ABRIDGED: Six Unsettling Features of DEI in K-12

A briefer version of our guide for parents, educators, and anyone concerned about new curricular interventions

Education

ABRIDGED: SIX UNSETTLING FEATURES OF DEI IN K-12

A briefer version of our guide for parents, educators, and anyone concerned about new curricular interventions

The Editors

Editor’s note: By popular demand, we offer this is a brief, abridged version of the third article in a series of “Back to School” pieces on education that we published this fall. Read the original post as well as the first, second, and fourth posts in the series.

The purpose of this article and its associated downloadable Powerpoint is to make available, for parents, educators, and all who care about K-12 education, information about some of the potentially harmful ideas and practices around race that have become increasingly prevalent in K-12 education. For convenience, we call these new ideas and practices “DEI,” that is, “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.” Other terms you may have seen for roughly the same phenomenon include “Critical Race Theory (CRT),” “(critical) social justice,” “diversity work,” and “antiracism.”

In the following six sections, we explore six unsettling features of DEI as it manifests in K-12. A final coda offers some alternatives to traditional DEI that are worth exploring. We hope that you find this post to be a useful resource. You may click on a section number to jump to that section:

1. "Oppressed vs. oppressor" framing

2. "White supremacy culture" framing

3. Segregating children by race or ethnicity in “affinity groups”

4. Constructive vs. Critical/Liberated Ethnic Studies

5. Lowering/eliminating standards in math education

All six of these features of DEI may have unintended negative effects on children. They may mislead students (and educators as well) about basic facts about American society and they may damage children’s psychological health, sense of self, and sense of agency. We regard these six practices as potentially harmful to all students, regardless of race. However, because of the way DEI insists on racializing students and because of the way that it crudely essentializes different racial identities, it poses distinct and different dangers to white students and to students of color. As we explain below, DEI tends to demonize white children even as it promotes in black children feelings of victimhood, disempowerment, and alienation from white peers and teachers and from their country.

None of this is to say that DEI is intended to be harmful. Nor is it to say that every school that adopts a DEI program is guaranteed to do harm to students. It is merely to say that some features of DEI have the potential to do harm. We offer the following essay and associated Powerpoint in an effort to help parents and other concerned parties identify worrying DEI ideas and practices and discuss them fruitfully with school administrators, teachers, and others charged with their children’s education.

1. “Oppressed vs. oppressor” framing

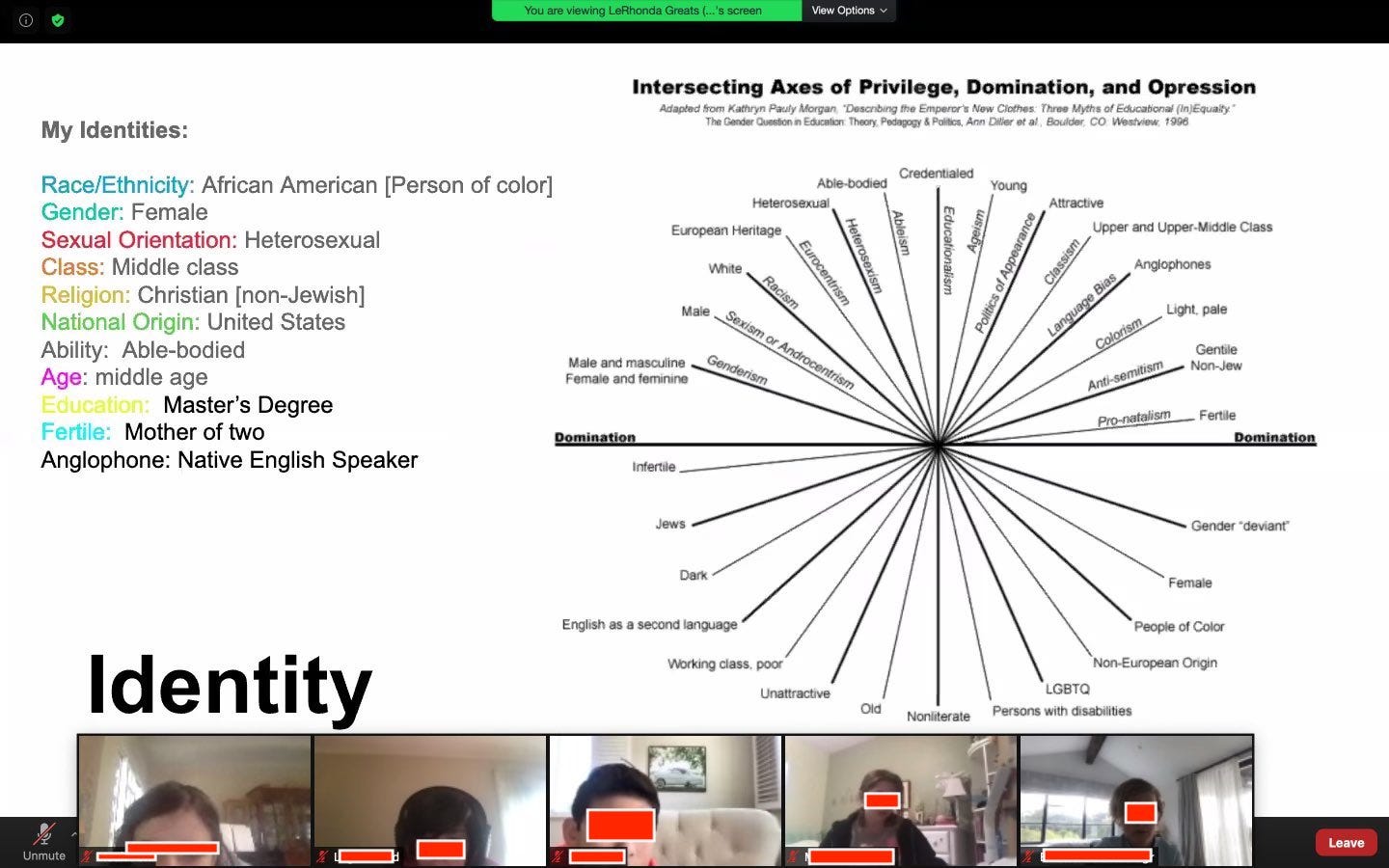

A commonly employed DEI framework for understanding American society and personal identity is the “oppressed vs. oppressor” dichotomy. In this paradigm, students are taught to divide people into one of two categories: they are either “oppressed” (or “resistors”) or they are “oppressors” (or more often bearers of “privilege” or agents of “domination”). See figures 1 and 2.

Those who have “privilege” or who sit at the top of the “domination” hierarchy are, according to figures 1 and 2, white, male, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied, healthy, literate, and so forth. Those at the bottom of the “domination” hierarchy, who must meet “oppression” with “resistance,” are dark-skinned, female, transgender, LGBTQ, disabled, illiterate, and so on.

The thesis that being white confers privilege or that it involves domination of others can devolve into condemnation of an essentialized “whiteness” as such, as in the case of Anastasia Higginbotham’s 2018 children’s book, Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness (Figure 3). The book teaches children that they can “sign” a “contract” with “whiteness,” which is represented by a collage image of the devil. “White” children get “stolen land, stolen riches, and special favors.” In return, “whiteness” gets “to mess endlessly with the lives of your friends, neighbors, loved ones, and all fellow humans of COLOR” as well as “your soul.”

How could teaching children to view their “identities” in these ways go wrong? Here are a few ways it could go wrong for white children. We’ll see how it could go wrong for black and so-called “mixed” children momentarily.

● Framing whiteness (and being male, heterosexual, etc.) as oppressive and privileged merely substitutes one hierarchy for another, in which being NOT white (and NOT male, NOT heterosexual, etc.) is morally “better.”

● Framing “whiteness” as oppressive can quite literally demonize white students, as the devil depicted in Higginbotham’s Not My Idea suggests. Indeed, Paul Rossi, formerly a math teacher at Grace Church School in New York City, prompted the head of school, George Davison, to admit as much in a recorded phone call:

Davison: “We're demonizing ki… We're demonizing white people, for being born.”

Rossi: “And are some of our students white people?”

Davison: “Yes.”

Rossi: “Okay, so we're demonizing white kids. Why don't you just say it?”

Davison: “We are using language that makes them feel less than, for nothing that they are personally responsible for.”

● Given this new, adult-sponsored hierarchy of oppressed vs. oppressor, some children may strive to disassociate themselves from the “bad,” “demonized” side, i.e., from being white, heterosexual, and so on, and find ways—any way—to construct an “immutable identity” for themselves on the “good” side, the “oppressed,” “dominated,” “resisting” side.

Indeed, something of this sort may now be happening. The number of teenagers identifying as “trans” has increased dramatically over the last five years. More strikingly, there is a swiftly growing cohort of young people who identify as LGBTQ but engage in only heterosexual behavior—and are politically left-leaning, a sign that they may be more receptive to the oppressor vs. oppressed framing. There is, of course, absolutely nothing wrong with being LGBTQ. The swift and sudden rise in such identifications may be a result of other cause(s), such as the recent, precipitous and wholly welcome destigmatization of LGBTQ (which itself might call into question the DEI narrative that LGBTQ is a deeply oppressed category). Nonetheless, it is possible that recent trends are at least partly the result of a desire to stake out morally good “oppressed” identities on the part of children who have internalized DEI messaging.

● Alternatively—and this is terrifying—some white students might embrace the privilege they’ve been told they have. If we tell white children that they benefit from being white, or if we communicate to them, even indirectly, that they are superior to others, might not some of them respond by feeling not so much chastened but rather emboldened to embrace their “whiteness,” with all its superiority and privilege?

What can we do, in the face of these concerns? Perhaps we serve children better if we do not label and divide them according to the terms of a new moral hierarchy, even in the name of “dismantling” previous or existing hierarchies. Presumably, we all want our children to relate to one another as peers and equals, rather than as bearers of “privileges” at the expense of other classmates or as victims of “oppression” due to other classmates’ unearned advantages. Instead of teaching any child that merely being white is in some way bad or suspect, we should teach all children about the unbounded possibilities for cooperation, mutual respect, and love across lines of perceived difference.

The oppressor vs. oppressed framing can, unsurprisingly, present problems for black and “mixed” children, as well. Consider the case of William Clark, the “mixed” son of a black mother, Gabrielle Clark. In his senior year at Democracy Prep charter school in Las Vegas, he took a class in which he was asked to “label and identify” the various aspects of his “identity.” He was then asked to assess whether each aspect of his identity had “privilege or oppression attached to it” (see Figure 4).

William refused to submit to what is arguably unconstitutional compelled speech. The school failed him in the class, thereby threatening his graduation. His mother sued. Eventually, William was allowed to opt out of the class and graduate, but the school did not give in without a legal fight that cost Gabrielle Clark tens of thousands of dollars.

Sometimes the oppressed vs. oppressor dynamic is both racialized and gendered. In these cases, the presumption in DEI ideology is that the intersection (hence the CRT term “intersectionality”) of an oppressed racial identity with an oppressed gender identity has oppressive interaction effects that add up to more than the sum of the parts.

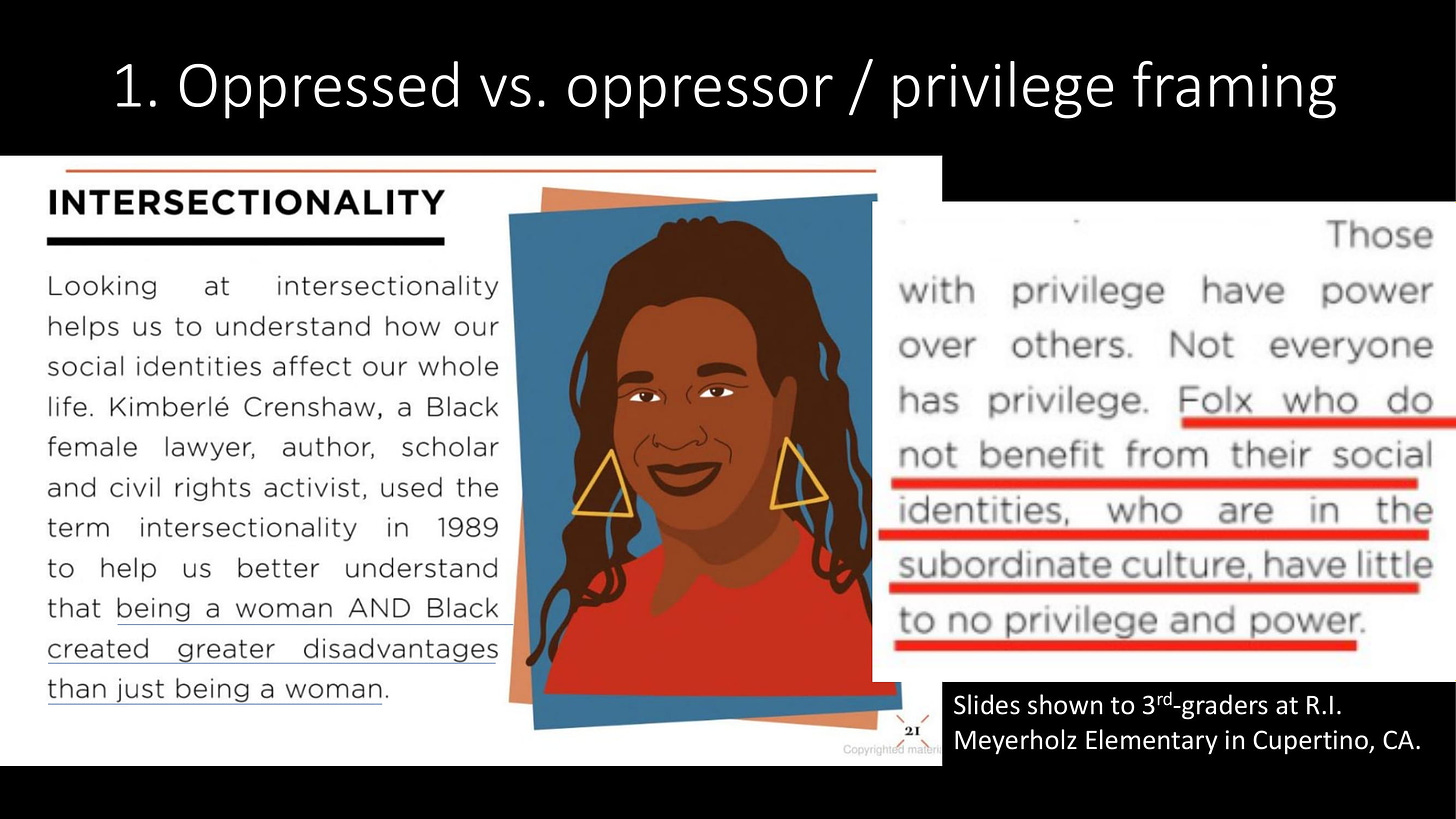

An example of intersectionality in K-12 comes from a lesson taught to third-graders at R. I. Meyerholz Elementary School in Cupertino, California. The eight-year-old children were shown a slide explaining that “being a woman AND Black created greater disadvantages than just being a woman.” Another slide drove the larger point of the lesson home: “Folx who do not benefit from their social identities, who are in the subordinate culture, have little to no privilege and power” (see Figure 5).

The fundamental point we wish to make here is that a two-dimensional “intersectional” approach—in which some “identities,” regardless of geography, family income and wealth, family educational attainment, and so on, are disadvantageous—is reductive and may be disempowering to black girls (recall that this was taught to eight-year-old children). Being a black a woman does not, as a matter of fact, inevitably result in “greater disadvantages” and “little to no privilege and power.” Why would we want schools teaching our young black daughters that it does?

The “oppressed vs. oppressor” framing has the potential to damage not only black girls but black boys as well. If we send a generalized message to young children to the effect that “Folx who do not benefit from their social identities…have little to no privilege and power,” then we risk destroying black children’s sense of agency and self-determination.

This is what happened to a black boy in Evanston, Illinois, when a “Black Lives Matter at School” curriculum was introduced in his school. His mother, Ndona Muboyayi grew up in Evanston and is a member of the local NAACP. As an adult, she moved to Toronto, married a Congolese man, had children, and moved her family back to Evanston. In her telling, when her children began attending Evanston schools, “within the first year, my children were being taught about white supremacy and white privilege and that all white people were rich and racist.”

The lesson sank in. Her son returned from school and announced that he could not pursue his dreams of becoming a lawyer, because, in his words, “there are these systems put in place that prevent Black people from accomplishing anything” (Figure 6). Whatever inequities do remain in American life, no parent wants their son to learn at school that he cannot pursue his dreams because of his skin color.

In general, under a DEI regime, white children may be demonized for their “whiteness” while black children may be disempowered by messages about the pervasive oppression they must labor under.

The oppressed vs. oppressor framing not only demonizes and disempowers, but also pathologizes black life, conveying to all students the destructive message that black people are all poor, oppressed victims worthy of pity. Black Americans are not all poor and oppressed. To imply that they all are may lead black children to despair of their prospects in life. This would be tragic. And feelings of pity, on the part of non-black people, for an entire caste of supposedly oppressed victims is, ultimately, not a path to solving the problems that do exist. The fact is, black people have made tremendous gains in the last 50-70 years and there is a firm factual basis for communicating to children an empowering message of agency and optimism.

2. “White Supremacy Culture” framing

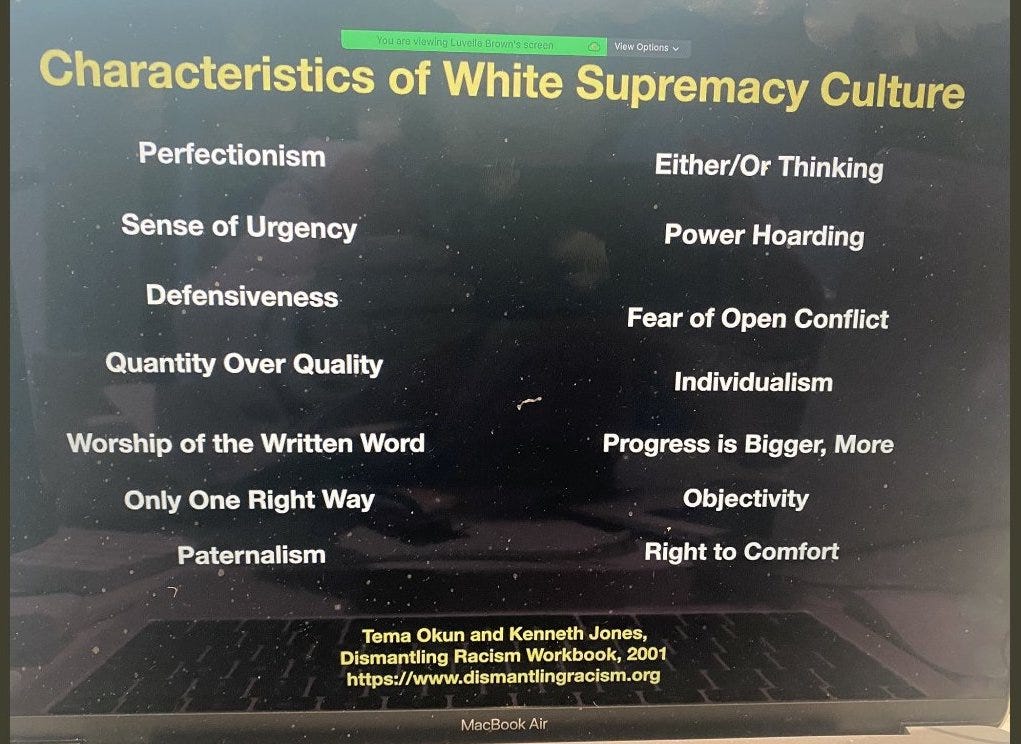

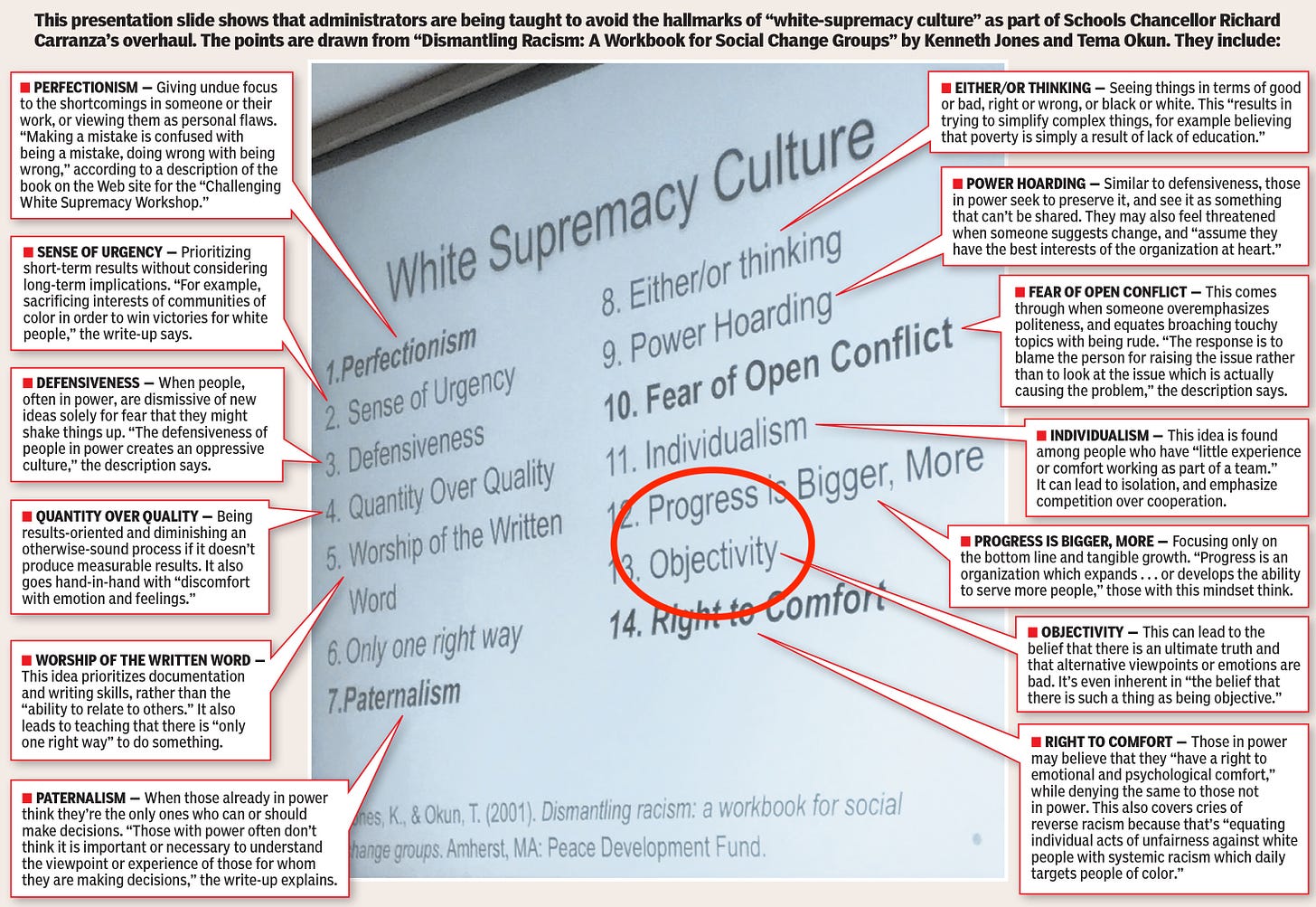

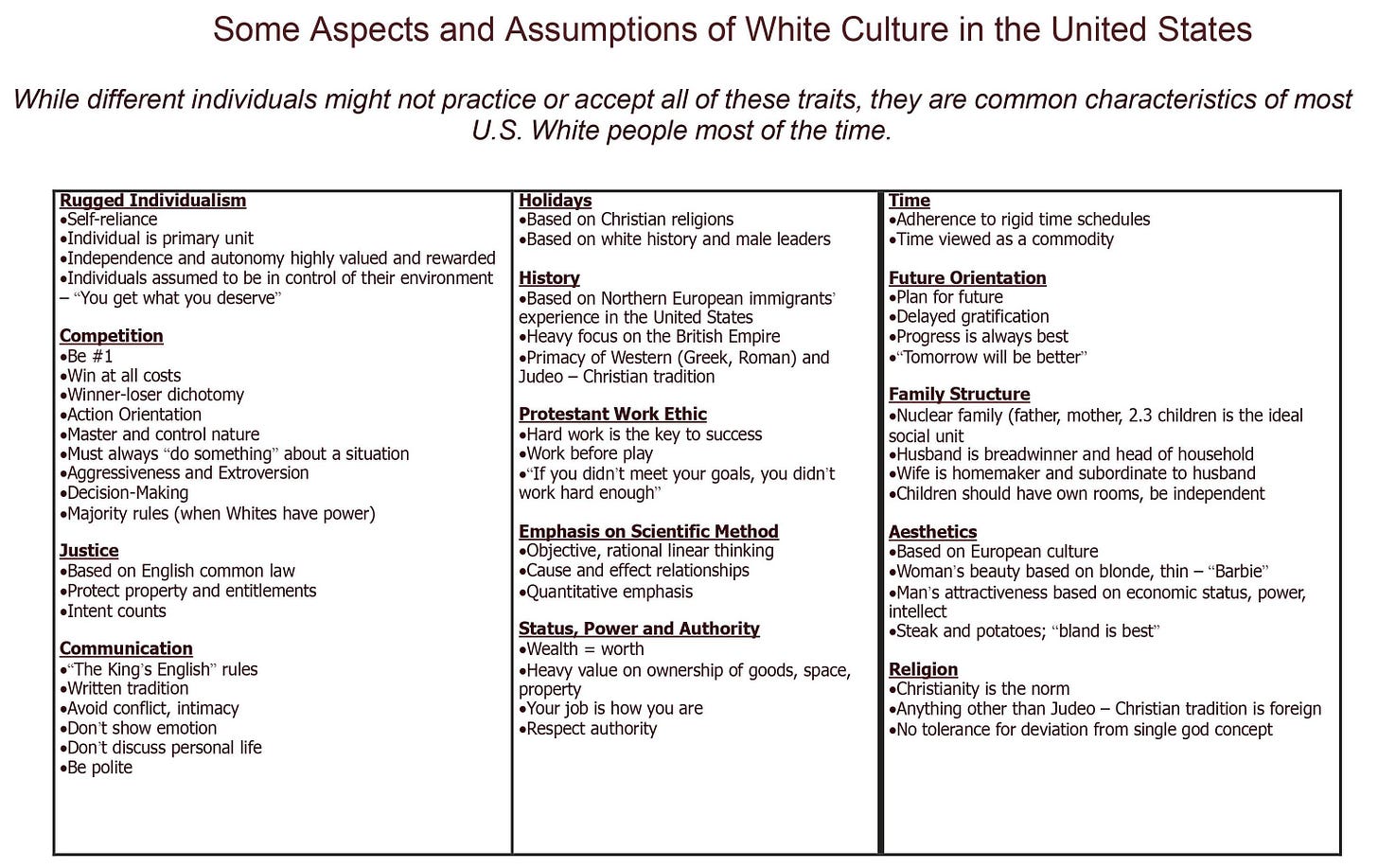

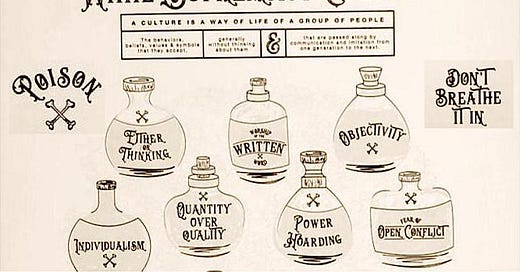

Another framing commonly encountered in DEI curricula is that of “white supremacy culture.” This concept is primarily associated with two names, Tema Okun and Judith Katz. The hallmark of the white supremacy culture thesis is that many of the traits and supposed virtues valued in American society, such as “objectivity,” “rational, linear thinking,” “worship of the written word,” and “planning for the future” are distinctively and uniquely “white” cultural constructs.

The idea is twofold: first, that these values are wielded like weapons by the white majority to ensure and perpetuate their domination, and second, that when “white” institutions such as schools compel black people to assimilate to these values in order to succeed, it is a form of oppression. Figures 7 and 8 present two slides based on Tema Okun’s work that were shown to teachers and administrators, the first by Luvelle Brown, the Superintendent of the Ithaca City NY School District, and the second by Richard Carranza, NYC Schools Chancellor under Mayor de Blasio.

The journalist Matt Yglesias notes that Tema Okun’s work is remarkably widespread and also “really dumb.” He notes that most of the things that bother Okun, like “either/or thinking,” “defensiveness,” and “only one right way,” have absolutely nothing “to do with race or white supremacy.” Anyone, anywhere can manifest them.

Judith Katz’s list of “white” traits (Figure 9) is much more detailed than Okun’s. It includes such qualities as “self-reliance,” the conviction that “intent counts,” the imperative to “be polite,” the belief that “hard work is the key to success,” a penchant for “objective, rational linear thinking,” the ability to “delay gratification,” and the foresight to “plan for the future.” It is also less widely referenced, although it did make a dramatic appearance in an embarrassing chart, since removed, on “Aspects and Assumptions of Whiteness and White Culture in the United States,” displayed by the National Museum of African American History and Culture (Figure 10).

In a 2020 New York Times piece titled “‘White Fragility’ Is Everywhere. But Does Antiracism Training Work?,” Daniel Bergner describes his conversations with proponents of Katz-like frameworks such as Glenn Singleton, who runs a DEI firm, Courageous Conversation. Bergner asked Singleton if putting “less value, in the classroom, on capacities like written communication and linear thinking” might harm black students’ chances for success in life. Singleton replied: “If you hold that white people are always going to be in charge of everything, then that makes sense.” In other words, in Singleton’s view, if black people are forced to find success in a “white” world that values “white” cultural norms like written communication and linear thinking, then black students must, sadly, be taught to write and to think linearly. But Singleton envisions a future world without whiteness, “a new world, a world, first and foremost, where we have elevated the consciousness,” and presumably no longer need written communication and linear thinking but only “love.”

To teach this framework is, at the end of the day, to tell educators and children—and specifically to target the message to and about black children—that self-reliance, working hard, politeness, thinking objectively, taking an interest in the written word, delaying gratification, planning for the future, and being an individual are “white” or “white supremacist.” One has to ask just how personally empowering and motivating this message might be for black children. And one has to ask what effect this message about black children might produce in educators. How much positive reinforcement will a teacher committed to the message of Okun or Katz give to a black student who loves Computer Science, a field that utilizes “objective, rational linear thinking”? Will such a teacher hold a black student who has been shirking her writing assignments to a high standard? Or will that teacher decline to do so, chalking her disinterest in the written word up to her “blackness”?

Two things seem clear. First, no teacher who deeply internalizes this framework will truly expect their black students to go on to discover a new solar system, engineer more efficient electric cars, write the next great American novel, or ascend to the Supreme Court. Second, few “non-white” parents will welcome the Okun-Katz message. Try it out on an Indian-descended, Korean-descended, Hispanic, or black parent and see for yourself.

3. Segregating children by race or ethnicity in “affinity groups”

In DEI ideology the essence of “blackness” is victimhood and oppression and the essence of “whiteness” is privilege and oppressiveness. One practical result of these essentialisms has been the reintroduction of segregation in school. (A similar movement is happening in medicine.) If black children and white children are essentially different, and if the latter are potentially oppressive to the former, then separate spaces follow as a natural way to protect black children and other children of color from their white peers and from “whiteness” itself.

This “safe space” rationale is spelled out in an invitation to a “Healing Space” for “Asian and Asian American students and others in the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) community” sent by Wellesley Public Schools in Wellesley, MA (Figure 11). The invitation carefully specified that white students were not allowed:

“This is a safe space for our Asian/Asian-American and Students of Color, *not* for students who identify only as White.”

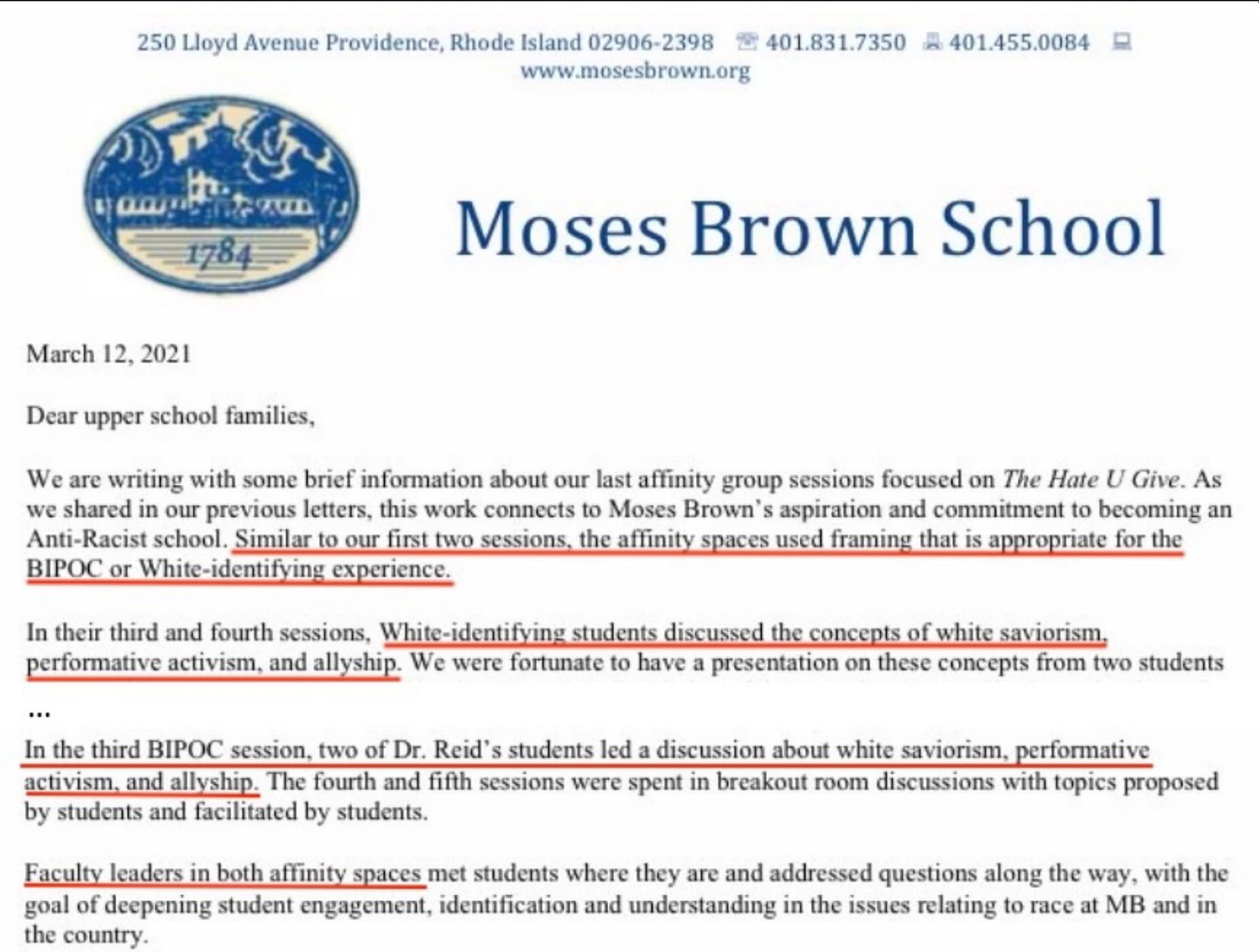

Segregated spaces in Wellesley Public Schools followed an anti-Asian incident, but other schools have taken to segregating students during the normal school day, such as Moses Brown School in Providence, RI. Administrators sent parents of its high school students a letter (Figure 12) detailing how children were split up into two “affinity spaces,” one for “White-identifying” (original capital W) students and one for “BIPOC,” or “Black, Indigenous, and People of Color,” students. The spaces featured different lessons, or in the words of the school, “framing…appropriate to the BIPOC or White-identifying experience.” These “framings” covered popular topics in DEI ideology: “white saviorism” (no capital W this time), “performative activism,” and “allyship.” Separate but, one must presume, equal, in the eyes of the school.

A few years earlier, the Bank Street School for Children in New York City had done something similar (Figure 13). It established a “KOC Affinity Group” for “Kids of Color” and an “Advocacy Group” for white students, in which children were encouraged to develop “awareness of the prevalence of Whiteness and privilege” and taught to “understand and own European ancestry and see the tie to privilege.”

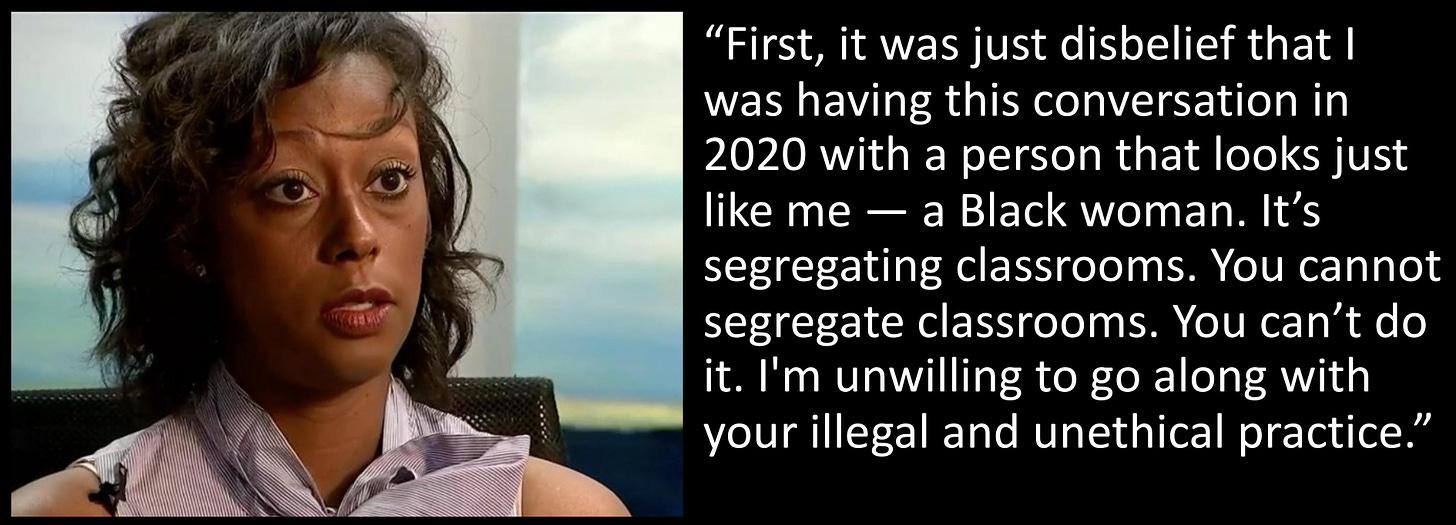

When a similar practice was instituted in the second grade at Mary Lin Elementary School in Atlanta in 2020, Kila Posey, a black parent, PTA member, and educator, filed a federal discrimination complaint alleging civil rights violations with the U.S. Department of Education. Ms. Posey describes her initial conversations about her daughter’s segregation with Principal Sharyn Briscoe, who is also black (Figure 14):

If segregating students by race potentially violates Civil Rights law, as Ms. Posey alleges, there’s also not much reason to believe that it has any pedagogical or other value. There has been little to no serious empirical evaluation of the supposed benefits of affinity spaces. As Rick Hess, a Senior Fellow and Director of Education Policy Studies at AEI puts it, “the supposed evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of racial affinity spaces is nowhere to be found.”

What we can say for sure is that affinity spaces treat children of different races differently. This is exactly what such spaces are designed to do. As Paul Rossi, the former math teacher at Grace Church High School, put it, DEI “requires teachers like myself to treat students differently on the basis of race,” which is just racism itself.

What could go wrong with segregating students by race and treating them differently based on crude, de-individuating stereotypes about what “the BIPOC experience” is like? One possibility is that the entire framing that underlies mandatory affinity spaces actually reinforces racial hierarchies, when the whole point should be to overcome them. For, as we have seen, in these spaces “white” students are supposed to learn about their “privilege” and about how to be “advocates” or “allies,” while non-white students are supposed to learn about their shared disadvantages. The trouble is that “advocates” and “allies” are not peers to those for whom they advocate or with whom they are allied. DEI does not envision collaboration among equals across racial lines.

Might not the experience of being separated, racialized, and then treated differently based on that racialization foster in children a mutual distrust, create a sense of racial exclusivity, and decrease any sense of larger, shared identity? Our democracy presupposes—and Civil Rights victories were won because of—coalitions of diverse people identifying as Americans and standing as equals in solidarity for shared goals. Can our children stand together in this way while also standing apart in their “affinity spaces”?

Figure 15 presents Gordon Allport’s “Intergroup Contact Theory,” a constructive alternative to neo-segregation, in which diverse people cooperate as equals to realize a common goal. It turns out that collaborating as equal partners in a shared enterprise reduces prejudicial attitudes and “leads to the perception of common humanity.” As Allport put it in his 1954 book, The Nature of Prejudice:

“Prejudice…may be reduced by equal status contact between majority and minority groups in the pursuit of common goals. The effect is greatly enhanced if this contact is sanctioned by institutional supports (i.e., by law, custom, or local atmosphere), and provided it is of a sort that leads to the perception of common interests and common humanity between members of the two groups.”

We would propose that this well-tested method is a promising alternative to segregating children and subjecting them to divergent curricula based on their race. Further suggested alternatives to traditional DEI follow in the coda to this article.

4. Constructive/Inclusive vs. Critical/Liberated Ethnic Studies

A K-12 phenomenon that is sometimes DEI-adjacent is Ethnic Studies. It comes in two broad varieties, Constructive (or Inclusive) and Critical (or Liberated). Constructive Ethnic Studies is broadly “multicultural.” It emphasizes understanding other cultures, respecting the contributions and accomplishments of different ethnic groups, and grappling with multiple perspectives. A representative book advocating the Constructive approach is James A. Banks’s Teaching Strategies for Ethnic Studies. The Constructive model of Ethnic Studies is non-partisan and focused on expanding your child’s appreciation of the rich cultural tapestry that is America.

Critical Ethnic Studies is more narrowly political and more properly “DEI.” It emphasizes the oppressed vs. oppressor framing and seeks to “challenge imperialist/colonial hegemonic beliefs and practices on ideological, institutional, interpersonal, and internalized levels.” It advocates militant resistance as a means to social change. For example, Education at War, edited by A. I. Ali and T. L. Buenavista, announces that “concerted efforts and collectivized resistance to US imperialism ground our approaches for dismantling the (neo)colonial schooling apparatus.” Another representative book advocating the Critical approach is Rethinking Ethnic Studies, edited by R. Tolteka Cuauhtin, et al.

Figure 16, borrowed from our friends at Alliance for Constructive Ethnic Studies, presents a chart comparing the two approaches.

In 2021, California passed a bill (AB-101) mandating Ethnic Studies as a high school graduation requirement and the state adopted a non-mandatory “Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum,” or ESMC, for K-12 schools. The ESMC went through several contentious drafts and revisions. The first draft received scathing criticism. The LA Times editorial board called it “an impenetrable melange of academic jargon and politically correct pronouncements,” and said that the ESMC “curriculum feels like it is more about imposing predigested political views on students than about widening their perspectives.”

More damningly, Dr. Clarence Jones—a close associate of MLK and currently Visiting Professor at the University of San Francisco—wrote to Gov. Newsom and Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond to condemn the ESMC and defend the Civil Rights movement in which he had played a key part. Among the ESMC’s omissions: its list of 154 “Important Historical Figures Among People of Color” did not so much as mention Martin Luther King, Jr., or John Lewis (or, for that matter, Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, or Thurgood Marshall, among others).

We often hear that using Critical Race Theory (CRT) in K-12 is “just teaching history,” but according to Dr. Jones, the second draft of the CRT-influenced ESMC was a “perversion of history” and a “reprehensible falsification of historical fact” for its presentation, or rather non-presentation, of the Civil Rights movement (see Figure 17):

“It is a fact that the Black Freedom Movement of the 1950s and 1960s under Dr. King’s leadership transformed our country, overthrowing a century of Jim Crow segregation and white supremacist terror throughout the former Confederate states.

This fact, which I had thought was well known to all educated persons, has been removed from the ESMC.”

The final, approved draft of the ESMC is better than earlier ones but still marked by “Critical/Liberated” elements. Fortunately, it is not mandatory but, as the name states, only a model. Unfortunately, however, there is a group of academics, the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium (LESMCC), that is promoting an iteration of the original, rejected ESMC. This group is composed of the original writers of the ESMC, who were dismissed after their initial draft was roundly rejected. However, one by one, districts are falling prey to LESMCC's efforts to paint themselves as the "true Ethnic Studies" and are hiring the group. In fact, LESMCC has devised a national strategy (launched in February, 2022) to promote their curriculum in various states.

Responding to LESMCC’s efforts, Bill Honig, former California Superintendent of Public Instruction and current Vice-Chair of the California Instructional Quality Commission, recently recommended the Constructive approach and warned:

“Liberated ethnic studies proponents sideline racial progress and focus on immutable differences. Some dismiss individual merit, tolerance, the rule of law and compromise through reasoned discussion—values that prevent anarchy and authoritarian rule—as simply ways to maintain privilege. Most distressingly, liberationists’ emphasis on victimization narrows students’ perspectives and deprives students of the agency they need to reach their fullest potential.”

Fortunately, Constructive curricula have long been available and new ones are being produced and made freely available, such as the FAIRstory Curriculum produced by the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR). The FAIRstory Curriculum:

“exposes students to the histories, experiences, struggles, accomplishments, and contributions of Americans of diverse backgrounds. Ours is a fact-based approach to teaching students about racism; it’s honest about the failures and shortcomings of our American past and present while recognizing how the struggles and accomplishments of Americans continue to move us closer to our ideals. Students learn to counter racism and intolerance with humanity and compassion.”

Parents and educators who believe schools should teach academic disciplines in a non-partisan way rather than indoctrinate children into fringe ideologies have multiple excellent options.

5. Lowering/eliminating standards in math education

Another hallmark of DEI is the lowering or eliminating of standards in order to achieve “equity.” This element of DEI is clearly on display in a list of demands drawn up by faculty at Dalton School in Manhattan in 2020:

“Commit to racial equity in leveled courses by 2023; at that time, if membership and performance of Black students are not at parity with non-Black students, leveled courses should be abolished.” [Note: “leveled courses” are equivalent to Advanced Placement, or AP, courses.]

If black students are not getting into AP courses, don’t do what’s needed to foster their academic development: just ditch the courses.

Similar concerns about equity drove the University of California and the California State University systems to drop the SAT and ACT as admissions requirements. They did this despite the detailed report of a faculty task force which stated that it “did not find evidence that UC’s use of test scores played a major role in worsening the effects of disparities already present among applicants.” The fact is, as Freddie DeBoer writes, “The SATs don’t create inequality. They reveal inequality.” (More on this by DeBoer here and here.) To think we can eliminate inequality by eliminating measurements of inequality is foolish, a disservice to children, and self-destructive for our country. Instead, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that all children have the opportunity to attain the full development of their human potential.

Here are three more examples of this phenomenon from K-12, exemplified in math “detracking.” Detracking is the practice of eliminating more- and less-advanced math classes for students at different levels of proficiency and placing all students, regardless of proficiency, in the same class. The idea is that tracking perpetuates inequalities by disproportionately corralling students from marginalized communities into lower-level classes while advancing already well-resourced students into “smart kid” classes.

San Francisco Public Schools’s math “detracking” experiment, 2015-present.

San Francisco “eliminated accelerated middle and high school math classes, including the option for advanced students to take Algebra I in eighth grade.” An analysis of the detracking experiment by a skeptical parents’ group, Families for San Francisco, found that “overall test scores are down and…the new math sequence created a new set of inequities.”

Princeton Public Schools considers math detracking.

Princeton Public Schools paid $92K to a consulting group, Performance Fact, to advise them that “equity demands ‘equal outcomes, w/o exception’ for every student.” They paid a detracking consultant, Dr. Eric Milou, $47K to recommend dropping 7th-8th grade Algebra, ending math at Precalculus, and getting rid of Calculus entirely. Then they lied about it to concerned parents. Parents pointed out that the school’s new “extreme and simplistic approach to equity leads naturally to the district’s new ‘leveling down’ approach” and worried that “disadvantaged students…stand to lose the most.” The program was abandoned due to parental outcry.

California Math Framework: a model for detracking.

The California Math Framework, or CMF, with its extensive program of math detracking and math elimination, is the inspiration for Princeton Public Schools’ abortive foray into detracking. Chapter 9 of the CMF makes the promising claim that “the goals of equity and of high mathematics achievement are not in tension.” However, Brian Conrad, Professor of Mathematics at Stanford University, and one of the CMF’s most formidable critics, finds that the CMF fails to achieve the goals of either “equity” or “high mathematics.” His assessment is devastating:

“Those who claim to be champions of equity should put more effort and resources into helping all students to achieve real success in learning mathematics, rather than using illegal artificial barriers, misrepresented data and citations, or fake validations to create false optics of success.”

“Whatever author is responsible for such a myopic view of mathematics should never again be involved in the setting of public policy guidance on math education.”

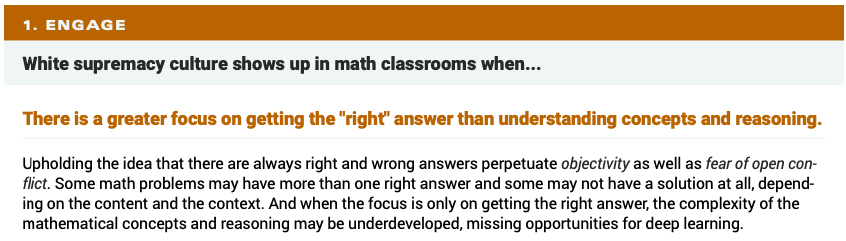

Some DEI practitioners employ the “white supremacy culture” framing (see section 2 above) to alter or eliminate time-tested methods of teaching math. This way of thinking about math education suplements detracking (“White supremacy culture shows up in math classrooms when...Students are tracked”) with Tema Okun’s theory of white supremacy culture, which we discussed above.

The fundamental idea, as John McWhorter summarizes it, is that “math as we have always known it is racism.” The key text for this approach is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-funded A Pathway to Equitable Math Instruction: Dismantling Racism in Mathematics Instruction, which puts it thus:

“The framework for deconstructing racism in mathematics offers essential characteristics of antiracist math educators and critical approaches to dismantling white supremacy in math classrooms by making visible the toxic characteristics of white supremacy culture with respect to math.”

In practical terms, this cashes out as the discarding or demotion of a lot of useful pedagogical methods. For example, “showing your work” reflects white supremacy culture, because it “center’s the teacher’s need to understand rather than student learning.” (Figure 18):

On the contrary, as Jerry Coyne, Professor of Biology at the University of Chicago, notes:

“As you’ll know if you’ve either learned or taught math, showing your work is essential in correcting errors of thinking and demonstrating how you solved a problem. But your implicit bias is showing, for that idea clearly evinces anti-black racism.”

Note: In the latest version of the passage about “showing work” (available at the links in this article), the writers have excised references to Okun’s worship of the written word and paternalism (visible in Figure 18), and have inserted an injunction to “focus on students showing their work in ways that help students learn.” Perhaps this was in response to criticism. If so, it’s a step in the right direction and shows that potentially harmful DEI practices can be changed through pushback.

Other manifestations of white supremacy culture in math include a preference for “procedural fluency” over “conceptual knowledge” and “getting the ‘right’ answer” (Figure 19). Supposedly, these are “white” cultural values, particularly that of objectivity, a sin familiar from Tema Okun’s work.

Surely getting the right answer is important as often as not and surely math instruction needs to involve the imparting of procedures. Indeed, it is often the case that conceptual understanding results from procedural doing. Moreover, as John McWhorter points out:

“to value ‘procedural fluency’ — i.e., knowing how to do the fractions, long division … — over ‘conceptual knowledge’ is racist. That is, black kids are brilliant to know what math is trying to do, to know ‘what it’s all about,’ rather than to actually do the math, just as many of us read about what physics or astrophysics accomplishes without ever intending to master the math that led to the conclusions.”

Similar approaches to math education—such as the framework used in Seattle public schools, which focuses on such themes as “Power and Oppression”—may be found in many districts. But they are meeting with resistance. We’ve already noted the parental victory over detracking in Princeton, Brian Conrad’s extensive criticisms of the California Math Framework, and the concession made to “showing your work.”

Of special note are the efforts of Jelani Nelson, Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences at UC Berkeley, and Dr. Adrian Mims, Sr., of the Calculus Project. They published a deep critique of the California Math Framework, predicting that the framework will “make it very difficult for students to be able to reach calculus.” And they note that the CMF is informed by interpretations of the available research that are both bad and selective. They conclude that “it is irresponsible to make such radical (and detrimental) recommendations for the education of students in our largest state based on inconclusive or cherry-picked evidence.”

Prof. Nelson and Dr. Mims launched an open letter, signed by over 1700 “professionals in STEM and quantitative fields,” which opens by expressing its authors’ and signatories’ “alarm over recent trends in K-12 mathematics education in the United States” (See Figure 20).

The open letter concludes by warning against “reducing access to advanced mathematics and elevating trendy but shallow courses over foundational skills”—exactly the sort of curricula we saw in the white supremacy-obsessed Dismantling Racism in Mathematics Instruction and in the CMF—because the adoption of these curricula “would cause lasting damage to STEM education in the country and exacerbate inequality by diminishing access to the skills needed for social mobility.”

6. Misrepresentation of “Implicit Bias”

The concept of “implicit bias” is the backbone of the $ billion DEI industry. It’s claimed to be the cause of disparities great and small. As a result, practices designed to eliminate or neutralize it are central features of just about every DEI program, whether at the corporate, K-12, or college level. It’s conceivable that without implicit bias, DEI would cease to exist, at least in its current form.

As it turns out, implicit bias is not what the DEI regime says it is. DEI badly misrepresents and misuses the concept. Unfortunately, most of us derive our (mis)understanding of implicit bias from the DEI industry itself, which is, ironically, a biased source.

Let’s look at an example. This is how the Pollyanna Racial Literacy Curriculum represents implicit bias in its seventh-grade curriculum (Figure 21):

“implicit forms of bias — even if ‘unknown’ — still have an impact on our lives, as they regularly manifest into acts that often provide either social advantages or social disadvantages to others.”

The important—and misleading—feature of this definition to note is the idea that our implicit biases “regularly manifest into acts” that perpetuate social inequalities. This is simply not what the science says.

Lee Jussim, Professor of Psychology at Rutgers, describes the scientific standing of implicit bias. First, “there is no consensually-accepted scientific definition of implicit bias.” The field is rife with idiosyncratic and mutually contradictory working definitions. Scientists have yet to agree on what they are even talking about. Second, “most of the most dramatic claims about [the Implicit Association Test, or IAT, which purports to measure implicit bias] have been debunked or, at least, shown to be dubious and scientifically controversial.” Thus the test for implicit bias, and the implicit bias it claims to be testing, are not scientifically well-established enough to provide the foundation for an entire industry. Finally, perhaps most surprisingly, and yet certainly the best news of all, “many of the studies that use IAT scores [of implicit bias] to predict behavior find little or no anti-Black discrimination specifically.” Indeed, an important meta-analysis of studies looking for relationships between implicit bias and discriminatory behavior found that “IATs were poor predictors of every criterion category other than brain activity.” (Listen, too, to the thorough discussion of studies of implicit bias on this podcast). Perhaps the solutions to the social inequalities that we care about are not to be found in obsessing over our implicit biases.

Let us leave the last word summing up the state of the science on implicit bias to Musa al-Gharbi, Paul F. Lazarsfeld Fellow in Sociology at Columbia University:

“Implicit attitudes are one of the most commonly relied-upon constructs in contemporary diversity-related training. However, there are severe problems with these constructs—as hammered home by meta-analysis after meta-analysis: it is not clear precisely what is being measured on implicit attitude tests; implicit attitudes do not effectively predict actual discriminatory behavior; most interventions to attempt to change implicit attitudes are ineffective (effects, when present, tend to be small and fleeting).

Moreover, there is no evidence that changing implicit attitudes has any significant, let alone durable, impact on reducing biased or discriminatory behaviors. In fact, to the extent that discriminatory behaviors are attributed to implicit biases, people often view them to be outside of one’s control—and therefore, view it as unjust to hold people accountable for said behaviors. Implicit bias training can even lead to reduced concern about bias, and adopt a fatalistic approach about it, due to the perception inculcated in training that bias is ubiquitous and not something people from high-status groups can actually rise above.

In short, the construct itself has numerous validity issues. Training to combat implicit bias has no demonstrable benefit—and may be even be counterproductive with respect to changing behaviors.”

Thus, the foundation of DEI ideology and the DEI industry—implicit bias—is sand. There is a great deal at stake in taking this fact to heart. In the course of dismantling another disreputable DEI concept, the “microaggression,” Musa al-Gharbi warned about “the long and ignoble history of harm caused by hastily applied (and often later discredited) social and psychological research—with the costs borne primarily by women, people of color, the poor and other vulnerable populations.” Implicit bias is precisely one of these “hastily applied” artifacts of social and psychological research. Let’s walk away from implicit bias before it and the DEI industry that rests upon it contribute to that “long and ignoble history of harm” by damaging our children.

Coda: For what may we hope? Alternatives to DEI

We have seen that the DEI industry in K-12 schools, whatever benefits it may provide, has the potential to disserve our children. (For deeper dives into DEI than this article can offer, see these books, here, here, here, and here.) This does not mean that we should simply throw up our hands. Although overt racism and other forms of bigotry have declined precipitously in the last 50-to-70 years, it is still true that some children, underdeveloped human beings that they are, and even some teachers or school staff, will inevitably at some point bully, humiliate, insult, to subject to unintentional slights someone else, in ways that are racist, sexist, homophobic, and so on. Presumably, people of good will recognize this and accept that it would be good to have some means of producing ever more harmonious, increasingly less fraught social interactions that conduce to more intimate individual collaborations, ever deeper social cohesion, and ever greater human fulfillment all around.

Fortunately, people of good will have at their disposal a lot of alternatives to DEI. The journalist Matt Yglesias has outlined a few of them here and Musa al-Gharbi has discussed others here. We run through a few that we especially like for K-12, below.

We remarked, in section 3, upon the well-supported framework of “Intergroup Contact Theory,” deriving from the work of Gordon Allport. The evidence suggests that it can be used as an entirely positive alternative form of DEI in schools.

We’ve also mentioned FAIR, the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism. FAIR pursues a “mission of advancing civil rights and liberties for all Americans, and promoting a common culture based on fairness, understanding, and humanity.” They have a variety of programs for K-12, including an alternative DEI FAIR Schools program that offers “training, standards, and curricula that uphold FAIR’s pro-human values.”

Moral Courage is another promising alternative. Driven by the conviction that children and adults “need the skills to hear, not fear, different perspectives,” it fosters “constructive conversations” about even the most difficult topics. Its founder, Irshad Manji, has written a book, Don’t Label Me: An Incredible Conversation for Divided Times, that elaborates upon the underlying ideas.

Also worthy of attention is Constructive Dialogue Institute, which offers resources for teachers, administrators, and high school students designed to “help students build a foundational mindset and skill set to learn, communicate, and thrive in a diverse world” with the goal to “improve classroom climate, foster belonging, and facilitate constructive dialogue in your classrooms.”

Of special note is The Mill Center, a partner organization of FBT. The Mill Center “works in educational settings to teach the skills needed to inspire intellectual risk-taking, expand empathy, and deepen conversations.” They offer resources that help “turn down the heat on controversial topics so educators and students can untangle complex issues together” and they “teach the mindset, skills, and ground rules needed to broaden conversations and expand knowledge.”

EmpowerED Pathways, a project of FBT co-founder Jason Littlefield, offers “a brain and humanity-based approach to life, leadership, and learning” that “recognizes the brain continues to grow and change throughout a lifetime.” EmpowerED Pathways strives to “leverage the K-12 (and beyond) experience to cultivate the neural pathways of resilience, compassion, and understanding.” It does this through consulting and training based on “Empowered Humanity Theory,” which cultivates students’ “most benevolent qualities, motivations, and traits.”

Finally, one of the most worrisome elements of DEI ideology, as we see it, is the way it functions both to essentialize race (while insisting that race is mere “construct”) and to insist that supposed racial differences insuperably divide some people while uniting others in exclusionary communities of interest. Some of us (not all) at Free Black Thought are persuaded that race is not real and that what we imagine to be race is in fact what makes racism possible. Thus, racism can only be defeated if we overcome our belief that there is such a thing as race that differentiates us. If this approach interests you, we highly recommend Theory of Racelessness, or TOR, developed by friend of FBT Sheena Mason. TOR is “a nonpartisan unity, healing, and reconciliation educational firm” that offers consulting and training to help students and educators “deeply consider the history of both racism and the impact of ‘race’ and race concepts today” in such a way as to overcome “alienation and misidentification” and discover the deeper aspects of themselves that they share.

We at FBT are confident that a better world is possible. We are also quite certain that the existing DEI industry does not have the practical or conceptual resources to help us create it. We hope that the alternatives to DEI that we’ve presented here inspire you. We truly believe that we can heal the wounds inflicted on our society by bigotry past and present, so long as we focus on and affirm what we all share as Americans and as human beings, created equal. Our children are depending on us to do so.

The editors thank Elina Kaplan, Lee Jussim, and Paul Rossi for constructive comments and/or further references that enriched this article. All mistakes are, needless to say, our own.

The sad thing is children have to be taught to see race. They might notice that their friend looks different from them, but they won't weigh skin color any more than they weigh hair color or eye color. In fact, they won't think anything much of it at all until the adults in their lives teach them to see that friend as BEING different.

I do not mean to imply any sort of moral equivalency here, just to note a commonality, but that being said:

The modern Identity-obsessed Left has set up a system of totalizing racial classification that I don't think I've seen anywhere since the antebellum/Jim Crow South.

If you read about the South in those times a person's race was the most important thing about them, and you needed to know their race before you could decide what they were allowed to say or do, what was their social and moral value, where they were allowed to live and who they were allowed to date, which schools they went to, and this was on top of classifications by blood: the one-drop rule, octoroons and quadroons, etc.

Now of course I'd prefer to live in a society dedicated to antiracism rather than its opposite, but both societies/ideologies make it impossible to get past the idea of racial categories and racial divisions, both foment division and suspicion, and both deny the idea of a human as individual and not defined by their race. And both slap a racial label on every aspect of existence and then add a moral judgment, whereby your race makes you inherently Good or Bad depending upon the ideological lens applied.

And both also have this last commonality: the people most dedicated to racial classification and racial policing claim higher social and moral motives, but really use race as a way to divide and conquer, as a way to accrue power and set people against each other for their personal benefit.

"The racialization of the world has to be the most unexpected result of the anti-discrimination battle of the last half-century. It has ensured that the battle continuously recreates the curse from which it is trying to break free." — Pascal Bruckner