American literature

BIGGER’S DREAM: KILLING AND SELF-PRESERVATION

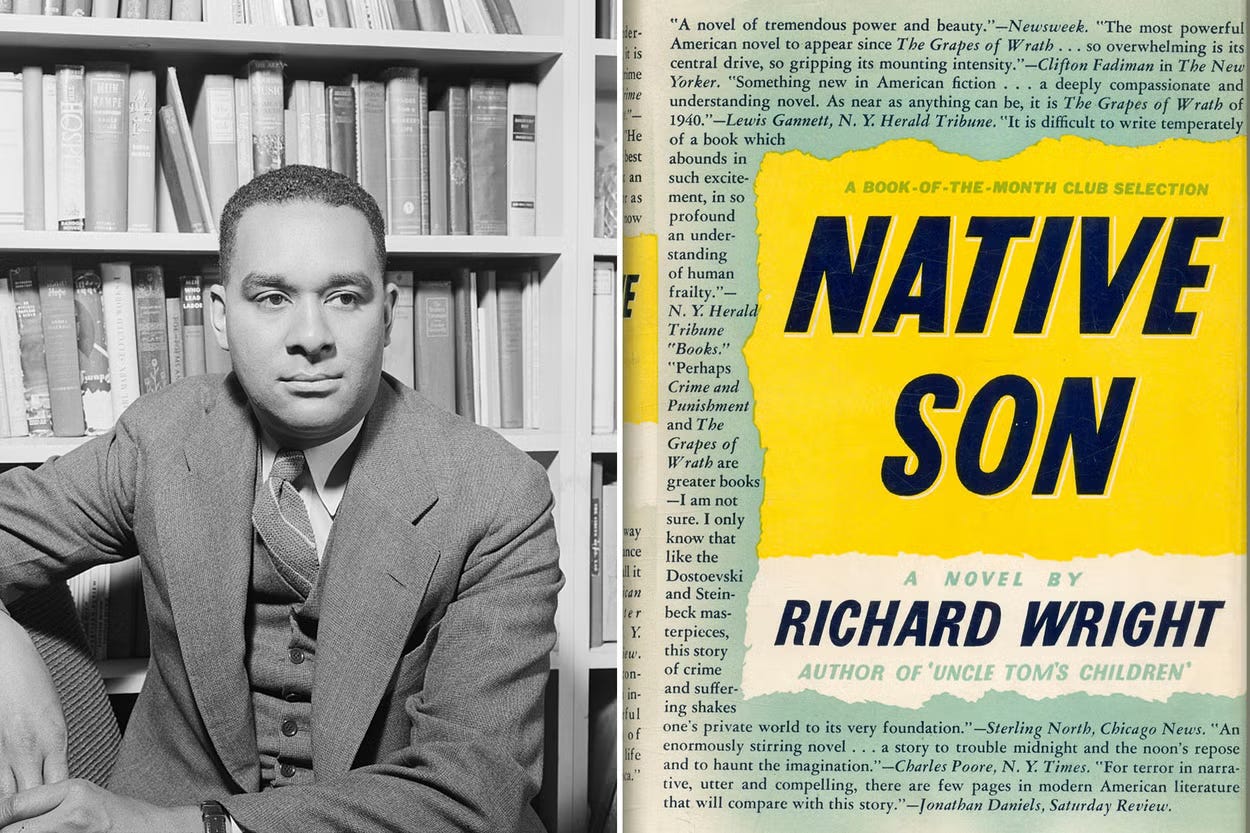

An analysis of Richard Wright's Native Son

Maximilian Werner

Editors’ note: This is the second of two essays on African-American literature by Maximilian Werner that we are publishing in JFBT. The first essay, on Countee Cullen’s 1925 poem, “To John Keats, Poet. At Springtime,” appeared on January 20.

Among readers of Richard Wright’s 1940 novel Native Son there has without doubt been some disagreement as to whether or not the poor, young, angry black main character, Bigger Thomas, actually meant to kill Mary, the progressive white woman who sees Bigger as symbolic of a “cause” and tries to befriend him. However, when we consider how Bigger changes once he has killed Mary, we begin to see that a more revealing question to ask would be what killing Mary meant for him. Wright provides us with a useful tool when, in reference to the slaying, he writes, “[Bigger] felt that he had been dreaming of something like this for a long time, and then, suddenly, it was true” (p. 88). Thus, Bigger's dream recalls Genesis 2:21-22, when “the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he slept: and he took one of his ribs[and] made he a woman.” Both Bigger and Adam, then, awoke to find their dreams realized. This being the case, strong parallels are not only created between Bigger and Adam, but between Mary and Eve as well.

For Adam and Bigger, the introduction of Eve and Mary “meant death before death came” (p. 228) and, ultimately, the fall. When God asked Adam why he ate from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, he replied, “The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I did eat” (Gen. 3:13). The transference of blame, however, is not quite as subtle for Bigger: “She made me do it! I couldn’t help it! She should have known better” (p. 108).1 Thus, partaking of the fruit brought Adam knowledge and self-awareness, while committing murder brought Bigger knowledge as well. Both acts were extreme norm violations, and in both cases, “the eyes of them both were opened” (Gen. 3:7) as a result. When Bigger murdered Mary, just as when Adam had eaten, “he had created a new world for himself, and for that he was to die” (p.264), just as Adam and Eve were cursed by God to die for their transgression.

As we might expect, with Bigger’s new world came a new understanding. “[T]hings were becoming very clear” (p. 102), and “he saw it all very sharply and simply” (p. 108). Here, we are again reminded of Adam when Wright writes, “Like a man reborn, [Bigger] wanted to test and taste each thing now to see how it went; like a man risen up from a long illness, he felt deep and wayward whims” (p. 106). Bigger’s perception of everything, whether it be his mother or friends, his little sister Vera or his little brother Buddy, had changed. “He could see it in the very way Vera moved her hand when she carried the fork to her mouth; she seemed to be shrinking from life in every gesture she made” (p. 104). After the murder, Bigger began to see and feel things for the first time: thus “it was the first time he had been in [his friends’] presence without feeling fearful” (p. 107), and “for the first time in his life he moved consciously between two sharply defined poles” (p. 141). “Never in all his life, with this black skin of his, had the two worlds, thought and feeling, will and mind, aspiration and satisfaction, been together; never had he felt a sense of wholeness” (p.225). Like Adam, he has attained knowledge.

It is important to remember that “under and above it all there was the fear of death before which [both Bigger and Adam were] naked and without defense” (p.256). It would, however, be inaccurate to say that Bigger had always felt defenseless against death. Because it is not until the end of the book that he realizes “he had reached out and killed and had not solved anything” (p. 255), we may assume that of the many ways Bigger “blotted” things out, and thus protected himself, killing was one. For “the thought of what he had done [to Mary], the awful horror of it, the daring associated with such actions, formed for him for the first time in his fear-ridden life a barrier of protection between him and a world he feared” (p. 101).

What Wright calls a “barrier of protection,” Freud, according to Ernest Becker, calls the “death instinct” (98), which represents, to modify a quotation from Becker, “[Bigger’s] desire to die, but [he] can save [himself] from [his] own impulsion toward death by redirecting it outward. The desire to die, then, is replaced by the desire to kill, and [Bigger] defeats his own death instinct by killing others” (ibid.) It is thus that Bigger “buys himself free from the penalty of dying, of being killed” (ibid., p. 99), at least symbolically.

Bigger’s words support this theory when he notes, “Rape was what one felt when one’s back was against a wall and one had to strike out, whether one wanted to or not, to keep the pack from killing one” (p. 214). Similarly, when Bigger realized that his girlfriend Bessie could not be taken or left behind, and therefore resolved to kill her, “it was not with anger or regret that he thought this, but as a man seeing what he must do to save himself” (p. 216). After all, “It was his life against hers” (p. 222). Accordingly, he rapes her and then kills her. Thus, killing for Bigger meant both the knowledge and the emancipation of what he was, i.e., one among oppressed millions. “Never had he had the chance to live out the consequences of his actions; never had his will been so free as in this night and day of fear and murder and flight” (p. 225). Adam and Eve’s wills are free, too, as they live out the consequences of their actions, leaving Eden at God’s command, to begin a life of toil, suffering, and ultimately death.

Works Cited:

Wright, Richard. Native Son. Harper & Brothers, 1940.

Becker, Ernest. The Denial of Death. 1st paperback edition. New York, Free Press, 1975.

The Bible. New International Version, Zondervan, 2011.

[1] In Genesis, Eve literally knew better than Adam insofar as she ate the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil before offering it to him.

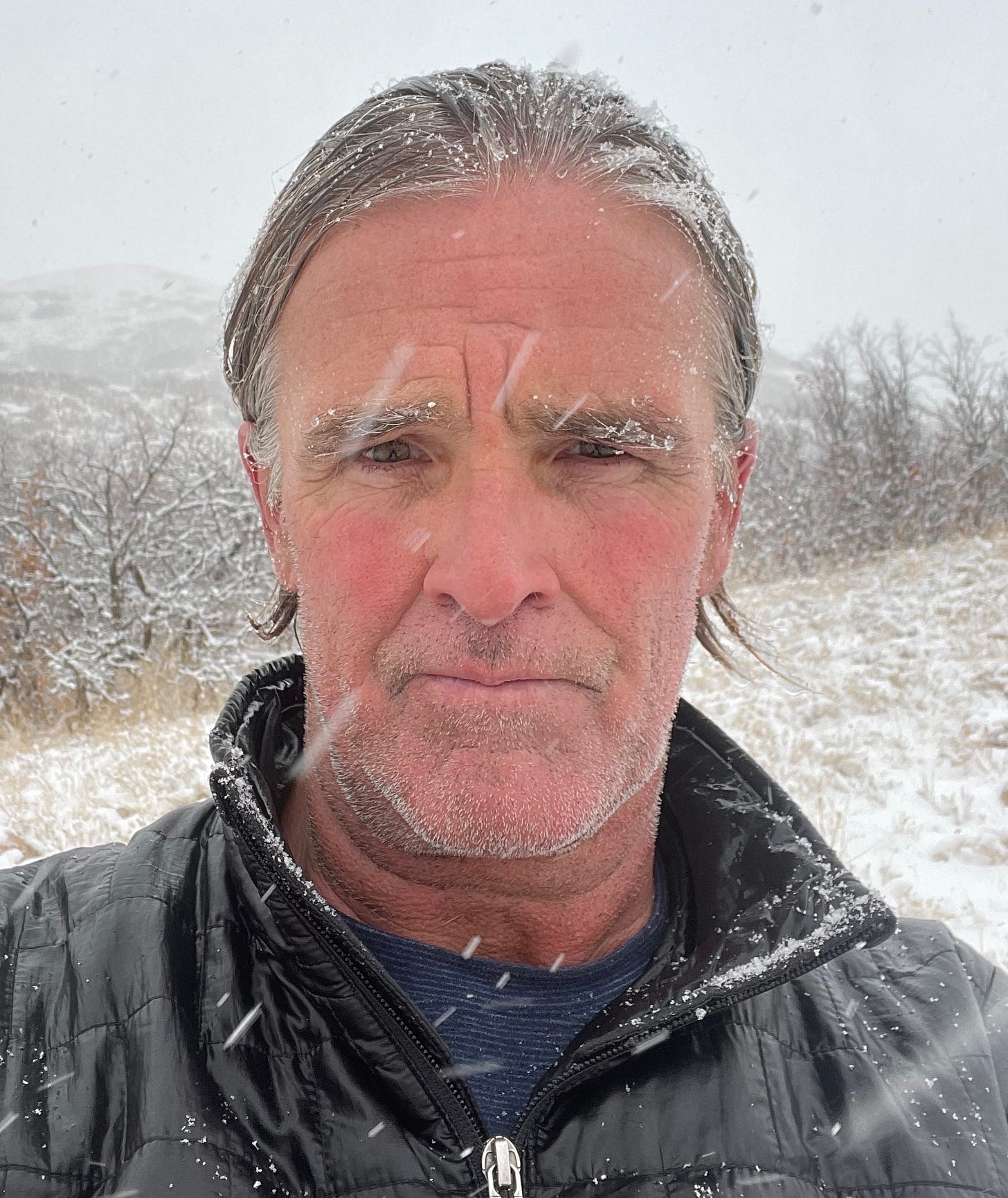

Maximilian Werner is an accomplished author and Professor in the Department of Writing and Rhetoric Studies at the University of Utah. With over two decades of teaching experience, he specializes in courses such as Intermediate Writing, Environmental Writing, and Writing about War.

Werner holds an MFA from Arizona State University and has published seven books. His works include the novel Crooked Creek, the memoir Gravity Hill, and the essay collections Black River Dreams and The Bone Pile: Essays on Nature and Culture. His poetry collection, Cold Blessings, and his nonfiction work, Wolves, Grizzlies, and Greenhorns: Death and Coexistence in the American West, further showcase his diverse literary talent.

His writing often explores themes of nature, culture, and the human experience, particularly in the context of the American West. Werner’s creative and scholarly work has been featured in numerous journals and magazines, including The Robert Frost Review, The Ecological Citizen, Times Higher Education, The Emerson Society Papers, Inside Higher Education, Counterpunch, and The North American Review.

In addition to his literary achievements, Werner is recognized for his contributions to environmental and cultural discourse, making him a respected voice in both academic and literary communities.

In Genesis, Eve literally knew better than Adam insofar as she ate the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil before offering it to him.

Interesting. Thanks for posting. Might be worth exploring Native Son in relation to the storyh of Cain and Abel, and even more worth considering in relation to Moses, the freedman among the enslaved Jews, and the Egyptian he murdered.