1) The very meticulously conducted research(spanning multiple years) on thousands upon thousands of data points not only from police precincts in different states, but also FBI and WaPo databases. 2) Being persecuted and having his career threatened by Harvard for finding a conclusion that the Woke Aristocracy find offensive. I guess they were pissed that he used resources afforded him, only to find the “wrong conclusion”.

He’s also done amazing work in development of young minds with alternative education methods and sources.

Roland Fryer’s story is yet another example of the “burn the heretic” politics of the progressive left.

Data-led analysis that keeps the focus on a clear hypothesis and derives analytically defensible conclusions, as opposed to ideological viewpoints, is essential if we are to get beyond the endless destructive discussions in otherwise greatly biased media and academic coverage. As the author notes, the outcome here suggests neither that policing is perfect in any way nor that the violent circumstances in which police are forced to operate permit neat and better choices in the moment.