American Independence

WHAT TO US NOW IS THE FOURTH OF JULY?

An emancipatory revolution

Jake Mackey

Editors’ note: This essay is a republication with minor edits of last year’s July 4th post.

1. America the Oppressive?

America: A country founded on the genocide of Indigenous people, the enslavement and genocide of African people, and thereafter a spin cycle of racism and xenophobia, including but not limited to the Chinese Exclusion Act, Operation Wetback, Jim Crow, the Muslim travel ban, the Department of Homeland Security.

This is how Regina Jackson and Saira Rao define America in the glossary to their best-selling book, White Women: Everything You Already Know About Your Own Racism and How to Do Better.

Expressing sentiments such as these about America’s founding and historical trajectory on college campuses and in respected newspapers will get you rewarded with finger snaps and perhaps even a Pulitzer Prize. Of course, Jackson and Rao’s understanding of America is not without a basis in truth, and I do not wish to sidestep that. The arrival of Europeans was a catastrophe for Native Americans. Slavery in the American colonies and later the young United States was a moral abyss. And so on.

Ultimately, however, the facts about American evils such as slavery must be contextualized within the fuller story about American struggles against such evils, such as anti-slavery, which will be our focus in this article. Sean Wilentz likes to quote the great African American historian, Benjamin Quarles, who wrote in 1977—

The institution of slavery cannot be accurately appraised or understood…without careful attention to a concomitant development and influence—the crusade against it. The anti-slavery leaders and their organizations tell us much about slavery and, of hardly lesser importance, something about our character as a nation.1

If our nation’s founding was characterized by slavery, it was also characterized, like no nation before it, by anti-slavery.

Unremittingly pessimistic framings of the sort employed by Jackson and Rao operate on the premise that if you portray America as having “oppression coded into its very DNA,” you somehow thereby inspire people to fix it. Yet it seems equally plausible that if you portray their country as unredeemable, you decrease the likelihood that citizens will have any reason to hope that their efforts can contribute to improving it. As George Packer recently put it, “Progressive scholarship,” not to mention popular work like Jackson and Rao’s, “makes progressive politics seem hopeless.”

Yet America is not defined and differentiated from other countries by its history of oppression. That history is what made colonial America and the early United States similar to other societies. What is unique about America is that it formulated an ideological repudiation of oppression and became the first society ever to foster an organized and principled movement for the abolition of slavery.2 As David Brion Davis put it, “Although slavery was nearly as old as human history, this was something new to the world.”3 This movement is coterminous with our founding. It arose from the ideals of equality and liberty that motivated the Revolution. It is not slavery, which has existed practically everywhere, but American ideals and the American legacy of anti-slavery that make America unique. These ideals and this legacy are our birthright. They are what we celebrate on the Fourth of July.

2. The Declaration of Independence, Revolutionary Ideals, and Abolition

The canonical statement of Revolutionary ideals is, of course, the Preamble to the Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed….

The Declaration goes on to refer to British rule as “absolute Despotism” and to the power of the “King of Great Britain” as “absolute Tyranny.”

Equality and liberty, the core Revolutionary ideals that underlie these words, are intertwined. Equality amounts not to sameness in skills, talents, or ability but to equal moral worth, reflected in, as Danielle Allen argues in Our Declaration, a social arrangement in which “neither of two parties can dominate the other.”4 Equality is thus required for liberty, insofar as liberty amounts to non-domination.

According to Bernard Bailyn, that “liberty was precarious” was a fact which the colonists had discovered in the course of a century and a half of dealings with Britain. The Revolution was motivated by the colonists’ acquired mistrust of “privilege, ascribed to some and denied to others mainly at birth,” which was corrosive of equality, as well as by their fear of the arbitrary “misuse of power,” which was destructive of liberty.5 In this light, we see the full force of the Declaration’s denouncement of tyranny, the arbitrary domination of one party by another.

The felt concern to secure liberty against misuses of power and privilege issued in the assertion of concepts such as the Declaration’s “unalienable Rights” and “consent of the governed,” and in the eventual creation of institutions such as “written constitutions; the separation of powers; bills of rights,” and so on,6 designed to protect individual liberty from the arbitrary exercise of power and privilege.

These Revolutionary preoccupations permeate the literature of the period preceding and following the Declaration and were applied to the question of slavery by authors white and black. Thus, James Otis, a white Massachusetts lawyer, in his Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved, written in response to Parliament’s Sugar Act of 1764, asserted, “The colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed all men are, white and black.”7 Similarly, in 1767, the internationally influential French-born Pennsylvania Quaker and abolitionist, Anthony Benezet, in his abolitionist treatise, A Caution and Warning, inquires scathingly:

At a Time when the general Rights and Liberties of Mankind…are become so much the Subjects of Universal Consideration; can it be an Enquiry Indifferent to any, how many of those who distinguish themselves as the Advocates of Liberty, remain Insensible and Inattentive to the Treatment of Thousands and Tens of Thousands of our Fellow-Men, who, from Motives of Avarice, and the inexorable Decree of Tyrant Custom, are at this very Time kept in the most deplorable State of Slavery?8

Here the themes of natural rights, liberty, and tyrannical power are applied not only to the Revolutionary cause, as was usual, but also extended to the cause of abolition. Benezet chides the colonists for failing to include in their advocacy for liberty those whom they themselves were depriving of liberty. Benezet would go on, in 1775, to organize in Philadelphia the first abolitionist society in world history, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage (reorganized in 1784 as the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and eventually led by Benjamin Franklin).

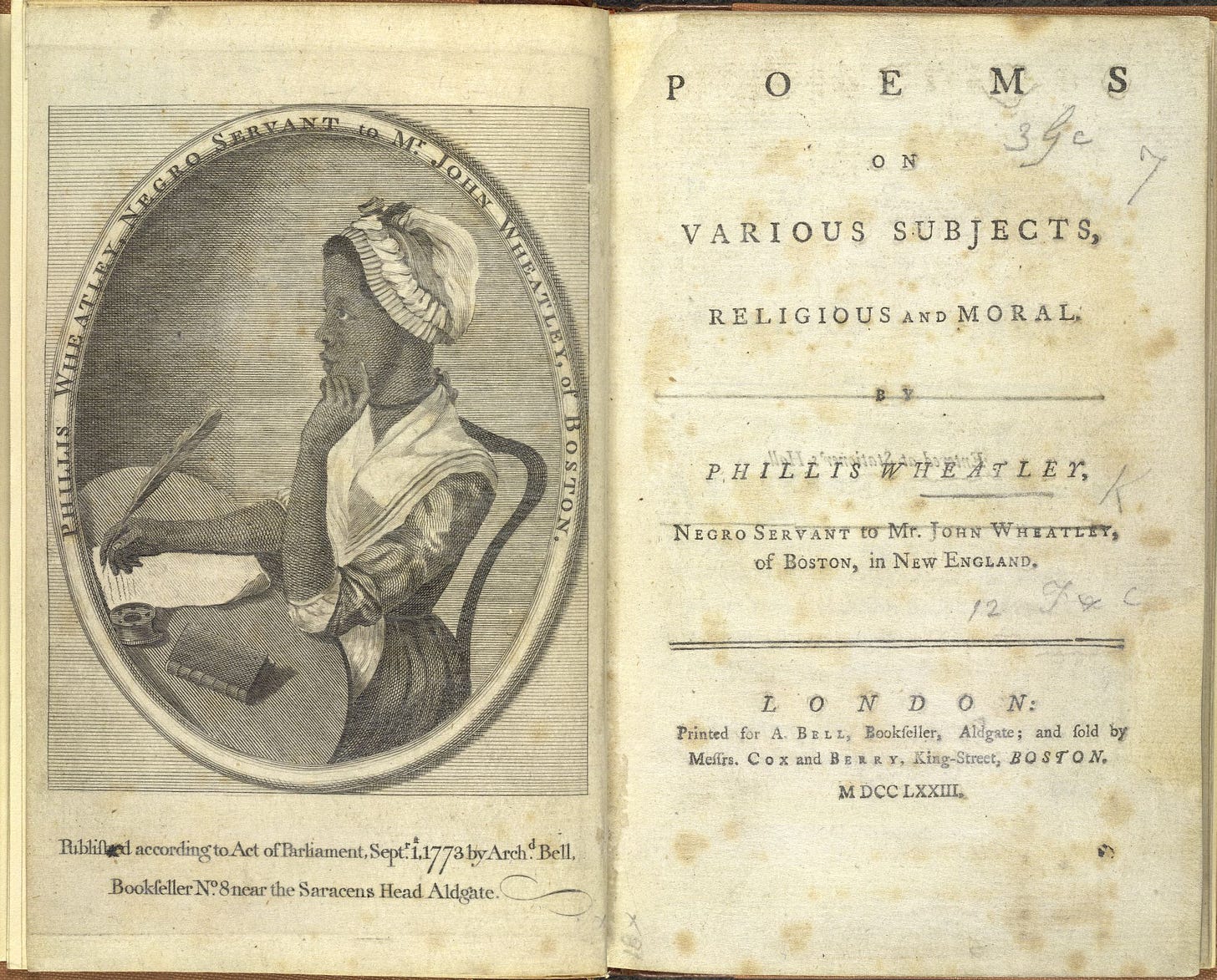

Black Americans not only participated in the general Revolutionary fervor but also pursued abolitionism, seeking the inclusion of freedom from slavery in the movement for freedom from British rule. In Phillis Wheatley’s book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, which appeared in 1773, on the eve of the Revolutionary War, in a poem dedicated “To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth,” she writes of “my love of Freedom,” recounts being kidnapped into slavery as a child in Africa, and asks the rhetorical question, “can I then but pray / Others may never feel tyrannic sway?” A year later, in 1774, Wheatley wrote in a letter to Samson Occom, a Native American Presbyterian minister, of the “Vindication of [the Negroes’] natural Rights.”

Wheatley thus extended to the condition of enslaved African Americans like herself the Revolutionary rhetoric of rights, liberty, and, in her reference to tyranny, arbitrary power. Note the subversive subtlety of her words, “I pray others may never feel tyrannic sway.” Addressed as it is to a British statesman, it is both a prayer that white colonists (“others”) may escape British tyranny as well as a prayer that “other” Africans may never have to experience American slavery.

Wheatley’s rhetoric and concerns are echoed in non-literary writing of the same period. For example, a 1773 petition written by enslaved people in Massachusetts asserts the language of rights: “Your Petitioners apprehend they have in comon with other men a naturel right to be free.”

The language of natural rights and of freedom employed by Wheatley and the anonymous petitioners, the petitioners’ reference to a common humanity, and Wheatley’s description of arbitrary power as “tyranny” illustrates a thesis of Albert Murray in The Omni-Americans (1970), a book about our “incontestably mulatto” (p. 23) national culture. He noted that although the first “Negroes” in North America were “slaves,” they were nonetheless “slaves who were living in the presence of more human freedom…than they or anybody else had ever seen before” and that “the conception of being a free man in America was infinitely richer than any notion of individuality in the Africa of that period.”10 This profound republican conception of freedom stirred not merely a desire in individuals to escape servitude but a desire to end slavery as an institution.9

3. Emancipatory consequences of the Revolution

The Revolutionary War and the promulgation of the Declaration of Independence only fanned the abolitionist flame that had been sparked in colonial America. Moved in part by a series of petitions and lawsuits initiated by free and enslaved black Americans agitating for freedom, the northern states would all abolish slavery in the decades immediately following the war.

We have seen how revolutionary language was employed by black and white abolitionists before 1776. After 1776, they will appeal to the language of the Declaration of Independence. Thus, on January 13, 1777, at a time when it was not clear what would be the outcome of the Revolutionary War, a free black man named Prince Hall (1735–1807), along with several others, petitioned the Massachusetts General Court for the abolition of slavery. The petition echoes the petition of 1773. It alludes to the war, that “present Glorious Struggle for Liberty,” and likens its own cause to that of the colonists, claiming to be composed “In imitation of the Lawdable Example of the Good People of these States.” It is replete with the language of equality and unalienable rights:

Your Petitioners Apprehend that Thay have in Common with all other men a Natural and Unaliable Right to that freedom which the Grat–Parent of the Unavese hath Bestowed equalley on all menkind….

The petition complains of the reduction of black people to “A state of Bondage and Subjection” and, professing a concern that “the Inhabitance of thes State” be “No longer chargeable with the inconsistancey of acting themselves the part which thay condem and oppose in Others,” rebukes “this Land of Liberty” for failing to apply to the cause of abolition the ideals that motivated her own independence:

Every Principle from which Amarica has Acted in the Cours Of their unhappy Deficultes with Great Briton Pleads Stronger than A thousand arguments in favowrs of Your petioners.

A petition two years later in New Hampshire, by twenty “natives of Africa,” pleads abolition “for the sake of justice, humanity, and the rights of mankind” and, echoing and extending the Declaration, professes that “the God of nature” granted black people “the most perfect equality with other men.”

Abolition and emancipation were also sought through lawsuits. In Massachusetts, slavery was effectively abolished by 1790. As David Hackett Fischer writes, “the prime movers” in this process “were individual slaves themselves.”11 Thus, in 1781 an enslaved man named Quock Walker (born 1753) sued for his freedom and won. In the same year, a brutally abused enslaved woman, Elizabeth “Mumbett” Freeman (1742–1829), heard the news that “all people were born free and equal,” and “resolved that she would try whether she did not come in among them.” She went to court and won her freedom. Thirty-nine years after her death, her grandson was born. His name was W. E. B. Du Bois. There were a total of six trials like those of Walker and Freeman in Massachusetts. By 1790 there were no slaves openly held as such in the state.12

The trials in Massachusetts were able to go forward and succeed because of the constitution written in 1780 by John Adams, a Founder who never enslaved his fellow human beings. The language of Article 1 of “Part the First” tracks closely that of the Declaration:

All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.

Quock Walker won his case when Chief Justice William Cushing of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts decided in his favor based on his interpretation of Adams’ constitution. The principle that “all men are born free and equal” entailed, for Cushing, that “perpetual servitude can no longer be tolerated in our government.” Mumbett Freeman conceived the idea to sue for freedom when she learned that the new constitution proclaimed that all were born free and equal.13

Massachusetts was not alone in alluding to the Declaration of Independence in its new constitution, and it was not alone, nor was it first, in abolishing slavery. The Revolution had turned the former colonies into the world headquarters of abolitionism.

The republic of Vermont’s constitution of 1777 was “the first written constitution in history to ban adult slavery.”14 The text of Chapter 1, Article 1 draws upon and extends the emancipatory language of the Declaration:

THAT all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable rights, amongst which are the enjoying and defending life and liberty; acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety. Therefore, no male person, born in this country, or brought from over sea, ought to be holden by law, to serve any person, as a servant, slave or apprentice, after he arrives to the age of twenty-one Years, nor female, in like manner, after she arrives to the age of eighteen years.…

Pennsylvania followed in 1780 with the “first gradual emancipation law in history.”15 Pennsylvania’s “Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” alludes to the Declaration in its wording about “the common Blessings” to which enslaved people “were by Nature entitled” and draws a parallel between the political slavery the colonists had suffered under “tyranny” and the chattel slavery suffered by black people. It also makes an anti-racialist appeal to God’s equal “Care and Protection” for the entire “human Species,” which includes “Men of Complexions different from ours and from each other.”

New Hampshire followed the lead of Massachusetts in 1783, the year the Revolutionary War ended. Connecticut and Rhode Island passed emancipation laws in 1784, New York in 1799, and New Jersey in 1804.

Sean Wilentz notes that by the time “the Federal Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, five northern states as well as the republic of Vermont...had either effectively banned slavery outright or passed gradual emancipation laws, commencing the largest emancipation of its kind to that point in modern history.”16 By 1804, black and white Americans, working together, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly, had abolished slavery or charted a course for its abolishment in seven of the original thirteen colonies (now states), the obvious holdouts being the six in the South.

It would take a Civil War half a century later to decide the issue for the entire country once and for all. Nevertheless, the Declaration continued to offer abolitionists their guiding principles. Frederick Douglass, in his searing 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” took America to task for the hypocrisy of its partial extension of freedom. Douglass did not derogate the Declaration but rather praised it, reprimanding the country for its failure thus far to live up to it, and urging white Americans to be true to their country’s stated ideals:

I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles.

Bernard Bailyn has asked how we should assess the fact that although abolitionism exploded in the years before and especially immediately after the Revolution, America did not, as a nation, abolish slavery. He writes—

Everywhere in America the principle prevailed that in a free community the purpose of institutions is to liberate men, not to confine them, and to give them the substance and the spirit to stand firm before the forces that would restrict them. To see in the Founders’ failure to destroy chattel slavery the opposite belief, or some self-delusive hypocrisy that somehow condemns as false the liberal character of the Revolution—to see in the Declaration of Independence a statement of principles that was meant to apply only to whites and that was ignored even by its author in its application to slavery, and to believe that the purpose of the Constitution was to sustain aristocracy and perpetuate black bondage—is, I believe, to fundamentally misread the history of the time.

[…]

Only gradually were men coming to see that [chattel slavery] was a peculiarly degrading and a uniquely brutalizing institution, and to this dawning awareness the Revolution made a major contribution. To note only that certain leaders of the Revolution continued to enjoy the profits of so savage an institution and in their reforms failed to obliterate it inverts the proportions of the story. What is significant in the historical context of the time is not that the liberty-loving Revolutionaries allowed slavery to survive, but that they—even those who profited directly from the institution—went so far in condemning it, confining it, and setting in motion the forces that would ultimately destroy it.17

And destroy slavery the forces set in motion by the Revolution ultimately did. The story of slavery’s destruction is, in the end, a transatlantic story, involving, among others, Britain, France, and Haiti, the site of history’s first successful slave revolt. Many of these countries succeeded in abolishing either the transatlantic slave trade, or slavery within their borders, or both, before the United States did. Denmark, for example, was the first European country to ban the slave trade, in 1792. Significantly, the report of the commission that led to the ban cites as inspiration American abolitionists Anthony Benezet and John Woolman and their successful efforts in America.18 (Britain and America both banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1807.) Yet the epicenter and inspiration for all this abolitionism was America and her Revolution. As Christopher Leslie Brown writes in Moral Capital,

More than a decade before the development of abolitionism in Britain, the middle and northern colonies in North America presented the unusual spectacle of societies with slaves turning against the practice of human bondage.19

Britain’s abolitionist movement would coalesce, according to John Oldfield,

in the years immediately following the American Revolution (1776–1783). It is no coincidence, for instance, that the first organised anti-slavery society in Britain, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST), was founded in May 1787, taking its inspiration from events on the other side of the Atlantic, where the American Revolution had witnessed the first tentative steps to abolish slavery and the slave trade.

In the largest sense, as Jonathan Israel writes, the American Revolution changed the world in profound ways, “commenc[ing] the demolition of the early modern hierarchical world of kings, aristocracy, serfdom, slavery, and the mercantilist colonial empires, initiating its slow, complex refashioning into the basic format of modernity.” It did so by “laying the path by which the modern world stumbled more generally toward republicanism, human rights, equality, and democracy.”20

4. Revolutionary Ideals as Slavery’s Solvent

The Revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality were like a solvent that would, unless they were abandoned, eventually dissolve slavery in America. The choice that America faced was either to discard its ideals or to discard slavery.

On December 20, 1860, following Lincoln’s election, six slaveholding states voted for secession. Texas joined them on February 1, 1861. Lincoln delivered a speech three weeks later, on February 22, 1861, at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where the Declaration had been signed. He appealed to

that sentiment in the Declaration of Independence which gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but, I hope, to the world, for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weight would be lifted from the shoulders of all men. This is the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence.

Lincoln’s reference to slavery is clear.

The Secessionists saw America’s founding in a similar light. This is starkly evident in the “Cornerstone speech” of Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens, delivered one month after Lincoln’s speech at Independence Hall. Stephens branded Southern secession as a new “revolution.” He admitted that “the proper status of the Negro in our form of civilization” was “the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.” And he said of “our new government,” the Confederacy, that

its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests upon the great truth that the Negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

He noted that the Declaration’s principal author, Thomas Jefferson, “had anticipated” the status of black Americans “as the ‘rock upon which the old Union would split.’ He was right.” Stephens further noted that Jefferson “and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution” believed—

that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away.

Stephens proposed, then, that his slaveholders’ revolution had resulted in the formation of a “new constitution” that “has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us.”

As it happens, Frederick Douglass understood the principles of America’s founding much as Stephens did. In a speech delivered almost exactly one year before Stephens’ speech, Douglass asked,

Does the United States Constitution guarantee to any class or description of people in that country the right to enslave, or hold as property, any other class or description of people in that country?

He answered his own question thus: “I deny that the Constitution guarantees the right to hold property in man.” Eight years earlier, he had declared, “the Constitution is a glorious liberty document.”

Douglass and Stephens alike believed that the principles of the Revolution, the “saving principles” of the Declaration and the Constitution’s refusal to grant a “right to hold property in man,” had led to the creation of a political community that could not abide slavery forever. Hence Stephens’ assertion of slaveholders’ need to secede and establish a new constitution founded on white superiority and black servitude, just the sort of inequality, unliberty, and tyrannical domination rejected, at least aspirationally, by the Founders. Hence, too, Douglass’ contrary insistence that he “would act for the abolition of slavery through the Government—not over its ruins.” Stephens’ Confederate revolution and Douglass’ Constitutional conservatism only make sense in light of the thesis that America’s Revolutionary ideals are solvents inexorably destined to wash away racial inequality and slavery.

5. Achieving Our Country

Samuel Johnson’s famous quip, “How is it we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?,” derives its bite from the fact that American colonists were in fact uniquely obsessed with liberty. Calling out hypocrisy is worthwhile. But would we prefer that the Founders had not been hypocrites and had instead devised, like Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, rationalizations for slavery and embedded them in our founding documents? While we may regret that the Founders did not act as we fancy that we, with the benefit of hindsight and nothing at stake but a pretension to virtue, would act, we should nonetheless celebrate the fact that they “set in motion the forces that would ultimately destroy” slavery, as Bailyn noted.

George Packer cites the philosopher Richard Rorty, who wrote in Achieving Our Country (the title an allusion to James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time) that national narratives are “attempts to forge a moral identity.” The debate over which narratives to accept and which to reject amounts, Rorty argued, to “an argument about which hopes to allow ourselves and which to forgo.”21

On this Fourth of July, we must not let a progress-free progressivism persuade us to forgo the hope that in the future, as in the past, we can take possession of those ideals of liberty and equality that are our heritage—ideals which black and white Americans together elaborated in writings and institutionalized in law, ideals by which they repudiated oppression and effected emancipations and abolitions—and join in the ongoing work of achieving our country together.

In addition to the references cited in the footnotes below, see the following:

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Emancipation (New York: Knopf, 2014).

Barbara J. Fields, “Slavery, race and ideology in the United States of America,” New Left Review, 181 (1990): 95–118 .

James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2012).

Paul J. Polgar, Standard-Bearers of Equality: America’s First Abolitionist Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

Benjamin Arthur Quarles, The Negro in the Civil War (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1953).

Benjamin Arthur Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1961).

Benjamin Arthur Quarles, Black Abolitionists (Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 1969).

Manisha Sinha, The Slaves Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

Gordon Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.)

1 Benjamin Quarles, “Foreword,” in Am I Not a Man and a Brother: The Anti-Slavery Crusade of Revolutionary America, 1688–1788, ed. Roger Bruns (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1977), xiii–xiv.

2 “Organized antislavery politics originated in America”: Sean Wilentz, No Property In Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the American Founding (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2018), 25.

3 David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966), 489.

4 Danielle Allen, Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality (New York: Liveright, 2014).

5 Bernard Bailyn, “Central Themes of the American Revolution: An Interpretation,” in Essays on the American Revolution, eds. Stephen G. Kurtz and James H. Hutson (New York: Norton, 1973), 12, 27.

6 Bailyn, “Central Themes,” 26.

7 Roger Bruns (ed.), Am I Not a Man and a Brother: The Anti-Slavery Crusade of Revolutionary America, 1688–1788 (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1977), 104.

8 Bruns (ed.), Am I Not a Man and a Brother, 112.

9 Sidney Kaplan and Emma Nogrady Kaplan, The black presence in the era of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press, 1989), 12.

10 Albert Murray, The Omni-Americans: Some Alternatives to the Folklore of White Supremacy (New York: Library of America, 1970/2020), 19 (emphasis in the original).

11 David Hackett Fischer, African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022), 82.

12 Details and quotations from Hackett Fischer, African Founders, 82–85.

13 Hackett Fischer, African Founders, 83.

14 Wilentz, No Property In Man, 31

15 Wilentz, No Property In Man, 31.

16 Wilentz, No Property In Man, 25.

17 Bailyn, “Central Themes,” 28–29.

18 Erik Gøbel, The Danish Slave Trade and Its Abolition (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 105. The Danish Slave Trade Commission’s Report states that the most successful efforts to date to ban the slave trade and abolish slavery had been carried out in several American states, under the leadership of Quakers like Woolman and Benezet (p. 191).

19 Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 106. Those reluctant to accept America’s leadership on abolitionism tend to point to the British case of Somerset vs. Stewart (1772) as evidence of British superiority in this domain. However, as Brown points out, Somerset “preserved the slaveholders’ right to the service of their slaves but not the right to enforce it. The decision left the legality of slavery in England as ill defined as before” (p. 97). Brown describes measures like Somerset thus: “these attempts to expel slavery from a particular community arose from doubts about the benefits of slavery while accepting that elsewhere, among others, the institution would continue” (p. 79).

20 Jonathan Israel, The Expanding Blaze: How the American Revolution Ignited the World, 1775–1848 (Princeton University Press, 2017), 2, 24.

21 Richard Rorty, Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998), 13–14.

'While we may regret that the Founders did not act as we fancy that we, with the benefit of hindsight and nothing at stake but a pretension to virtue, would act, we should nonetheless celebrate the fact that they “set in motion the forces that would ultimately destroy” slavery, as Bailyn noted.'

Presentism is one of the most virulent intellectual diseases of our time. Your essay is a vaccine to this illness of mind.

Jackson and Rao and many others have presented me with theses that have prompted the finest antitheses - yours being a superlative example. Thus history progresses. Every day's a classroom day. As Goya said in rheumy old age 'Aún aprendo'.